OPINION

Biennale Architettura 2023

The Laboratory Of The Future

May 20 – November 26, 2023

Venice Giardini/Arsenale

Lesley Lokko, Curator

Boundary, or the Possibility of Encounter

What is a hard line?

Three Ghanaian men, members of Lesley Lokko’s curatorial team in Accra, were denied visas to enter Italy and take part in the momentous occasion of the International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale. They were served a template of rejection behind the routinized and racialized juridical mechanism of border policy and control. The rejection letter, recited by Lesley Lokko at the opening press conference, stated “there are reasonable doubts as to your intention to leave the territory of the Member State before the expiry of your visa.”1 And upon further public inquiry as to the reasonability of State doubt, the official response from the Italian ambassador to Ghana followed:

A hard line is the ontogenetic plinth on which boundary conditions manifest their rough edges. A hard line conditions and suppresses a dreaded desire for an unknown entanglement—a forecast of Otherness that must remain an eminently peripheral engagement. Boundaries, within the domain of architectural disciplinarity and exhibitionary praxis, often retrofit a Eurocentric architectural, aesthetic, and therefore epistemic core thought to be natural, neutral, and nonnegotiable.3 A border seeks the illusory fidelity of a conventional frame rather than the diffuse, transgressive heterogeneity of culture and its substantive relationship to architecture as a social technology. A border represents an unwillingness to engage or entertain a relational encounter with another. A retreat to the clinical safety of the disciplinary impulse—a Foucauldian moment revealed again in Mbembe’s necropolitical rendering of borders and opportunity, spectacularly modulated by race. 4

Under the direction of Lesley Lokko, architect, novelist, educator, and founder of the African Futures Institute in Ghana, The Laboratory of the Future adopts the erotic. That is, the diffuse and transgressive expressivity of African and diasporic cultures is given the discursive space to enrich an architectural context exhibiting the possibility of “reciprocal, glorious, and unpredictable exchange” between visitor, participant, and exhibit.5 It is this erotic reciprocity that unfolds across several facets of this exhibition: Dangerous Liaisons’ poetic and empowering affordances, Carnival’s circuit of lectures, round tables, films and performances, Force Majeure’s spotlight on emerging and influential African and diasporic designers and architects, and the Curator’s Special Projects that dissolve borders and orient the architectural discourse toward the kinds of culturally informed, situated experiences most responsive to the conditions of those lived realities most marginal to Venice.

The Laboratory of the Future

“Take forgetfulness, make a plinth, indoctrinate architecture into a conveyor belt system, mass producing monotony, colonized cultural contention…call it, call it, call it a practice…call it a culture of creative conformity.” – Rhael ‘LionHeart’ Cape, Those With Walls for Windows (2023)

More than half of the 89 practitioners included in The Laboratory of the Future facilitated the exchange from Africa or the African diaspora. An equal number of relatively young male and female identified participants came from practices of five or less. Together, their material, conceptual, and political offerings engaged the twin thematics of decolonization and decarbonization while plotting a decentralized path toward the future of architectural relations.

The most rewarding experiences within the exhibit were pedagogical moments that revealed the intimate epistemological affordances of African, diasporic, and Indigenous modes of relating, embodying, and knowing. These moments substantively stimulated discussion concerning communities and their thriving local relations to the natural and built environment. As such, the generative and ongoing conversations that I had with other African and diasporan architects, artists, educators, and individuals who came to support the vision of The Laboratory of the Future was incredibly edifying. The nature of our engagements in Venice presented a wonderful set of both opportunities and critiques for the sustainable materialization of our futures in the domain of architectural discourse and its epistemic utility.

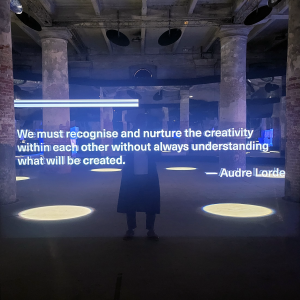

Within the Arsenale’s Corderie structure, Dangerous Liaisons unfolded through a series of poignant quotes that served as a preamble to the exhibition. These introductory exhortations on mirrored surfaces alternated between quotes from James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, and Rem Koolhaas. Resolving and dissolving on terministic screens,6 they iterated the following:

“The world changes according to the way people see it, and if you can alter it, even by a millimeter, the way people look at reality, then you can change it.” – James Baldwin

“We must recognize and nurture the creativity within each other without always understanding what will be created.” – Audre Lorde

“The areas of consensus shift unbelievably fast. The bubbles of certainty are constantly exploding.” – Rem Koolhaas

