Review By: Sina Brückner-Amin

January 17, 2025

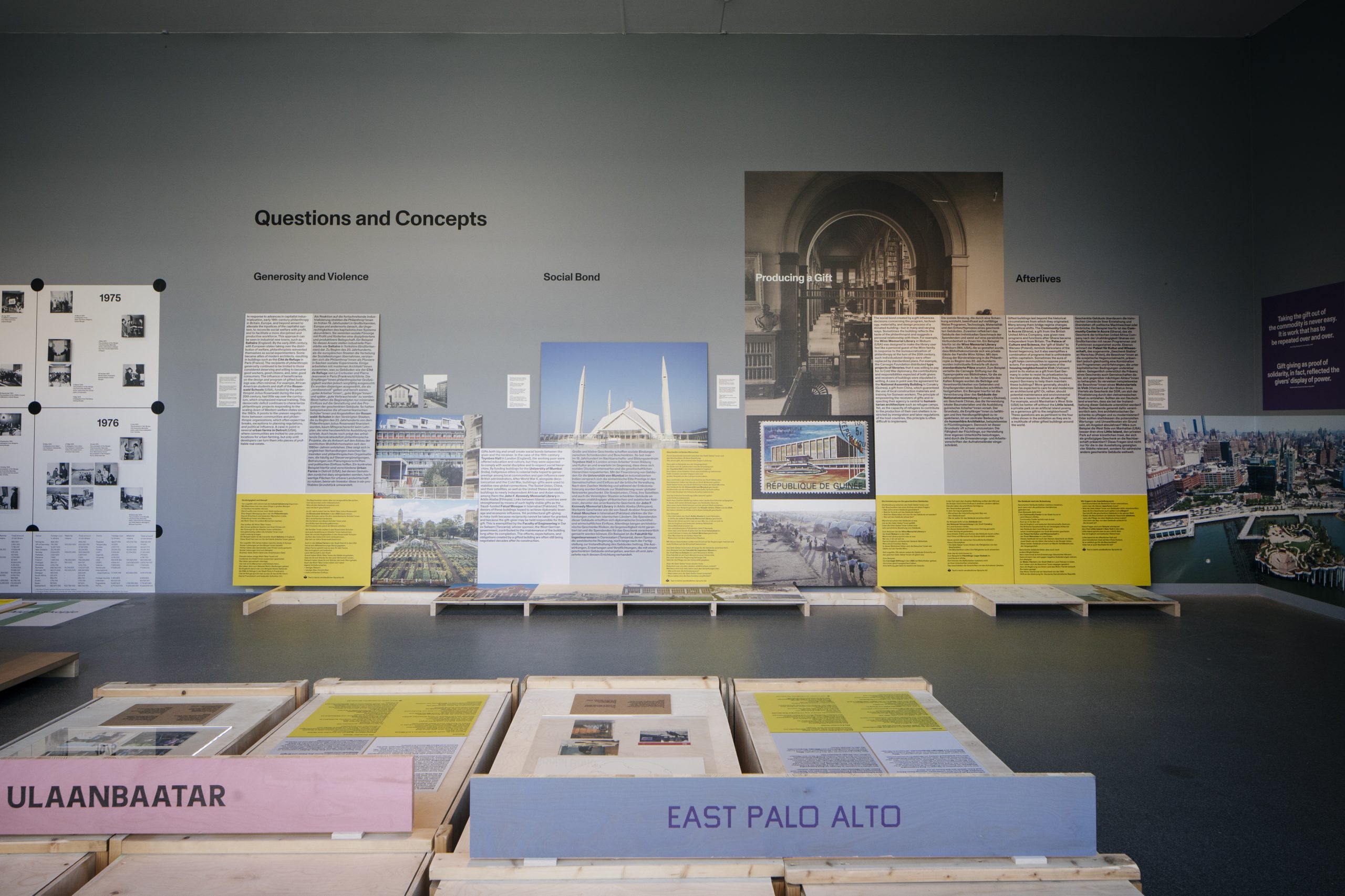

Gift-giving is an act of negotiation: between the giver and the recipient, expectations and performances of gratitude, acceptance and reciprocity. The exhibition “The Gift” at the Architecture Museum of the TUM sets out to investigate such cases of “generosity and violence” by siting them in architecture. Yet one should not be misled by the title’s enumerative character; from the outset “generosity” and “violence” are established as two poles between which all gifts inescapably hover. The title might as well have been “from generosity to violence,” as the drastic economic effects of these one-off gifts evolve over time. They leave deep ruptures in local ecologies and highlight that violence begins where gifters position themselves in the illusion of a permeable global reality. The notion of the gift examined is thus far from simple, and curators Damjan Kokalevski and Łukasz Stanek grapple with the underlying question of how to convey a set of relations through the medium of an exhibition, and which concrete examples can best illustrate them.

Figure 1: © Architekturmuseum der TUM, photo Ulrike Myrzik

The exhibition outlines three main concerns: the actual production of buildings (including actors and stakeholders, materials, and design), the question of reciprocity and possible counter-gifts, and the afterlives of gifted buildings in the sense of responsibilities and maintenance. These concerns are explored in four case studies, bookended by a theoretically-driven introduction and a multifaceted epilogue, which address the slippery nature of the overall concept of the gift. The reconstruction of Skopje following the 1963 earthquake is framed as a “Humanitarian Gift;” in Kumasi, a university’s ambivalent roles are discussed as the aftermath of a “Gift of Land;” a “Diplomatic Gift” in Ulaanbaatar is retold through a personal narrative; and East Palo Alto is framed as a site for grappling with the consequences of “Philanthropic Gift[s].” In these four cases, architectural gifts may be tangible—actual buildings, pieces of land—but their circumstances illustrate how the line between developmental aid, diplomacy, philanthropy, sponsorship, and investment is oftentimes difficult to draw.

Figure 2: © Architekturmuseum der TUM, photo Ulrike Myrzik

With their attention to economic concerns, the exhibition’s research materials tie into a growing body of scholarship interested in the dependencies between developmental aid and (post-)colonial interventions in the Global South. They draw from Łukasz Stanek’s earlier work, including the conference “The Gift of Architecture: Spaces of Global Socialism and their Afterlives” held at the University of Manchester in 2022 and his impressive book Architecture in