REVIEW

OCTOBER 8, 2023–JANUARY 14, 2024

FRAMER FRAMED, AMSTERDAM

SAMIA HENNI AND MEGAN HOETGER (IF I CAN’T DANCE I WON’T BE PART OF YOUR REVOLUTION), CURATORS

SAMIA HENNI, MEGAN HOETGER, FRAMER FRAMED TEAM, EXHIBITION DESIGN

July 05, 2024

Between 1960 and 1966—during and after Algeria’s struggle for independence—France secretly conducted nuclear experiments in the Algerian Sahara that severely contaminated the landscape. Soon after, radioactive particles were measured as far as southern Spain, Nigeria, and Sudan. But the radioactive fallout affected the Algerian and French site workers and the nomadic and seminomadic tribes residing in the area the most.

Performing Colonial Toxicity, a captivating exhibition with a confusing title, created by architectural historian Samia Henni and curated by Megan Hoetger, exposes the devastating effects of this still largely unknown episode of France’s colonial occupation of Algeria. The installation, staged in the bright, industrial space of a former nineteenth-century factory building in Amsterdam, is part of a larger project that also comprises an experimental publication, Colonial Toxicity: Rehearsing French Radioactive Architecture and Landscape in the Sahara (2024), and an online repository of testimonies of victims of France’s nuclear program in Algeria, The Testimony Translation Project. Together they make a powerful appeal for the declassification of the official documentation of France’s nuclear experiments (still marked as top military secret), the cleaning up of nuclear debris spread across the desert, and the compensation of victims.