Figure 1. Image of the author captured in the reflection of quotes on mirrored surface

The “terministic screen,” as a concept, was developed by rhetorician Kenneth Burke to describe the semiotic filters and textures through which humans perceive, interpret, articulate, and ultimately direct attention toward their experiences of the world. If we extend Burke’s notion of terministic screens to account for intersectional conditions, James Baldwin or Audre Lorde’s screens expressed through the lens of radical Blackness and feminism in America are markedly different from Rem Koolhaas’, but Lokko found moments for them to exist here in the strategic framework of a dangerous liaison. As such, these quotes were augmented with Lokko’s own metaphorical reflection on the “rare chromatic beauty” of the vibrant and diverse environmental light captured in the Blue Hour—the resplendent hope filtering in what Lokko refers to as “the moment between dream and awakening.” Their mirrored and media-soaked surfaces circumscribed a dark, vestibular chamber of self-reflection. Just beyond this threshold, multidisciplinary artist and poet Rhael ‘LionHeart’ Cape’s spoken word video performance (“Those With Walls for Windows”) graced the formal entry with an arresting video rendition of an architectural discipline that has sought refuge in the hermetic coffers of its self-produced, Eurocentric image. These introductory moments activated a ritualized space that prepared visitors to view architecture through the eyes and experiences of those who were previously uninvited, dismissed, or unknown.

Figure 2. A still captured from Rhael ‘Lionheart’ Cape’s spoken word video performance

Sammy Baloji’s film Aequare: The Future that Never Was (Special Mention) was an incisive exploration of the Belgian colonial legacies and scars upon the natural and built environment of the Yangambi agricultural center in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Colonial, architectural, and historical critique is put into discursive correspondence with retrofuturist imaginaries like Olalekan Jeyifous’ (Silver Lion for Promising Young Participant) multimedia installation ACE/AAP in the Force Majeure exhibit at the Central Pavilion. Jeyifous dignifies the material, cultural, and conservation programs of the All-Africa Protoport (AAP—a facilitator of zero-emission boundary-crossing, transatlantic mobility, and cultural reciprocity) and the African Conservation Effort (ACE—a reparative steward of Indigenous lifeways and resources) through the expressive tableau of a counterhistory and productive future imaginary. The large-scale drawings, sculptures, digital media, and video strategically visualized the ecological, collaborative, and ultimately transgressive nature of Black mobilities in fluid cultural exchange. They dematerialized geopolitical, colonial, and socioeconomic boundaries while rematerializing shared Pan-African identities. Ultimately, Jeyifous’ tableaus wonderfully galvanized African and diasporic agential capacity to reimagine and control their histories and futurities with the paradigmatic force of Paul Gilroy’s conceptualization of The Black Atlantic.7

Dangerous Liaisons cultivated other lines of reciprocity with Force Majeure in the Central Pavilion, highlighting significant earth-based installations from Francis Kéré that situationally respond to the sustainable, traditional context of Sahelian architecture in West Africa. Similarly, Mariam Issoufou Kamara’s work with atelier masōmī in Niger presented models, videos, and plans drawn on the exhibit’s walls to dynamize the earth-based building strategies that are being locally produced as culturally significant architectural interventions in the built environment of Niamey, Niger.

Figure 3. Francis Kéré’s demonstration of Sahelian architecture

Back at the Arsenale, in a singular moment, a vertical panel in the linen tapestry of Wolff Architects’ submission for Dangerous Liaisons, entitled Tectonic Shifts (Special Mention), detains me. It was dedicated to South African writer Bessie Head (1937–1986). Under the banner of Emancipatory Spatial Practices, a sensitive and poetic film of the indomitable Bessie Head entitled Summer Flowers—revealing her garden, home, and words, surrounded by the firm’s creative process, blueprints, and current work—wove a poignant architectural thread of an intimacy, dedication, and perseverance bound up in one individual.

Figure 4. A vertical panel in the tapestry of Wolff Architects’ ‘Tectonic Shifts’ dedicated to South African writer Bessie Head

With Intention

Some national pavilions were more successful than others in curating a vision that productively engaged the decolonial and decarbonization thematics of the exhibition. They centered Indigenous futures through earth-based relationality and the mobility of Indigenous architectural knowledge, identity, and expression while uplifting contemporary diasporic communities and habitats.