Global Socialism: Eastern Europe, West Africa, and the Middle East in the Cold War (2020), which explores architectural mobilities between socialist and post-colonial states. In the latter case, built and infrastructural gifts feature prominently as acts of foreign policy. The Skopje case builds on Damjan Kokalevski’s PhD research and subsequent publication Skopje Walkie Talkie (with Susanne Hefti, 2019), which addresses how large-scale city redevelopment in the 2010s, fueled by right-wing populist politics, rewrote the legacy of 1960s-era humanitarian architectural interventions. These accounts can be situated in relation to architectural histories of humanitarianism such as Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi’s Architectures of Migration (2023), Ayala Levin’s account of colonial developments in Sub-Saharan Africa, Architecture and Development (2022), and explorations of the deferral of independence in the Global South, as in the V&A-produced exhibition Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa (curators Christopher Turner, Nana Biamah-Ofosu and Bushra Mohamed, 2023) at the Biennale di Venezia. While these works illuminate multifaceted politicized planning processes or aesthetic interpretations of “imported” architecture from Global North to South (or West to East), in “The Gift” these issues move to the background to highlight the longer-term societal and developmental impacts of philanthropically intended interventions.

Figure 3: © Architekturmuseum der TUM, photo Ulrike Myrzik

Inside the Architecture Museum, the exhibition design lends itself to the airy, long rooms and follows a linear narrative through designated case-study areas, defined by irregularly formed clusters of modular wooden frameworks. In the institution’s history, curators frequently opted for extensive subdivisions, which increased hanging space but also produced large amounts of waste after an exhibition was taken down. “The Gift” rethinks this practice by working with reused wooden panels provided by the Munich-based Treibgut, an initiative that collects and repurposes used materials from local cultural institutions. Accounting for roughly one third of “The Gift”’s structural materials, these become almost an exhibition in themselves, with their aesthetic of precarity standing in glaring contrast to the grandiosity of many of the case studies, which would have been amplified with a high-end exhibition production. Here, it is all structure, no cladding; everything is leaned on, laid down, or somewhat brutely nailed in. The resulting informal charm not only dethrones these large-scale projects; it also stages an approachable environment whose atmosphere is reminiscent of the disorder, abandonment, and appropriation that architectural gifts (oftentimes) provoke in their aftermath.