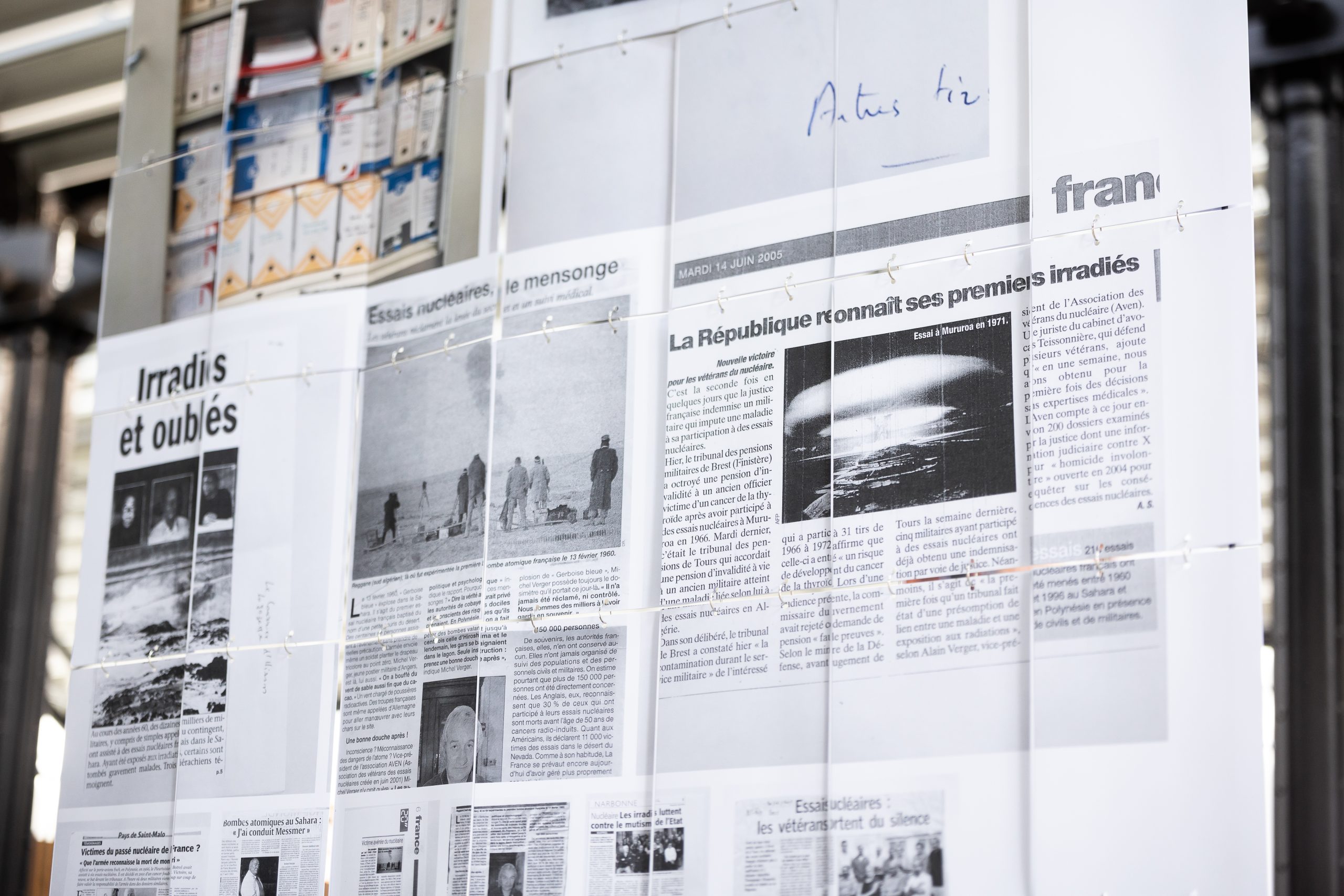

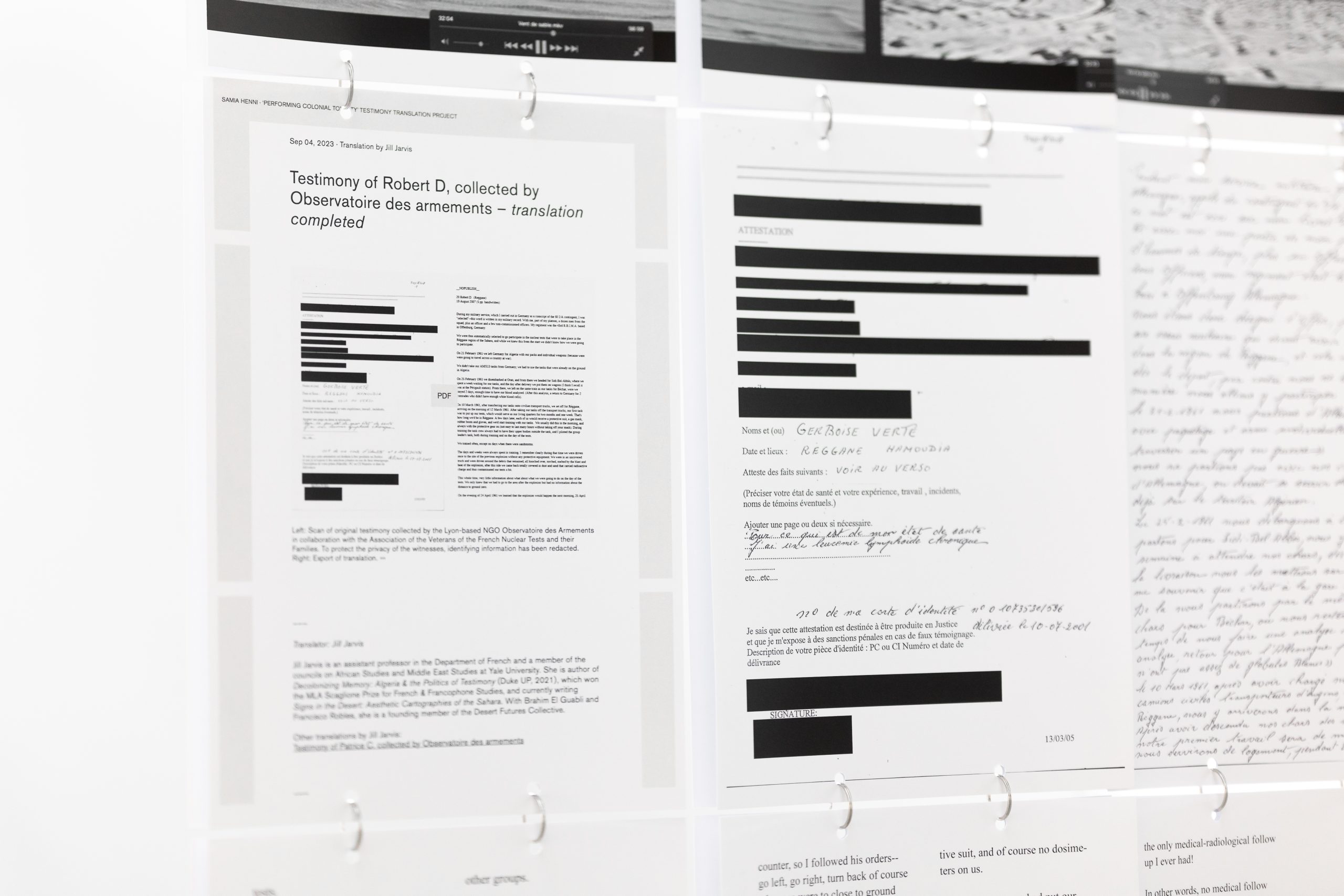

With architecture’s increasing focus on spaces of colonial violence, exploitation, and extraction, the desert has recently been the subject of several publications, including two themed issues of The Funambulist (2022)—which included an essay by Henni—and the Journal of Architectural Education (2023). This fascinating growing body of scholarship addresses issues such as the construction of American oil towns in the Saudi Arabian desert and Nubian resettlement villages in Egypt. But while most of this research still relies on official, often colonial, archives, Performing Colonial Toxicity takes a different approach. With the French archives still largely closed, Henni has created an alternative counterarchive for the exhibition. This includes transcripts of accounts by eyewitnesses and former employees, several translated from Tamasheq, the language spoken by some of the region’s tribes. Leaked documents, Google Earth images of the bomb sites, satellite imagery, newspaper articles, and stills from documentaries also feature.