The British Pavilion, through curators Jayden Ali, Joseph Henry, Meneesha Kellay, and Sumitra Upham, presented a film, Dancing Before the Moon, that rendered moving archival portraits of Afro-Caribbean and Asian diasporas throbbing and thriving in embodied spaces of culture and community. The film resonated deeply with my own experiences of diasporic space in various metropoles, where the expressive force of culture exceeds the home, dynamizing and activating public space. These are spaces where individuals draw on the participatory vitality of family and kinship to build and maintain communities whether in salons or on street corners, but always in the face of the indifference of a necropolitical built environment. Dancing Before the Moon featured a diverse range of scenes, from Jamaican dominoes to spaces of black hair braiding and their economies of care and community, to celebrations of the Sikh New Year, Trinidadian steel pan drum-making, and Black bodies occupying space with a powerful display of their visibility and dignity during anti-police riots in the ‘80s. All were foregrounded by a rhythmic, celebratory steel pan soundtrack. As a diasporan raised by a Ghanaian father and Jamaican mother in places like Accra and South London in the late ‘80s, and Brooklyn and the Bronx in the ‘90s, I felt a strong connection to the representation and experiences portrayed at the British Pavilion that shape my own experiences of cultural space. In the attempt to situate a broader architectural discourse—what Nigerian educator, architect, and curator David Aradeon has always championed by emphasizing architecture as culture 8 —these pavilions revealed ancestral, cultural, and relational frameworks that have always existed. As such, they exceeded the narrow framing of architecture as a captive, semantic object, prodigiously virtualizing or beautifying lived conditions through class defining vehicles of commodification.

Figure 5. A .gif captured from the British Pavilion’s ‘Dancing with the Moon’

The Canadian Pavilion featured the valiant work of the Architects Against Housing Alienation (AAHA) titled Not For Sale! They presented a durable platform that continues the work of serving the needs of those most virulently affected by architecture’s role in housing inequality. AAHA didn’t obfuscate its terms through an uncritical spectacle of plasticity and form, nor through speculative poetics. The exterior of the Canadian pavilion was scaffolded with semi-transparent images of the tent-city pragmatics that are a present reality for many at the margins of housing access.

Figure 6. Exterior view of the Canadian Pavilion

AAHA’s imperatives were clear, rooted in direct action, and articulated as ten demands to end housing alienation and build intentional communities. The demands—regionally catalyzed between activists, architects, and advocates—were guided by Indigenous claims for the return of stolen land, reparations to fund Black-led community land trusts as stewards for affordable housing in Toronto’s Little Jamaica, and a rich paradigm of social accountability to address intersectional effects of architecture’s complicity in racial capitalism. In AAHA’s words, TO END HOUSING ALIENATION IN c\a\n\a\d\a WE DEMAND…

- LAND BACK!

- ON THE LAND HOUSING

- FIRST NATIONS HOME BUILDING LODGES

- REPARATIVE ARCHITECTURE

- A GENTRIFICATION TAX

- SURPLUS PROPERTIES FOR HOUSING

- INTENTIONAL COMMUNITIES FOR UNHOUSED PEOPLE!

- COLLECTIVE OWNERSHIP!

- MUTUAL AID HOUSING!

- AMBIENT ECOSYSTEMS COMMONS!

Figure 7. Poster board inside the Canadian Pavilion demanding reparative architecture for residents of Toronto’s Little Jamaica neighborhood

Sámi architect Joar Nango exhibited Girjegumpi at the Nordic Pavilion, a mobile Sámi architectural library and social space centering Sámi epistemologies concerning the natural and built environment. Importantly, the exhibit was architecturally suggestive of the goahti and laavu—both Sámi seasonal and mobile tent typologies—that highlighted contemporary Sámi technologies of land and home. This form of situated place-making among improvised structures enabled all to experience Sámi design strategies that demonstrate spaces of conciliation, adaptability, and traditional knowledge. Girjegumpi was a site-specific iteration made of reindeer pelts, antlers, and ecologically sourced wood, tree stumps, found objects, and Sami duodji fabrics, incorporating Sami symbolic heritage designs on interior walls. The library, as living archive, included historical and contemporary books on Sami design, craft, and architecture, among other books and Indigenous strategies related to the natural and built environment. In other fora, his installations have iterated different improvised tectonic expressions related to Sámi culture, including a Girjegumpi on a sled-based platform in the Arctic to acknowledge the Indigenous technicities of mobility, improvisation, and place that situate contemporary lived experiences of Sámi people. A similar pedagogical frame was present in Ursula Biemann’s work with the Inga of southwest Columbia. She exhibited the collaborative film Devenir Universidad (Becoming a University), which documented the creation of an Indigenous university. The film foregrounded the epistemological affordances that center the sovereign ecosystem of Indigenous knowledge in active collaboration with the rainforest. The focus here extended beyond the university as an educational ideal or its assemblage of tectonic signatures in the built environment, to establish the generative and durable relationships that teach us how to live sustainably with the natural environments.

