Reading through the RFPs for the southern border wall, one notices immediately that the thrust of the documents is outward. These documents outline a not-yet-extant prototype, which itself is merely a suggestion of further border infrastructure. This imagined border infrastructure only carries weight through political context, and perhaps for that reason, architectural reporting on the border wall has been largely documentary rather than analytical. It has avoided identifying underlying motivations for the RFPs or suggesting professional reform to address the topic. Tackling the RFPs requires not only parsing the documents but also their proposed effects—not only in the form of prototypes but also the effects on its target audience. Although the history of the border wall stretches centuries, this review limits its scope to the immediate political context and identifies the way the architectural profession has entered into that discourse.

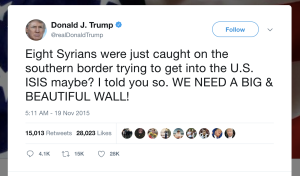

The present iteration of the United States / Mexico border infrastructure began publicly developing on Trump’s twitter feed during the Obama administration. In the years before his presidency, Trump had been increasingly tweeting about border security, and in 2016 he incorporated the construction of a southern border wall into his campaign platform. The general premise put forth in the announcement of his bid for candidacy was brief: to build a great and inexpensive wall, and to have Mexico foot the bill. Although shortly after the election Mexican president Enrique Pena Nieto stated, in no uncertain terms, that Mexico would not fund the border wall, the campaign promise was put into motion on March 17, 2017, in the form of two request for proposals (RFPs) concurrently issued and announced in a press release by the US Customs and Border Protection agency (CBP). The first RFP outlines the specifications for a solid concrete border wall, while the second outlines the specifications for material alternatives to a concrete border wall. Other than differentiated materials, the two RFPs share the same fulfillment requirements. The characteristics of compliant bids include a physically imposing stature, deterrence of various forms of breach, an accommodation of surface drainage, and that the northern-facing (US-visible) side of the wall be aesthetically pleasing (no such consideration is made for the southern-facing side). Although each RFP comes in at 132 pages, the broader purpose of the southern border wall is never explicitly stated and is only implied through these fulfillment requirements.

The contracts to build prototypes were announced on August 31, 2018, with none awarded to architects. Instead, six contractors (WG Yates & Sons, ELTA North America, Caddell Construction, Texas Sterling Construction, KWR Construction, and Fisher Sand & Gravel) were chosen to build the prototypes. An investigation into the awarded bidders reveals that each company has construction experience in typical government work (embassies, highway infrastructure, etcetera), with the exception of ELTA North America, which performs work in the aerospace and defense sectors and specializes in surveillance technology. As a subsidiary of Israel Aerospace Industries, Inc., they are also the only company not headquartered in the United States.

Construction of the prototypes took place shortly after the contracts were announced, from September through October 2017, and to accelerate construction, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) exempted the project from compliance with any environmental regulation. Despite the requirements in the RFPs, only two of the prototypes address surface drainage and none of them accommodate the migratory patterns of terrestrial animals and insects. Although $1.6 billion of the latest Congressional budget has been allocated to constructing the border wall, it explicitly limits the spending to designs that have already been implemented.

To understand Trump’s RFPs and the artifacts produced, they cannot be taken at face value as documents that outline the requirements for the fulfillment of a contract; they need to be addressed as a political tool deployed in a historical context of border infrastructure—a context in which any responding practice participates. The latest iteration of the border wall has its roots in Operation Gatekeeper, a policy implemented under the Clinton administration that grew the CBP budget and began lengthening the border wall. The southern border wall was further reinforced and funded through the 2006 Secure Fence Act under the Bush presidency. These practices continued through the Obama presidency and are now a present issue. The border wall currently in place takes on a variety of forms along its length, from recycled Vietnam-era helipads and reinforced steel tube to natural barriers and simple barbed wire. The selected prototypes resulting from these RFPs are intended to replace much of the existing border wall and, if the current administration is to be believed, replicated along the full length of the border.

The apparent function of these prototypes is straightforward: to prevent individuals from entering US territory on land by way of Mexico outside of a sanctioned checkpoint. While the existing border wall may deter immigrants from crossing on foot, a large number of immigrants come to the United States through legal channels and overstay their visas as their situations require, or they are smuggled across the border. It is unlikely that these prototypes would do anything more than inconvenience those interested in making the crossing in unorthodox or creative ways. Even in interviews, employees of the CBP have expressed doubts about whether a border wall would be effective.