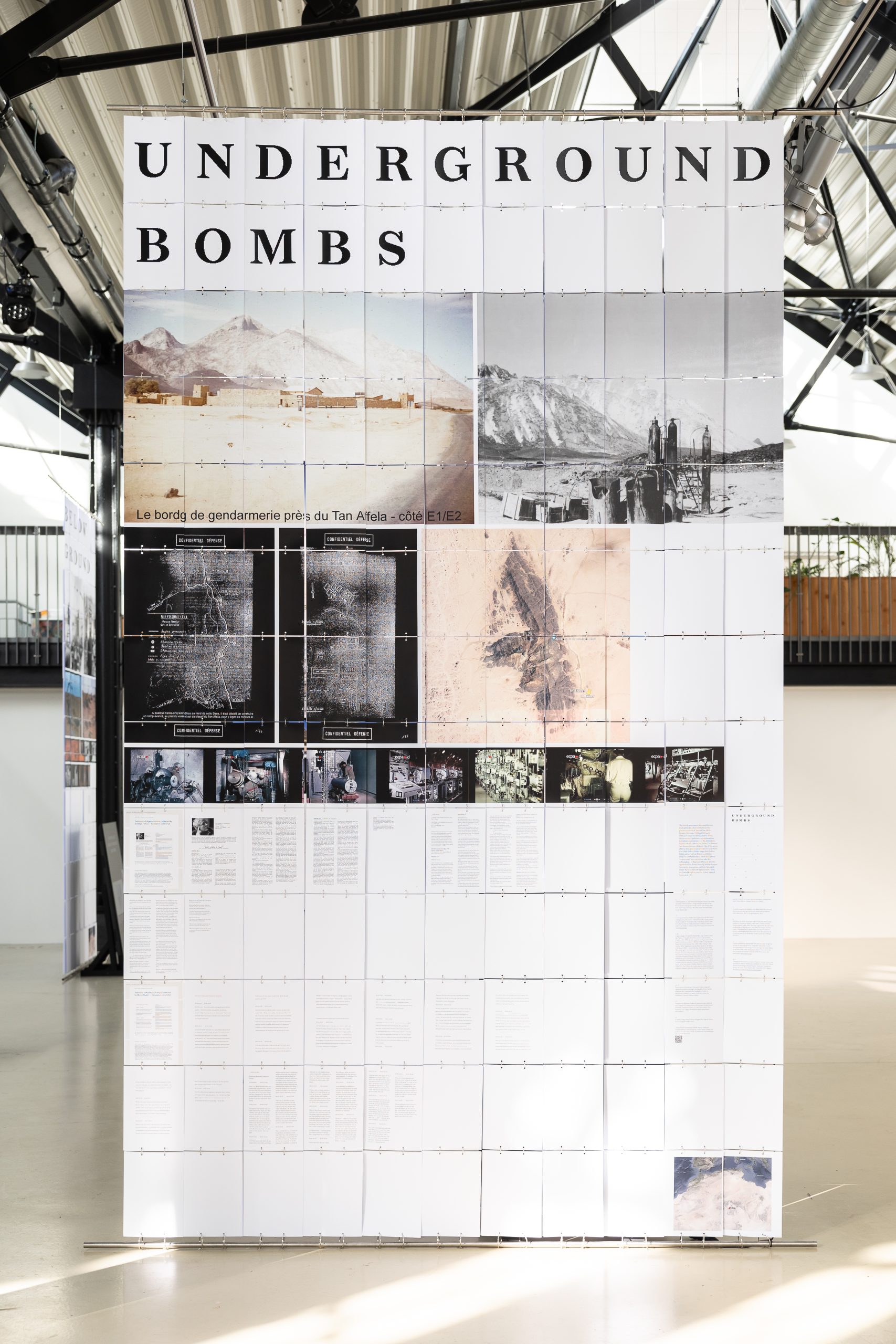

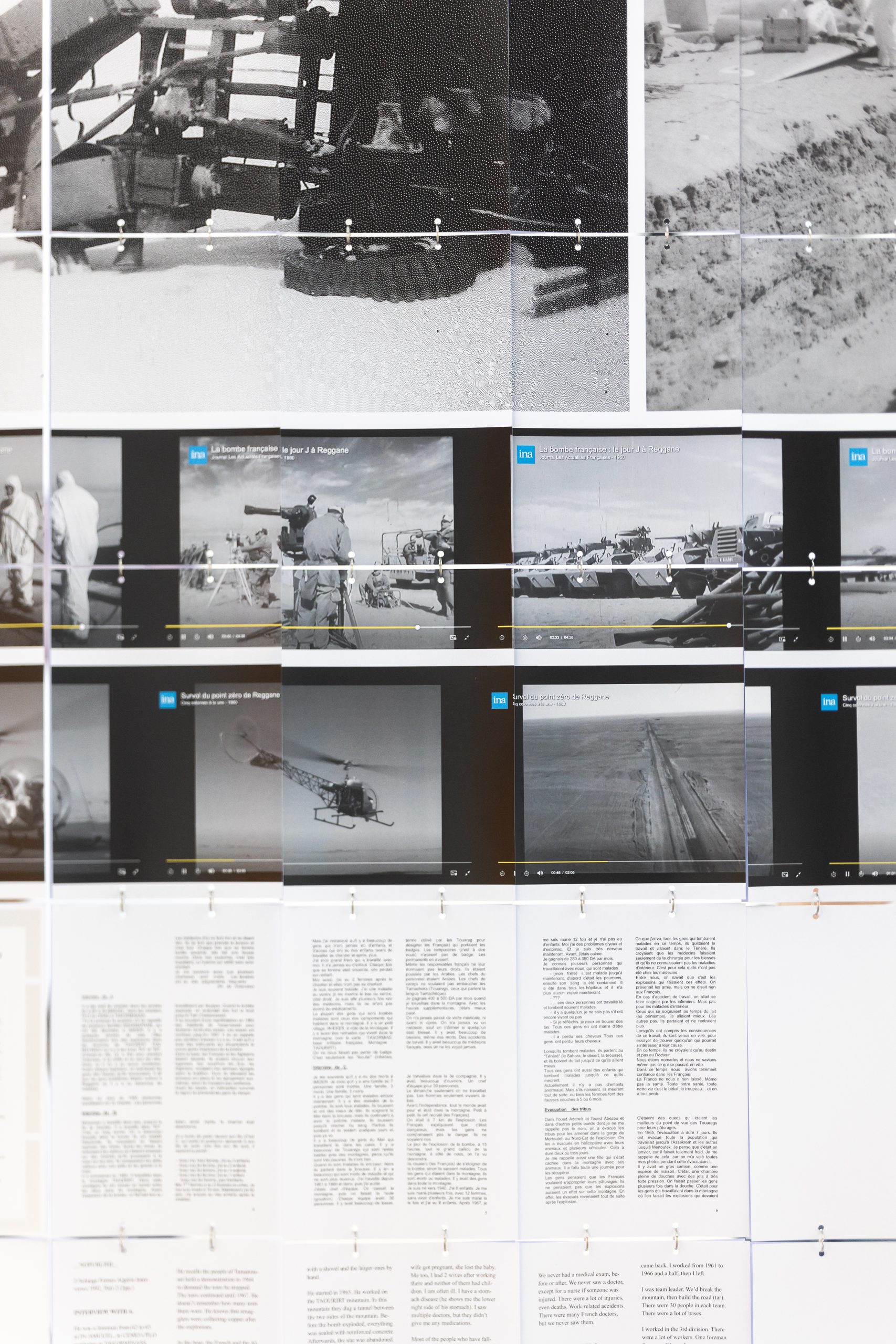

Figure 1. Installation photo of the exhibition Performing Colonial Toxicity (2023) by Samia Henni at Framer Framed in collaboration with If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution, Amsterdam. All photos © Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed.

Like Henni’s previous exhibition, Discreet Violence: Architecture and the French War in Algeria (2018), on the transformation of the Algerian countryside through the construction of French military camps during the Algerian Revolution, this is a presentation of research materials. Consisting of thirteen rectangular, four-meter-high panels, suspended from the roof’s metal trusses and placed perpendicularly across the exhibition hall, the installation is organized thematically, with each panel dedicated to a specific subject, such as “Survivors,” “Exposure,” “Atmospheric Bombs,” or “Below Ground.” Made up of sheets of white A4 sized paper, strung together by metal loose-leaf binder rings, the panels evoke a bureaucratic structure. Photographs, film stills, and other visual materials gathered by Henni and her collaborators are printed on the panels’ upper halves, with the lower areas closer to the viewer reserved for written documentation. But with multiple sheets left empty, the installation also seems to suggest that this is research in progress, and the record incomplete.