Gabriela de Matos’ and Paulo Tavares’ exhibition for the Brazilian Pavilion titled TERRA [EARTH] (Gold Lion winner for Best National Pavilion) foregrounded Afro-Brazilian epistemic frameworks of Candomblé spirituality and the stewardship of Indigenous and Quilombola lands amidst earthen floors and rammed earth benches. A powerful video installation by Ayrson Heráclito demonstrated sacudimento—a cleansing practice of West African origin that exorcizes domestic environments through the brushing of the building envelope with sacred leaves. In the video performance, Casa da Torre (off the coast of Bahia, Brazil) and the Maison des Esclaves (off the coast of Senegal, West Africa)—two linked trafficking sites of the transatlantic slave trade—were ritually and architecturally exorcized. Similar transatlantic resonances were explored in the Dangerous Liaisons exhibition at the Arsenale. Sammy Baloji’s collaboration with Brazilian architect Gloria Cabral and Martinican art historian Cécile Fromont on Debris of History, Matters of Memory, produced an undulating brick tapestry that reflected on the history of the slave trade and colonial extraction. This tapestry was bejeweled in an ornamental debris of historical relations that weaved mining waste, colored glass, and African and Indigenous geometric patterns into a narrative totem of diasporic memory and meaning.

Guests from the Future presented 22 emerging practitioners who were integrated into the exhibition at the Arsenale and Central Pavilion. Notably, Senegalese architect Nzinga Biegueng Mboup and film director Chérif Tall coproduced the BUNT BAN installation, whose collaborative work highlighted the development and production of ecological building materials through Senegalese engineer Doudou Deme’s company Elementerre. Similar to Kéré Architecture, Mboup has been involved in bioclimatic architecture and construction using local materials through her Dakar-based architectural practice, Worofila, which she cofounded with Nicolas Rondet in 2019. Worofila’s focus on the reclamation of traditional earth-based materiality and spatial relationships in contemporary form in the Senegalese context is noteworthy and has enabled productive collaborations with Elementerre. Worofila’s previous work on the centrality of the Wolof compound as the communal link that continues to organize surrounding autonomous dwelling units, along with the resignification of outdoor lived environments, demonstrated culturally responsive strategies that reclaimed socially mediated spaces of local Senegalese cultures. Worofila’s collaboration with Elementerre’s expertise in a variety of laterite soils and earth-based materials, as shown in the film and demonstrated in their built projects, challenges the conventional and colonial appetite for concrete as the primary building material of the African built environment. Elementerre provides innovative access to sustainable biomaterials including raw earth and Typha reeds which help to stabilize their earth-based products. Together, Elementerre and Worofila’s climate-sensitive practice is actively reclaiming, disseminating, and sustaining local industry and knowledge that center African technicities of environment, habitat, and culture rather than imported style.

Acts of Love

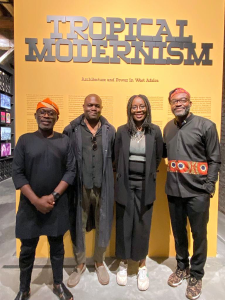

Figure 8. Nigerian architect Adeyemo Shokunbi, the author, Ghanaian-born curator and educator Nana Biamah-Ofosu, and Sierra Leone-born architect Joseph Conteh.

Lesley Lokko invited us to think of the exhibition as a “love letter, a passionate description of the task that lies ahead.” 9 Acts of love facilitate agential capacities that directly produce substantive realities. Instead of exhibiting the commodified expressions of representational abstractions that captivate increasingly passive spectatorship, The Laboratory of the Future, through its ongoing programming of lectures and workshops, enables us to ask: Who is captured in architecture’s grand image? Whom has it ignored? Whose memories are implicated? Who gets to revel in the wide spectrum of architectural relationality and culture? Who are its producers?