If the requirements laid out in the RFPs would only marginally address the larger discussion around how the border is crossed, it begs the question as to why the US government has entertained this exercise. For the current administration, the prototypes created via these RFPs are useful, even if unimplemented, as a propagandistic set piece. The construction of the prototypes entails a security theater on both sides of the border. To the north the CBP is able to dissuade protest or dissidence as an echo of Trump’s threats toward news media, and to the south the prototypes project a visual display of force to Mexican citizens, at least as perceived by supporters of a strengthened border. Trump’s chest-puffing rhetoric alongside imagery of the prototypes serves to gather a political base of profascist conservatives around the marginalization of minority populations while normalizing spatial oppression to the American public. The broader achievement of these RFPs, though, is the call for further militarization of infrastructure by providing a platform for surveillance technology to be deployed. The aforementioned failures of the physical border wall provide a market for defense contractors to hawk their wares as problem-solving tools to the US government. Evidence of the effects of militarized infrastructure can be seen in many places, recently in the well-publicized use of juvenile detention centers along the border to imprison children who have been separated from their families by the CBP while attempting to cross the border. Political maneuvers such as these reset the high-water mark for intolerance and provide cover for more mundane acts of marginalization and abuse to go unnoticed.

The reaction by the architectural profession to this process can be summarized by American Institute of Architects (AIA) president Robert Ivy’s statement to its membership shortly after Trump’s election, stating, “The AIA and its 89,000 members are committed to working with President-elect Trump to address the issues our country faces, particularly strengthening the nation’s aging infrastructure.” Ivy later apologized for the tone-deafness of the statement, but not for the underlying message: that Trump’s investment in infrastructure represents a potential economic opportunity. This continues the stance the AIA took in 2014 against the Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility’s (ADPSR) proposed rule on ending the design of spaces for torture, execution, degrading treatment, and solitary confinement by insisting that the AIA Code of Ethics is only relevant for issues of practice and “should not exist to create limitations on the practice by AIA members of specific building types.” The implicit content of this stance is that in providing a venue for atrocities to take place, architects bear no moral responsibility. While firms across the United States submitted proposals hoping for the opportunity to land a large government contract, other architects viewed the RFP as an opportunity to produce marketing material for their practices through imagery of either humane or whimsical border wall proposals. It is worth noting that these utopian visions are still visions of border infrastructure, which as recently as thirty years ago was only obelisk-shaped monuments and cattle fences. Among the organizations to explicitly come out against participating in the construction of the southern border wall were The Architecture Lobby (TAL) and ADPSR. The latter issued a five-point statement on the RFPs as damaging to human rights, diplomacy, ecology, and border communities as well as economically wasteful. The statement concluded with a call for protest proposals to be submitted to the DHS. Similarly, TAL organized walkouts at architecture offices across the United States and encouraged its membership to speak to their firms about the project and to deny their labor toward the project should the office decide to answer either RFP. In addition, members of TAL documented the distribution of the RFPs and the construction of the prototypes in conjunction with Tijuana-based activists through the publication of #NotOurWall.

Ultimately the exclusion of architects from this project points to a larger failure of the profession—that architects lack influence over infrastructure in the United States. Despite both participation and refusal from architects, the RFPs went to businesses that equate imperialism with economic opportunity. If the AIA’s various pledges for a more equitable society are to be taken seriously, and if architects are truly expected “to protect the health, safety and welfare of the public,” architects need to engage in a political fight to demand oversight on infrastructure projects. Speaking out is a start, but it doesn’t enable us to steer infrastructural investment toward housing, hospitals, schools, and other beneficial typologies. If granted oversight on projects such as the southern border wall, architects could deny their labor to great effect, either derailing or terminating the project through protest. To get to that point, however, the profession needs to collectively possess the architectural imagination for a utopia not with a more beautiful, humane, or profitable border infrastructure, but one where it does not exist at all.

James Heard is a worker-owner and architect at uxo architects (@uxoarchitects), a worker-owned California corporation that explores alternative modes of professional practice through the design of spaces for leisure and labor. As a member of The Architecture Lobby, James has helped organize the Los Angeles Chapter, participated in the #NotOurWall and Socializing Small Firms campaigns, and advocated for the value of architectural labor. James currently divides his time between Cambridge, Los Angeles, and Oakland.

How to Cite this Article: Heard, James. “US Customs and Border Protection Agency: Requests for Proposals – The Southern Border Wall (HSBP1017R0022 Solid Concrete Wall Prototype; HSBP1017R0023 Other Border Wall Prototype).” JAE Online. November 27, 2018. http://www.jaeonline.org/articles/reviews-artifacts/us-customs-and-border-protection-agency#/.