Review By: Wanda Katja Liebermann

August 23, 2024

David Gissen’s slim but packed The Architecture of Disability: Buildings, Cities, and Landscapes beyond Access hits hard, suggesting “an entirely different relationship between the apparatus of architecture and architects in their engagement with disabled people” (139). Using original site interpretation and archival research, what he means by “different” is an epistemological transformation of foundational architectural concepts. Gissen adopts the lens of impairment and techniques of defamiliarization to upend durable architectural beliefs and position disability critique at the heart of contemporary architectural and urban debates. This is not new—the work of Elizabeth Guffey, Sun-Young Park, David Serlin, to name a few, offer penetrating takes on how disability theory can expose hidden cultural values and systems. However, unlike these scholars’ focus on designs for disability, Gissen’s reinterpretations of places for the general public suggest a more holistic rewriting of architectural history. Also, where most disability critiques of architecture emerge from other fields such as geography or disability studies, The Architecture of Disability offers the field’s first broad, serious engagement with disability. That this is JAE’s first review of a book on disability confirms architecture’s lag in treating impairment as fundamental to design discourse.

Both sweeping and pointillist, the book unfolds its arguments in six chapters: on monuments, nature, urbanization, form, interior environments, and tectonics. Gissen grounds his theoretical exploration by first dismantling access, which is architecture’s usual preoccupation with disability. While he lauds the efforts of disability activists to make spaces more usable by disabled people, he observes that this focus does not address the deep-seated ableist values embedded in architectural discourse and practice. Moreover, he argues, this mechanistic mindset reinforces normative beliefs about the body. His critique also contains a reproof of political liberalism that relegates disability to demanding more access from the margins. That is, asking for functional remedies only deals with the relatively discrete consequences of a core problem, instead of uprooting the values that produce inhospitable design.

The book develops two main themes. First is the recovery of disability in architectural history. Each chapter offers eye-opening examples, but “Impaired Monuments” and “Of a Weaker Nature” are the most captivating, perhaps because they deal with places that we think we know—Yosemite National Park, the Acropolis. To challenge inherently inaccessible and hostile framings of these places, Gissen shows how history has represented monumental spaces as empty of disabled people, or even human habitation. For example, remnants of a monumental stone ramp leading up to the Parthenon reveal disabled people’s existence in Athenian society. Similarly, in early photographs of Yosemite, Gissen draws our attention to Indigenous agricultural sites that predate its constructed image as a rugged Western sublime landscape. Refuting the image of these places as inherently inhospitable to all but the hardiest of constitutions changes our understanding of what kinds of bodies belong there.

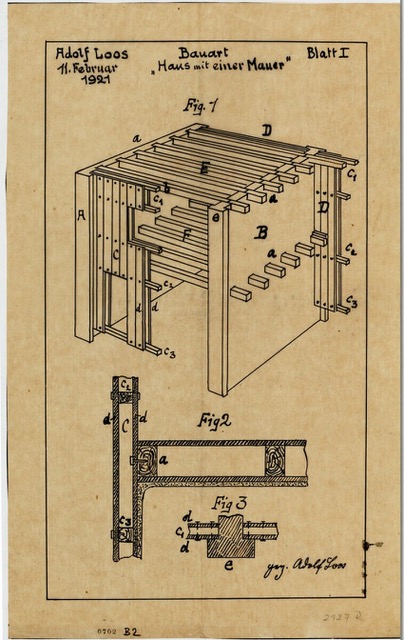

The second main argument reevaluates qualities associated with impairment. Disability activism recognizes the resourcefulness and resilience—“cripping”—that living in an impaired body in an ableist world demands. Gissen elevates scorned qualities attributed to disability like frailty, incapacitation, slowness, as important aspects of design. One of the most fascinating discussions focuses on informal housing built by disabled WWI veterans on Vienna’s outskirts. Both pragmatic and radical, these collectives developed ingenious ways for impaired individuals to construct their own homes through deliberate choices of materials, techniques, and dimensions. In Friedenstadt (Peace City), Heuberg, and Rosenhügel, builders’ self-reliance and independence from mass industry and the state enabled them to express anti-capitalist and anti-war beliefs. Gissen intimates that to root out ableism requires contesting capitalist ideology. Adolf Loos and Josef Frank, whom the city eventually charged with overseeing the settlements, studied and documented their innovations as the basis for further invention. These settlements can be understood as a model for self-build housing schemes such as the 1969 PREVI project in Peru and, more recently, Elemental in Chile, led by Alejandro Aravena.

