January 24, 2020-April 5, 2020

Nancy Johnston Records Gallery, Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, University of Oklahoma

Luca Guido (curator), Michael Hoffner (exhibition design)

Renegades: Bruce Goff and the American School of Architecture is the latest and largest issue of the American School Project. Led by University of Oklahoma faculty members Stephanie Pilat, Angela Person, and Luca Guido, the exhibition recounts the pedagogy, production, and influence of OU’s School of Architecture in the late 1940s-1950s, utilizing the archive they assembled of student work, departmental publications, and other ephemera.

Centering on Bruce Goff, who served as chair from 1946 to 1957, Renegades highlights the school’s curriculum and student work to demonstrate OU’s radical departure from the dominant Beaux-Arts and Bauhaus educational models of the period. This institutional ecosystem, dubbed the “American School,” drew upon the “organic” modernism of Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Sullivan, promoting an approach to design that was formally experimental, individual and idiosyncratic, and materially contextual.

While the physical exhibition was taken down early due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it lives on virtually through a meticulously constructed walk-through created with Matterport three-dimensional photography. Moreover, the curators have embedded the ability to zoom in on every item and its description, and to clearly read all of the wall text, allowing for an immersive experience.

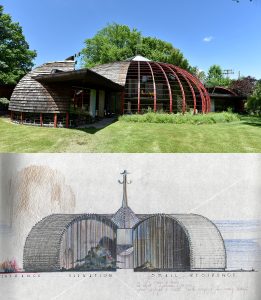

Renegades is divided into three main sections detailing the prehistory, activities, and aftermath of the American School. The largest section explores the curriculum, personalities, atmosphere, and design work of the architecture program at OU. The driving personality was undoubtedly Goff, whose “organic” approach to design expanded on the precision and abstraction of Wright and Sullivan blended with the material diversity and formal plasticity of Antonio Gaudi and German Expressionist architecture. Masterworks of the American School exemplify his approach. In Goff’s Bavinger House (1955), rough-blasted local sandstone walls studded with blue-green slag glass were arranged along a nautilus spiral, creating a cavernous space in which living and sleeping pods were hung alongside precariously airborne stairs. Herb Greene’s Prairie House (1961) playfully referred to the native prairie chicken and was covered inside and out with cedar shingles dynamically arranged to emphasize its awkward geometries. The projects’ drawings take center stage, revealing how the architects imagined and visualized such otherworldly forms and interiors.

The second section focuses on the nucleus of the American School Archive—namely, student work that the American School Project has collected from alumni. One set of drawings shows how students responded to weekly prompts to explore abstractions such as rhythm, translucency, and incident. It is striking just how impotent those terms are to describe, much less explain, the students’ responses: drawings of futuristic undersea settlements; geologic landscapes in which the architecture, flora, and terrain are indistinguishable; structures that are simultaneously organic and industrial; and alien megastructures set into the American wilderness.

The third section illustrates the legacy of the American School, highlighting the students’ and faculty members’ later built work. A large-format photograph of Chayo Frank’s AmerTec Building (1967), appearing as the exoskeleton of a Cyclopean sea slug, leads visitors around the corner to view a collection of surprising diversity. The amorphous shapes and dynamically placed cedar shingles found in Greene’s work continue to appear, as in Mickey Muennig’s Foulke Residence (1963). But the American School aesthetic expanded to include the rectilinear forms of Robert Overstreet, the more precise, symmetrical geometries of Frank Wallace’s designs for Oral Roberts University, and even the infrastructural scale of Donald MacDonald’s San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. The curators affirm the heritage value of the American School in a section on buildings that have been demolished, eliciting no small feeling of horror by pairing the original buildings with photographs of the banal, developer-designed boxes—or empty fields—that replaced them.

Goff’s assertion that the American School promoted unrestrained individual creativity inflected through client needs and local context, repeated uncritically throughout the exhibition, does little to explain its aesthetic cohesiveness: its formal exuberance within a fairly circumscribed family of forms, the graphical consistency of its science-fiction-inspired, surreal drawings, or its programmatic fixation with the single family house. Moments of clear influence between teacher and student are peppered throughout the exhibition, such as the relationship between Greene’s Prairie House (1961), based on an earlier drawing by classmate John Hurtig (1956-57), or Goff’s Ford House (1947), built on a structure of Quonset hut ribs, which clearly influenced a later house design by Hurtig (1957). If each student was encouraged to develop a unique and personal architectural language, and to reject all outside influences—even that of their teachers—how is it that the American School’s formal and graphic sensibilities remain so consistent?

This question, like many others that arise from an exhibition designed for a general rather than specialist audience, is addressed in the exhibition’s scholarly catalog where we learn more about the intellectual milieu of Norman, OK, and the community of artists who both served as a pool of enlightened clients for American School architects and supplied aesthetic models of engaging the local context.1 We also learn more about Goff’s desire to create an “indigenous” school of architecture at OU—a descriptor one might find objectionable given Oklahoma’s role in the Indian Removal Act of 1830 as the endpoint of the Trail of Tears and the forced relocation of 100,000 indigenous people from the American Southeast. In her essay “People, place, time, materials, and spirit,” historian and director of the Division of Architecture at OU Stephanie Pilat reveals the political undertones of the school’s claim to “indigeneity.” Goff positioned the “Americanness” of the school in contradistinction to European Modernism and its association (however simplified and misunderstood) with fascist, authoritarian governments. Following Wright and Elizabeth Gordon, editor of House Beautiful, Goff viewed the Modernist aesthetic of austerity and relative indifference to place as a “plot” encouraging inhabitants to “forgo their own taste, reject material prosperity, and accept less as more,” thus making them more pliant and open to “accept dictators in other departments of life.”2 In contrast to European educational models, the American School sought to provide an alternative “architecture of democracy” by which the values of individualism and self-sufficiency were reflected in architectural exuberance and idiosyncrasy.

Under Goff’s direction, the American School explicitly engaged in self-mythologization. This myth, tied up in notions of indigeneity and individuality, promoted architectural practice as a form of artistic practice in which the architect’s development and design products are unique and driven by personal interests, rather than by professional norms, collaborations with clients or builders, or disciplinary discursive engagement. Rejecting the contemporary use of historical precedent, Goff exhorted students to “learn what we can from [history], but forget it all when we need to create an architecture of our own. Do not try to remember.”3 This approach was central to the creation of a school of architects who were “not followers of a shared style,” but were “bonded together by their rejection of institutional norms and expectations.”4 The exhibition’s positioning of the American School as “renegade” perpetuates the School’s claims unchallenged, highlighting its defiance and independence, but leaving unexplored its aesthetic influences and intellectual commitments.

Endnotes:

Elizabeth Keslacy is assistant professor of architecture at Miami University of Ohio. She is an architecture historian whose work centers on the museology of architecture and design, the intellectual history of architectural concepts, and the reception of postmodern architecture. She is currently at work on a monograph tracing the history of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Her work has been published in the Journal of Architectural Education, Footprint, Thresholds, OASE, and Lotus International. Keslacy earned a MArch from the Southern California Institute of Architecture and a PhD in architectural history and theory from the University of Michigan.

How to Cite This: Keslacy, Elizabeth. Review of Renegades: Bruce Goff and the American School of Architecture, curated by Luca Guido, exhibition design by Michael Hoffner, Nancy Johnston Records Gallery, Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, University of Oklahoma, January 24, 2020 – April 5, 2020, JAE Online, November 20, 2020.