Review By: Janno Martens

September 20, 2024

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the war extended far beyond the frontline all the way into Western European homes. Soaring energy bills highlighted the powerful international channels through which energy and politics flow. Much like the systems that distribute them, the dynamics of energy connect the local to the global and pervade the histories that anticipate our twenty-first century crises. The theme raises questions about the role architects and urbanists play in today’s shifting energy and political landscapes.

This inextricable link between political and electric power, and the (infra)structures that sustain them, is the topic of the exhibition POWER, hosted at CIVA in Brussels. It is reflected in the show’s ample historical material, but also embodied in its venue: a decommissioned nineteenth-century power plant which has housed CIVA since 2000. POWER shows archival drawings and documents alongside contemporary photography and video work, (animated) maps, scale models, and sculptural installations courtesy of some fifty contributors. It refrains from aestheticizing energy or providing the obligatory Instagrammable photo-op: aside from the presence of a decommissioned “low voltage feeder,” which adds some grit to the space’s white walls and carpeted floors, the material is presented in a traditional (and somewhat cramped) museal setting.

Feel the Heat (2023), a site-specific installation consisting of infrared ceiling-mounted heating modules that run only when motion is detected, provides a gloomy introduction to the otherwise brightly lit exhibition. Developed by TU Delft’s Design, Data and Society Group & The New Open project in collaboration with Meta Office, it was intended to heat the exhibition space in a more efficient way. However, conservation and insurance standards restricted its adoption to the entryway alone–a reminder that barriers to energy efficiency are as much legislative as they are technical, especially within heritage contexts. Architect Philippe Rahm’s Red Carpet (2023) confronts this issue with more traditional means: leveraging the thermal properties of fabrics, Rahm improved the space’s energy efficiency by carpeting its floor with a specially developed red wool.