Disability practices also offer novel ways to encounter and document historic and cultural artifacts and spaces. In “Impaired Monuments,” Gissen describes an audio recording of blind scholar Georgina Kleege’s “shorelining” of a Richard Serra steel sculpture with her cane. The tapping of stick on steel along the sinuous form provides a vivid example of the transformative potential of disability representation. This and other examples of imaginative practices reveal the banality of the usual forms of inclusion in art and architecture.

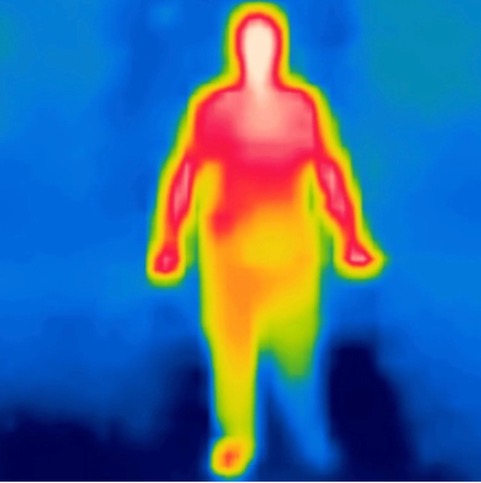

Less compelling chapters cover familiar territory about the scientific construction of the normative body. But they nevertheless contain important critiques of contemporary architectural research. In chapter 5 (“Disabling Environments”) Gissen draws on historical studies of interior environments such as Le Corbusier’s experiments with mechanically controlled spaces and thermoregulation to destabilize the concept of the “comfort zone”—the range of temperatures that the “normal” body finds comfortable. He notes instead that “health and comfort are processes achieved by people within a space, rather than parameters of the space itself” (112). The chapter includes a thermographic image of the author that reveals how his artificial limb defies the embodied norms of the high modernist “schematic subject”—personal, lived evidence for his argument (Figure 2). Showing that science-based research almost always reinforces a narrow concept of humanness is a needed retort to surprisingly tenacious architectural efforts to determine universal truths about bodies. Gissen’s observations implicate the body of scientific (or scientistic) architectural research, which, by drawing on the latest brain and computer science, appears as the future of architectural knowledge, while actually reiterating an outdated depoliticized Cartesian body.

Figure 2. Thermography of David Gissen by Philippe Rahm, 2019. Courtesy of David Gissen.

Chapter 4 (“A Form of Impairment”) presents the biggest challenge for practitioners and design educators. Identifying form as a “more intentional, philosophical system for dislocating the problems of aesthetic taste and apprehension from any social or political concept” (77), he denounces the mainstays of architecture disability discourse—form and function—as hollow targets. Gissen draws on nineteenth-century treatises by Heinrich Wöllflin and Gottfried Semper that correlate the proportions, symmetry, and resistance to gravity of buildings and bodies, ideas that still rouse aesthetic debate (see Christopher Hight, Antoine Picon). Form can’t escape this essential connection and, thus, “architectural form itself was defined in opposition to disability” (89). In other words, praising the beauty of accessible design reifies a shallow relationship between formalism and disability. Instead, Gissen borrows Tobin Sieber’s idea from Disability Aesthetics (2010) that creative experimentation can emerge from the evocation of disabled bodies. Gissen offers the example of West 8’s Madrid Río Park design incorporating bent-over pine trees conspicuously braced by red metal stanchions.

The book’s powerful thematic undertow is the importance of how we are oriented to architecture, to use Sara Ahmed’s term. While a focus on the personal (is political) is common in feminist, disability, and queer scholarship, it is still rare in architectural history. Gissen’s observation that “often scholars and designers center their prowess as a de facto quality of insightful architectural research and knowledge” (xvii) highlights this unmarked ableism. By contrast, he draws on his “comparative weaknesses and incapacities” as both method and theory for the book’s most trenchant interpretations. We are the beneficiaries of a historiographic and autobiographic convergence; the recent growing legitimacy of disability as a topic in architectural theory has allowed Gissen to transform a long suppressed yet essential part of himself into insight. This authorial reconciliation unsettles architectural doctrine.

Wanda Katja Liebermann is an architect and associate professor of architecture at the University of Oklahoma. Her research focuses on the relationship between theories and practices of architecture and urbanism and social justice movements. She examines the recursive dynamics between design practices, the built environment, and ideologies of identity, recognition, inclusion, and beyond. Her book Architecture’s Disability Problem (Routledge, 2024) critically analyzes the relationship between architecture and different conceptions of disability rights in the United States across pedagogy, policy, and practice. Its aim is to better understand the discipline’s narrow response to disability and explore creative alternatives.