I spent my last day at the exhibition revisiting many of the works and pavilions with Dele Adeyemo, one of the invited Guests from the Future. His work, A Dance of Mangroves, was exhibited in the Arsenale and represents some of the ways in which we, as diasporan artists and educators, are trying to situate the material, formal, spiritual, and epistemological affordances of African culture in our architectural pedagogies from various metropoles (he in London, I in Montréal). We talked about Dele’s continued artistic and curatorial efforts as well as my research program and forthcoming book on African Technicities. We embraced the moment to connect in Venice, of all places, and our potential future collaborations. Similar conversations took place at the Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa exhibit in the Applied Arts Pavilion. I had a great exchange with one of the curators, Ghanaian-born curator Nana Biamah-Ofosu, that serendipitously developed into a group conversation with London-based, Sierra Leone-born architect Joseph Conteh, and Nigerian architect Adeyemo Shokunbi who were also visiting the exhibit. We had extended conversations about Demas Nwoko (Golden Lion winner) and the long history of his contributions to African art and architecture. We discussed the effects of Tropical Modernist discourse within the context of its Modernist formation, and its impact on the African built environment, as well as our efforts to pedagogically inform the next generations of African and diasporic led contributions to architecture. These exchanges were incredibly edifying. And though there is an urgent need to significantly decentralize the locus of architectural expressivity from the legacies of the Venetian exhibitionary context, the opportunity to gather amongst peers and share our pedagogical ideas and experiences in moments of heightened visibility at the Biennale was significant. With that said, it is absolutely incumbent upon all of us to establish the conditions that will enable local technicities to emerge within the dignity of their social, aesthetic, cultural, and architectural contexts.

We, as architects, artists, academics, and practitioners of varying kinds are positioned to shape architectural discourse in a manner that meaningfully produces culturally responsive, climate-sensitive relations to the natural and built environment. Consequently, what African, Indigenous, and diasporic experiences teach us about spatial expressivity in this regard is that architecture is a site of field relations and enduring liaisons—ritualized territories and technicities suffused with culture, distributed throughout the world. In many respects, we are called to not only practically resolve but materialize the architectural poetics of cultural relation that inspired Martiniquais writer and philosopher Édouard Glissant in ways that both meaningfully reveal our vibrant, transatlantic multiplicities and strategically conceal or preserve aspects of culture that must necessarily exceed the Western, commodifying demand for cultural legibility and transparency at all costs. There must be a transgressive ethos to erode artificial borders that seek to undermine or regulate African, diasporic, and Indigenous expressivity in the rich domain of architectural relations. They must be read through and for local producers of culture in their own environmental contexts, necessarily rendering substantive cultural opacities.

What is a relation?

We are reminded, as Senghor implored, to put down the object, to…dance the other.

Alan Dunyo Avorgbedor is an Assistant Professor at McGill University’s Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture. His research explores the ways in which African Technicities, as a suite of culturally embodied dwelling practices, informs sensorial, hodological, and ultimately epistemological relationships within natural and built environments in sub-Saharan Africa and across the diaspora. Avorgbedor is currently authoring a monograph on African Technicities.

Avorgbedor is also multi-modal artist engaged in a practice that explores the poetics of audiovisual analog instrumentation, film photography, and modular synthesis. He performs interference signals, animating their figural and chromatic aberrations in correspondence with analog transport systems, to modulate the expressive character of the medium. Avorgbedor is currently working on a series of interference portraits of contemporary and historical African and diasporic figures oscillating at the margins of architectural and mobilities discourses.

Notes

- See Lesley Lokko’s May 18, 2023 statement concerning these events during the opening press conference. https://static.labiennale.org/files/architettura/Documenti/statement-lokko-18may23.pdf.

- Lokko, May 18, 2023 statement. Ibid.

- From all appearances, it was merely Neoplatonic at its weightiest.

- See Achille Mbembe’s On the Postcolony and Necropolitic (Oakland, CA: University of California Press; First Edition, 2001). Like Foucault, Mbembe is interested in social mechanisms of power that effectively control and produce a certain type of individual, or a certain kind of set of possibilities, or certain kind of subject formation. Mbembe theorizes postcolonial borders and territories through an expanded Foucauldian reading of Governmentality and Power that organizes the world into racialized zones of socioeconomic potential, participation, and life, and zones of relative death. He explores this through the violence, exploitation, and legacies of colonial power.

- Lesley Lokko, “Agents of Change,” in The Laboratory of the Future: Biennale Architettura 2023 (Venice: La Biennale di Venezia, 2023), 40.

- See Kenneth Burke, Language as Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature, and Method (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 1966).

- See Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993).

- See, for instance, David Aradeon, “Space and House Form: Teaching Cultural Significance to Nigerian Students,” Journal of Architectural Education 35: 1 (1981): 25–27. See also his curatorial work on the antecedents of Afro-Brazilian Spaces.

- Lokko, May 18, 2023 statement. Ibid.