Beatriz Preciado

MIT Press

One of the first things you may notice when reading Beatriz Preciado’s Pornotopia: An Essay on Playboy’s Architecture and Biopolitics (Cambridge, The MIT Press, 2014)—a fascinating text that unravels the effects of the Playboy empire across architecture, urban territory, media, gender, and sexuality—is the (relative) lack of historical photographs and images. Instead, the book’s first chapters (and cover) are illustrated by line drawings of referenced images, by Barcelona-based artist Antonio Gagliano. The drawings are, at first, confusing when juxtaposed with the text, which describes in detail the impact of Playboy’s increasingly saturated and “realistic” images: from the first vivid centerfolds of Playboy magazine (“Prior to Playboy, few men had ever seen a color photograph of a nude woman,”)1 to the lush illustrations of speculative modern architectural design in the adjacent pages.

It is not until the book’s short but significant postscript that we learn the reason for the omission of traditional visual archival material: Playboy Enterprise’s current Media Department objected to the content of a previous essay by Preciado on the grounds of the use of the word “pornography,” restricting access (and license) to the archive’s contents unless “pornography” was replaced with “art” (p. 226). Luckily for readers, this restriction did not deter Preciado from his research on Playboy.2 Instead, it reinforced the need for the investigation. “The archive is not a container of traces of the past but a performative machine for constructing the future,” Preciado writes. “There is no archive without violence. … This questioning of the archive aims to act as an epistemic act of disobedience” (p. 227). Reading Pornotopia as a scholarly act of disobedience gives extra resonance to the compelling text. Through the book’s in-depth documentation of how we—“necrophiliacs”3 all—live in the carcass of Hugh Hefner’s pornotopia whether we like it or not, Preciado offers an opportunity for critical reflection on Playboy’s legacy.

In one example, Preciado introduces us to a “centerfold” more successful than the naked women who were typically captured in the double-wide foldout pages: the architectural rendering of the unbuilt Playboy Townhouse (1962), designed by architect R. Donald Jaye.5 Preciado shows how the Townhouse was rhetorically defined in opposition to the suburban single-family house: it boasted glass instead of shutters, electronically controlled shades instead of floral curtains, responsive chaise lounges instead of plush sofas. In both the speculative Townhouse and other paper architectures, like the Playboy Penthouse (published in 1956), Preciado documents Playboy’s creation of an architectural fantasy: an urban, “boys only” structure armed for the repeated though temporary affairs with women, equipped with such paradoxical devices such as a “Kitchenless Kitchen” (of course, sans housewife). Even furniture aided the inhabitant in his seduction tactics, such as a cabinet with a hidden bar—so that the playboy would not have to leave the room to fix a drink, returning to find his date with “her mind changed, purse in hand, and the young lady ready to go home, dammit.”6 A machine for living in, par excellence.

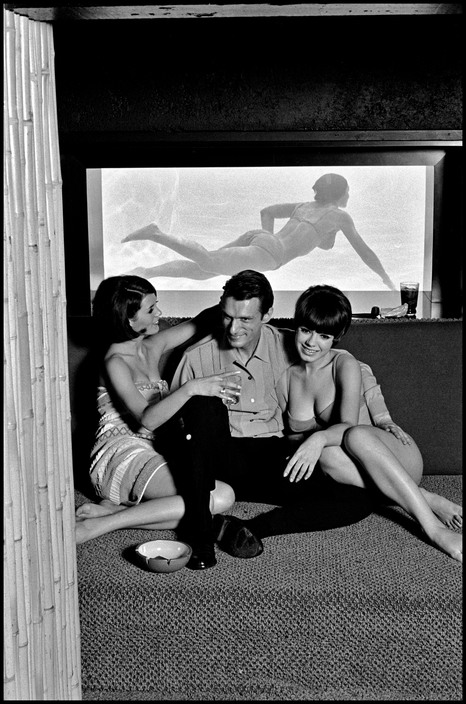

Preciado’s investigation of the “playboy” emerges from a legacy of writing on domesticity and gender, such as Beatriz Colomina’s Domesticity at War, which documented the role of modern design on the World War II “home front.”7 Pornotopia continues this conversation by exploring a newly masculine architectural interior in the postwar period, emerging potentially in response to concurrent waves of feminism that expanded the domain of women outside of the home. The playboy is framed as an “indoors man”—an urbanite who appreciates women, design, and silk robes—in comparison to the “outdoors man”—an avid, sportswear-donning, monogamous suburban husband, to whom Playboy magazine’s competitors such as Field & Stream appealed. Looking beyond this ideological relationship between the “indoors” and the new masculine identity, Preciado situates the concept of the interior in a larger conversation on emergent technology in the period. He looks, for example, at the Playboy Mansion in Chicago, an HQ for Hefner as well as a public club. Preciado contrasts the traditional stone exterior of the building with the heterotopic interior: a “sexual utopia” that was “extended and supplemented by electronic surveillance and communication systems,” such as a subterranean tiki pool flanked on all sides by recording devices. Pornotopia documents what Preciado calls a “spectacle of interiority” in which domestic space was no longer private, but rather a place of work and immaterial labor, in which a network of recording devices and media screens replaced Modernism’s symbolic transparent façade.