Figure 1: POWER, exhibition view, photo by Filip Dujardin

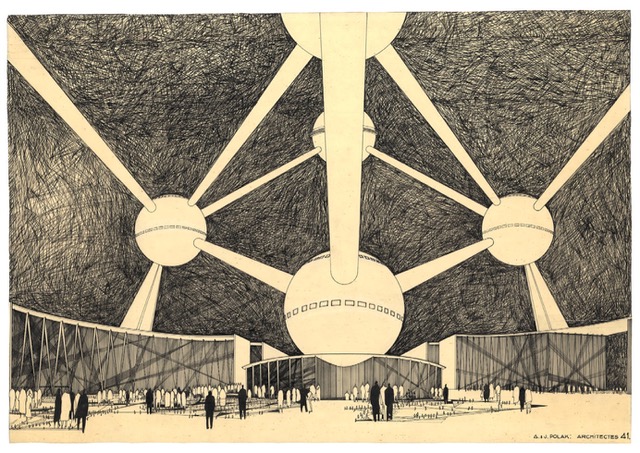

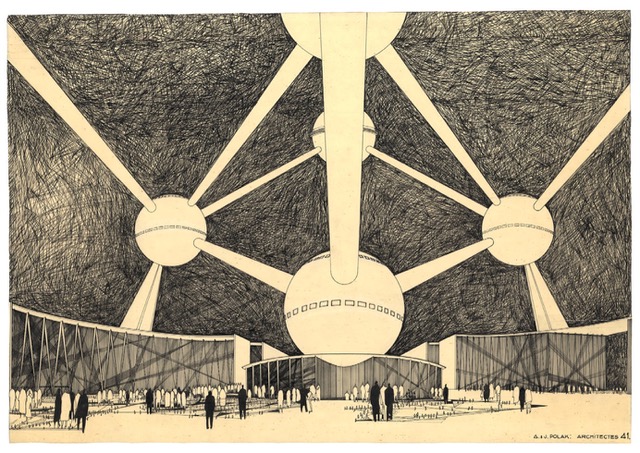

After these contemporary interventions, the exhibition takes a historical turn. A section devoted to the 1958 World’s Fair illustrates how Brussels not only became the EU’s legislative center and metonym, but also served as a nexus of the union’s political economy of nuclear resources. POWER presents the fair’s iconic 102-meter-tall Atomium as the physical manifestation of an atomic pax americana: by providing the United States with uranium from its Congolese colony, Belgium could construct Europe’s first commercial nuclear reactor. Unrealized plans for its erection on the exhibition grounds prove just how far local and national governments were prepared to go to render this program visible and accessible, while the presence of pavilions for the UN, Euratom, and the European Coal and Steel Community reveal the extent to which international politics, colonial resources, and energy technologies were intertwined at Expo 58. Design drawings for these projects show how architects physically shaped these matrices of politics and energy. Yet they seem to have had limited agency, let alone critical engagement, within this narrative; when faced with the intersections of the political power of national governments and the energetic power of the atom, the force of architecture and design pales in significance.

Figure 2: Andé & Jean Polak Expo 58, Atomium, bottom view from the Esplanade. CIVA collections, Brussels

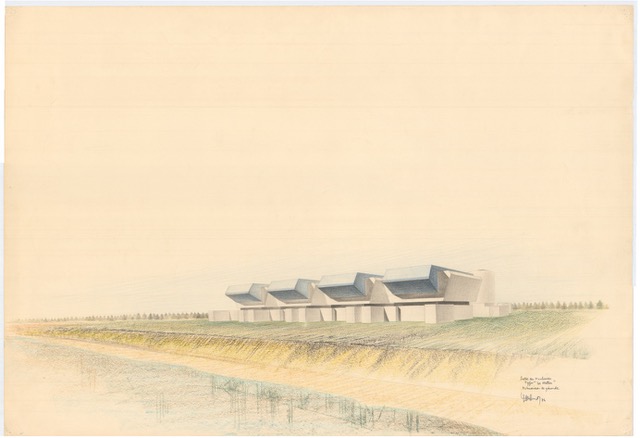

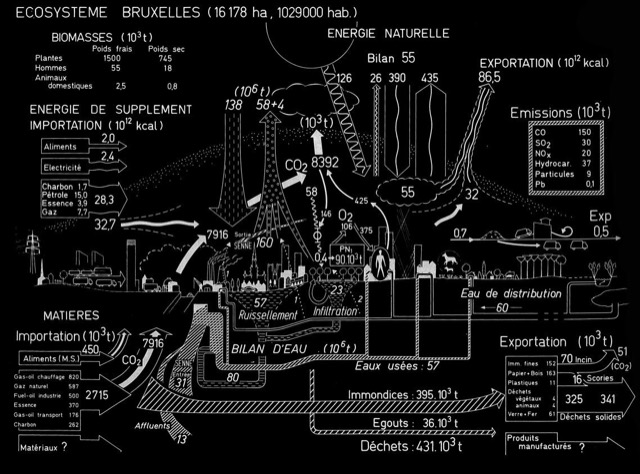

In material from the 1970s and 80s, architects and urbanists assume less modest roles–either by realizing nuclear ambitions or providing alternatives to them. The crayon-colored drawings by architect Claude Parent are an example of the former. His designs for nuclear power plants mediate the technological with the bucolic: Parent envisioned the tectonic drama of draft cooling towers and brutalist reactor shells not just as “temples” for the atom, but also as monumental anchors that would supply their rural environs with places for leisure. The analytical work of Paul Duvigneaud, a Belgian biologist, falls squarely in the other category. Combining bird’s-eye views of energy landscapes with diagrams of ecological systems, Duvigneaud’s drawings advocated for the integration of circular agriculture with decentralized and sustainable energy sources. Although he pursued his “socio-ecological utopia” primarily through scientific and political channels (e.g. by writing the environmental program of a political party), Duvigneaud also made significant contributions to the design disciplines through his pioneering work in urban ecology. Parent and Duvigneaud both leveraged scientific discourses to rethink the relation between built and natural environment, but their respective visual regimes reveal fundamental differences: pastoral versus urban, complicit versus critical. Parent’s work represents a traditional and arguably dated belief in the autonomy of architecture and the expressive power of built forms, whereas Duvigneaud aligns more closely with contemporary discourses that emphasize system-based and ecological approaches to the built environment.

