April 2, 2016-September 12, 2016

Mudec

Today, digitally infused design methods have altered the way we think about details. Design schools and architectural firms commonly use BIM (building information modeling), engineering, and other 3-D modeling software programs equipped with readily available manufactured products, building components, and preconfigured assemblies that can be “dropped into a building” during the design process. These preconfigured elements promote certain industries over others, diminish the need for custom solutions, and create ease in copying details as “data” from one project to another. As a result, the design student or practicing architect doesn’t have to think through particular building connections as actual design problems. But our current design generation is also governed by a prolific “making culture,” where “file to product” craft practices are trying to reclaim the architect-designer as master builder. This shift seems to promise a renewed meshing of design and industry amidst transmuting fabrication technologies, yet it also makes us wonder, as Semper did, whether tectonics belonged more to the conceptual realm or the savvy maker?3 Is the priority of the design idea being compromised or dictated by technique, and can design details still be instrumental as an element that unifies the two?4

These concerns about “thinking through craft” in design appear to be fittingly investigated at Milan’s Twenty-First International Triennale, Twenty-First Century: Design after Design. Responding to the Triennale’s long-standing postwar mission, “to stimulate the relationship between industry, art and society at large,” the exhibition Sempering—Process and Pattern in Architecture and Design gathers artifacts from the last decade that point to a resurgence of craft-driven ideologies. Curated by Milan’s School of Design Dean, Luisa Collina, and local Italian architect Cino Zucchi, this exhibition looks at industry’s role in idea-forming relationships of form, matter, and production by uncovering copious fabrication approaches and systematically structuring them around eight modes of making: stacking, weaving, folding, connecting, molding, blowing, engraving, and tiling. Deciphering Semper’s numerous classifications, Collina and Zucchi conjured up this explicit set of “operations,” imagining how Semper might have looked at craft techniques in the twenty-first century. They asked: “Which classification would Gottfried Semper adopt to interpret the plethora of artifacts … [and] sort through the multitude of ways through which ‘form takes shape’ in contemporary design?”5 As a hypothesis, the curators seem to have staged their findings through two lenses: first, by looking for concepts conveyed through each “act of making” across design fields, regardless of scale, function, material, trade, tool, or end product, and second, by bringing into focus the relevance of Semper’s cross-examination of techniques through selected artifacts employing hybrid design processes.

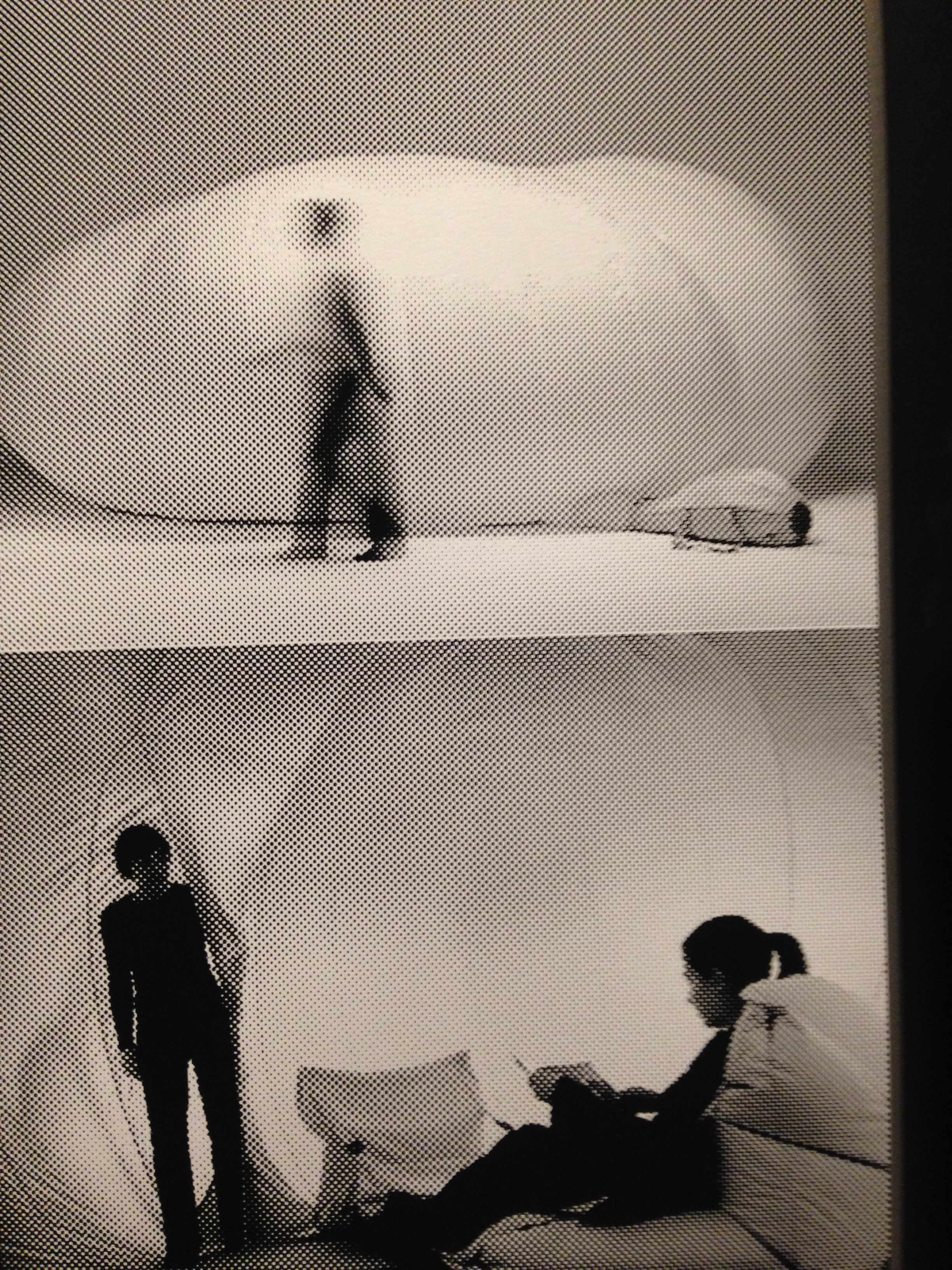

Interplay of hand and machine was also addressed. For instance, in Molding, Zaha Hadid’s fluted, folded plywood structure and patterned vase was achieved through manual and robotic production yet assembled and finished by hand. CODesignLab/Cascone’s ceramic columns were 3-D printed but playfully recall form and gesture from hand-braided fibers. Other works successfully “scaled-up” experiential qualities across design fields. For example, the buoyant essence in Margaux Keller’s hand-blown lamps was re-encountered in Monica Forster’s inflated Cloud Room Divider, and then again in Plastique Fantastique’s 60-foot-diameter bubble building, in the common ephemeral boundaries created by semitranslucent circular forms. While each form finds its outer limits by means of expansion, it is not made the same way. Thus, these form-making investigations suggest that the substance of an idea supersedes that of technique.10

Sempering is currently showing, until September 12, 2016, at the Museum of Culture (MUDEC) in Milan, Italy.

How to Cite this Article: Frangos, Naomi. “Sempering- To Craft a Detail, or Not?” review of Sempering – Process and Pattern in Architecture and Design, curated by Luisa Collina and Cino Zucchi. The Mudec, Milan, Italy, April 2 – September 12, 2016. JAE Online. August 22, 2016. https://jaeonline.org/issue-article/sempering/.