Against the backdrop of today’s social media landscape, which often seems dominated by click-bait-ish reports of the same (dismal) statistics on women in architecture, it’s possible to forget that Preciado’s text continues in a longer tradition of nuanced texts on architecture, sexuality, and gender, including edited collections such as Joel Sanders’s Stud: Architectures of Masculinity (Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), Francesca Hughes’s The Architect: Reconstructing Her Practice (MIT Press, 1998), or Beatriz Colomina’s Sexuality and Space (Princeton Architectural Press, 1996). Still, some historiographies argue that the extents of texts on architecture and sexuality remain sadly limited.8 In either case, Preciado, who cites his frameworks as coming from queer, transgender, disability, and porn studies (p. 10)—rather than architectural history—is a necessary voice. Preciado deploys diverse ways of understanding historical material to theorize about its effect on lived experience. Both nuanced and specific in its research and arguments, Pornotopia’s main revelation—that Playboy deployed an architectural, pharmacopornographic regime in the construction of the modern male—after reading the book seems like a foregone conclusion: something we already knew but somehow forgot. In short, Preciado’s book reminds us of two deceptively simple ideas: first, that gender is constructed both like and by architecture and second, that a nuanced history of the way we think about gender, sexuality, and space has never been more necessary.

Against the backdrop of today’s social media landscape, which often seems dominated by click-bait-ish reports of the same (dismal) statistics on women in architecture, it’s possible to forget that Preciado’s text continues in a longer tradition of nuanced texts on architecture, sexuality, and gender, including edited collections such as Joel Sanders’s Stud: Architectures of Masculinity (Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), Francesca Hughes’s The Architect: Reconstructing Her Practice (MIT Press, 1998), or Beatriz Colomina’s Sexuality and Space (Princeton Architectural Press, 1996). Still, some historiographies argue that the extents of texts on architecture and sexuality remain sadly limited.8 In either case, Preciado, who cites his frameworks as coming from queer, transgender, disability, and porn studies (p. 10)—rather than architectural history—is a necessary voice. Preciado deploys diverse ways of understanding historical material to theorize about its effect on lived experience. Both nuanced and specific in its research and arguments, Pornotopia’s main revelation—that Playboy deployed an architectural, pharmacopornographic regime in the construction of the modern male—after reading the book seems like a foregone conclusion: something we already knew but somehow forgot. In short, Preciado’s book reminds us of two deceptively simple ideas: first, that gender is constructed both like and by architecture and second, that a nuanced history of the way we think about gender, sexuality, and space has never been more necessary.- See p. 26. Preciado quotes Gay Talese, as quoted in Playboy: 50s under the Covers (New York, N.Y.: Bondi, 2007).

- Preciado, self-described in the book’s introduction as “a transgender and queer activist,” published Pornotopia under the name Beatriz. In January 2015, in Libération, the French newspaper, Preciado announced that “Beatriz is Paul.” While the 2014 English edition of Pornotopia’s book’s dust jacket uses the pronoun “s/he,” I am using “him” and “his” per the Libération text. This is all in light of the book itself, which documents the complex construction and performance of gender across history, in both architecture and language.

- “The bad news is that Playboy’s pornotopia is dying. The good news is that we are all necrophiliacs” (p. 215).

- “It is possible to see Hugh Hefner as a pop architect and the Playboy empire as an architectural multimedia production company, a paradigmatic example of the transformation of architecture through media in the twentieth century” (p. 18).

- “The 1959 issue of Playboy containing the report on the Chaskin House sold more than a million copies, overtaking Esquire for the first time. … Hefner began developing a plan to build a house in Chicago modeled on the Chaskin House. … Although the house was never built, in May 1962 Playboy achieved another hit when it published the unbuilt designs in one of the most famous articles of the period” (p. 101).

- Playboy, September 1956, as quoted by Preciado (p. 88).

- Beatriz Colomina, Domesticity at War (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2007). Preciado is generous throughout the book in his references to Colomina’s work on similar topics, including Sexuality and Space (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996). A version of some of Pornotopia’s content also appeared in his essay in Colomina’s edited collection Cold War Hothouses (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2004) and was developed through coursework at Princeton School of Architecture. Preciado’s research on Hefner and the rotating bed has also since been revisited in recent scholarship on related topics, including Colomina’s “The Office in the Boudoir,” in OfficeUS Agenda (Zurich: Lars Müller, 2014). A current exhibition curated by Beatriz Colomina and Pep Aviles at the Elmhurst Art Museum in Illinois, titled “Playboy Architecture, 1953–1979” (open through August 28), continues to explore Playboy’s architectural legacy.

- Samuel Ray Jacobson, “Notes on Sexuality and Space” (thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2013).

How to Cite this Article: Lui, Ann. Review of Pornotopia: An Essay on Playboy’s Architecture and Biopolitics, by Beatriz Preciado. JAE Online. September 7, 2016. https://jaeonline.org/issue-article/pornotopia/.