Figure 3: Claude Parent, Exploratory Studies for Nuclear Power Plants, 1970 – 1980, © Claude Parent Archives & SIAF / Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine / Archives d’architecture contemporaine — Fonds Parent, Claude (1923 – 2016)

Figure 4: Paul Duvigneaud, The Brussels ecosystem, 1974 © CIVA Collections, Brussels

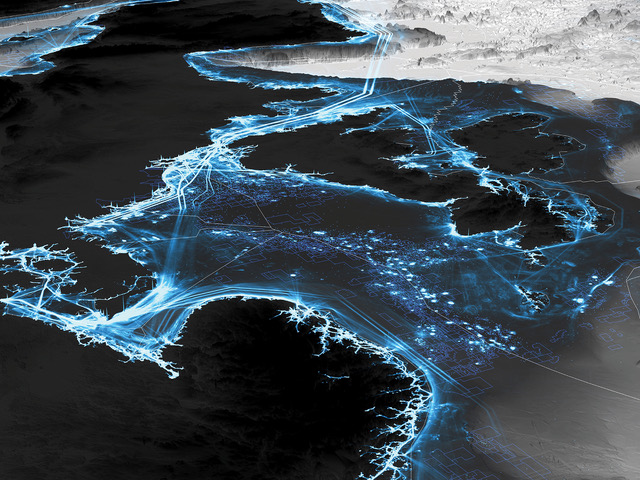

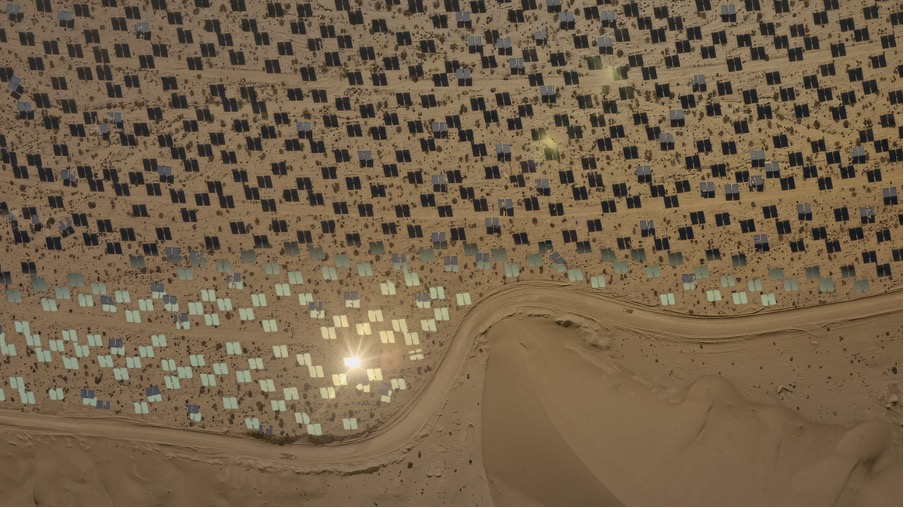

Duvigneaud’s efforts to analyze and “re-present” the environment through diagrams and cartography also tie POWER’s historical material to contemporary projects. While better known visualizations such as Buckminster Fuller’s World Energy and Energy Slave maps (1940) and OMA’s Eneropa Map (2010) speak to the relationship between borders and energy resources, arguably the most powerful—and thorough—mapping exercise on display is The North Sea Room—The architecture of the continental shelf (2023) by Territorial Agency. Their animated maps and graphs reveal how the submarine territories of the North Sea continental shelfs are shaped by fisheries, oil prospecting and drilling, telecommunication cables, and maritime transport routes. In contrast to this presentation of the enigmatic “North Sea technosphere,” a video work by Liam Young and a sculptural installation by Rachel Armstrong, Rolf Hughes, and Anna Vershinina push visualization into a speculative realm. But the “radical optimism” of Young’s The Great Endeavor (2023), which looks at the technological sublime of large-scale carbon capture efforts, fails to address the political dimensions that pervade the rest of the exhibition. The bizarre apparatus that is Armstrong, Hughes, and Vershinina’s Xenomorphic Energy: Necromantic Orchid (XENO) (2023) stages a flower-like sculpture filled with fluids that supposedly draw energy from silts and mosquitoes as a critique of the commodification of electric energy. Straying from the exhibition’s common thread, XENO reclaims vitalist connotations of energy by thematizing altogether different politics—the politics of bodies, metabolisms, and social-cultural ecologies.

Figure 5: Territorial Agency—Museum of Oil: The North Sea Room, The Architecture of the Continental Shelf © Territorial Agency

Figure 6: Rachel Armstrong, Rolf Hughes, Anna Verschinina, Xenomorphic Energy: Necromantic Orchid (XENO), 2023, photo by Filip Dujardin

Given the exhibition’s title, we are perhaps better served by complicating the notion of power rather than energy. Power, as Michel Foucault famously pointed out, “is not an institution, and not a structure; neither is it a certain strength we are endowed with; it is the name that one attributes to a complex strategical situation in a particular society.” (The History of Sexuality: An Introduction, Volume I, 1978, 93). POWER certainly offers insight into the manifold “complex