Figure 4: © Architekturmuseum der TUM, photo Ulrike Myrzik

Still, across all four “stories,” text is first and foremost the content of the exhibition. For the exhibition viewer, this gives the impression that other media–photographs, film footage, maps–must be explained to understand how they operate in relation to the overall concept. But these materials also tell their own stories. In some instances, the displayed things demand just as much attention as the numerous texts next to them. The history of Skopje becomes vivid through the archival finds presented: maps and pamphlets from the UN’s call for global aid after the earthquake, numerous photos of the actors and the construction projects. Ulaanbaatar’s housing blocks, known as “the blue gift of Brezhnev” due to their iconic coloring, are portrayed from the inside out through one family’s history in their gifted apartment, mimicking a glance into their private photo album. East Palo Alto and Kumasi’s cases, however, are depicted almost solely through videos and photographs taken by the exhibition’s associated researchers, making them exercises in another form of preservation–listening takes the place of reading.

Figure 5: © Architekturmuseum der TUM, photo Ulrike Myrzik

In these four cases, it is the economic and spatial minutiae that productively complicate the nature of architectural gifts: How do locals deal with the once British-funded college campus at Kumasi, today expanded into the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, which offers jobs and economic development, but is built on land that is actually just leased and could be used by local residents for other purposes? Where does structural inequality begin in East Palo Alto, in the growing number of schools and community buildings built by tech giants (“philantrocapitalists”) or in the state-built freeway decades earlier, which, like a gift to the white population, virtually cut off the marginalized districts? A kaleidoscope of questions unfolds, which one wishes could be explored as rigorously as they are posed–but the medium of the exhibition reaches some of its limits. While the evidence is rich and reacts against a longstanding tradition of architectural exhibitions which present decontextualized materials in auratic settings, the storytelling materials come across as somewhat dry. It should be acknowledged that spending over two hours in an exhibition to read through panels may not be an experience accessible and appropriate for a wider audience. Given that so much heavy lifting is done by text and interview work, it is not surprising that the materials will inform a forthcoming book by Stanek. In the larger picture of architectural research, it is also worth considering if an online map or a documentary film would have provided a suitable alternative medium for the curators’ intentions.

Figure 6: © Architekturmuseum der TUM, photo Ulrike Myrzik

Figure 7: © Architekturmuseum der TUM, photo Ulrike Myrzik

This is to say that “The Gift” tackles an incredibly complex topic by presenting tiny slices of a global reality: that of intertwined relations full of intricacies, intentions, dependencies, and delicately handled rhetorics, in which the ascriptions of “generosity” or “violence” fluctuate between actors and chronologies. The exhibition raises more questions than it can answer in this setting, yet these are its strongest contributions, pointing to gaps in practice and research, such as the long-term study of the multitudinal effects of built architecture. By prompting gift-giving as a relational condition and stressing the how instead of the what, the project ultimately encourages the investigation of other sites—mundane or grandiose—in architectural history to uncover important yet seemingly intangible political dimensions. It is the uniquely grounded perspectives, more than the attempt to unify singular episodes as part of a global historical phenomenon, which complicate the discipline’s commitment to decolonial practices by exposing the collateral effects of so-called generosity.

Sina Brückner-Amin is an architectural historian, media scholar, and curator. She is a postdoctoral researcher at KIT Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and the saai | Archive for Architecture and Civil Engineering. Her research focuses on institutions and bureaucracy, (non-)architectural media, and histories of planning. She completed her PhD at the LOEWE Cluster “Architectures of Order: Practices and Discourses between Design and Knowledge.” She previously worked in curatorial positions at the Architecture Museum of TUM and the Max-Planck-Institute for Empirical Aesthetics and curated a cabinet exhibition at the DAM Frankfurt.