strategical situations” anchoring the exhibited projects. But the particularities of the societies in which they emerged, so clearly elaborated for the Belgian context in the case of Expo 58, could have been expanded to other aspects of the show. The political party for which Duvigneaud was active, for example, was founded to defend the interests of the francophone community in Brussels, which raises questions about the relation between the politics of identity and the politics of ecology. And the Democratic Republic of Congo is arguably more significant for energy politics today than it was in the 1950s due to its abundant deposits of lithium, a crucial element for manufacturing batteries. Although indirectly addressed in Sammy Baloji, Jean Ktambayi Mukendi, and Daddy Tshikaya’s sculpture Tesla Crash, A Speculation (2019), a more in-depth consideration of the postcolonial aspects of contemporary resource extraction and distribution could have offered a valuable counterpoint to the political agnosticism of projects such as the Eneropa Map or The Great Endeavor.

Figure 7: Liam Young, The Great Endeavor, Humanity’s Largest Construction Project, 2023

Doing full justice to the complexities of “strategical situations” and societal vicissitudes is difficult enough in book-length studies, let alone exhibition texts. Yet in Armin Linke’s photographs of control centers, board rooms, uranium mines, and concrete canyons of hydroelectric dams, displayed in the center of the exhibition, the intricate flows of power become not only visible, but almost tangible. While the narratives of the exhibition allow us to think about energetic dynamics, Linke’s photos make us feel them. The awe that they inspire also foregrounds a disquieting conclusion implicit in the rest of the show: although architects, designers and engineers are empowered to participate in large-scale energetic transformations, the awesome flows of politics and energy may also leave them powerless.

Figure 8: POWER, exhibition view, courtesy of Armin Linke, photo by Filip Dujardin

Janno Martens studied philosophy and architectural history at the University of Amsterdam. Interested in the intellectual history of postwar architecture, he researches the influence of notions of space and environment on architectural thought and practice. Janno is currently a PhD candidate at KU Leuven with a grant from the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO), where he is investigating how technological and psychological notions of environment shaped American architecture and urbanism between 1964 and 1984. Before that, he worked with Erik Rietveld (University of Amsterdam / RAAAF) on the relation between architecture and ecological psychology and served as coordinator of the Jaap Bakema Study Centre in Rotterdam.

https://doi.org/10.35483/JAEOR.9.20.2024