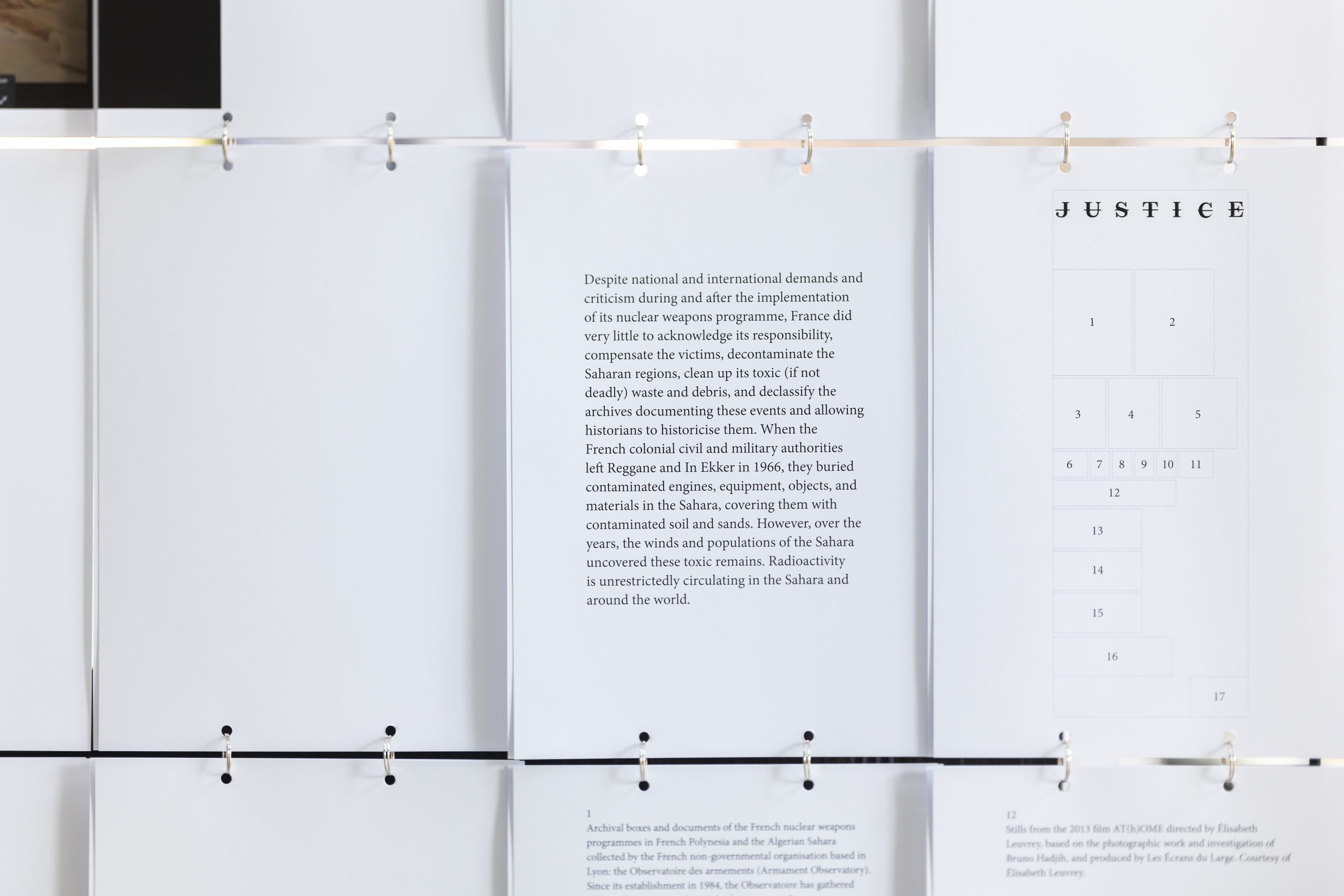

Figure 2. Installation photo of the exhibition Performing Colonial Toxicity (2023) by Samia Henni at Framer Framed in collaboration with If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution, Amsterdam. All photos © Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed.

In earlier writings, such as the editorial of the 2022 publication Deserts Are Not Empty, Henni argued that the prevailing narrative of the desert as a place containing “nothing at all” legitimized its transformation and toxification. It also validated France’s decision to conduct nuclear experiments in the Algerian Sahara. Henni’s exhibition disrupts the platitude of nothingness by rendering the desert as a place full of life, and by underlining that many lives in the Algerian Sahara were upended by the construction of two nuclear testing centers by the French colonial authorities in the desert: one near Reggane, a small town in the Tanezrouft Plain approximately 1,500 kilometers southwest of Algiers, and in In Ekker, about 500 kilometers further south. The first base, called the Centre saharien d’expérimentations militaires (the Saharan Center for Military Experiments), was built for the explosion of atmospheric nuclear bombs in the open air. The second base, the Centre d’expérimentations militaires des oasis (the Center of Military Tests of Oases), functioned as a testing center for underground explosions in the nearby Tan Afella massif. Grainy images of the In Ekker compound, occupying 170,570 hectares, reveal the scale of the infrastructure built by the French colonial authorities: an airbase, a military camp, offices, and long rows of simple, nearly identical prefabricated houses standing in the desert.

Figure 3. Installation photo of the exhibition Performing Colonial Toxicity (2023) by Samia Henni at Framer Framed in collaboration with If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution, Amsterdam. All photos © Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed.

Figure 4. Installation photo of the exhibition Performing Colonial Toxicity (2023) by Samia Henni at Framer Framed in collaboration with If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution, Amsterdam. All photos © Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed.

The austere and minimal display invites the reconstruction of a lost narrative about what happened in the Algerian desert. With no clear starting point or end, visitors are encouraged to meander through the installation while interpreting the “raw” materials on view. Performing Colonial Toxicity transforms the viewer into a researcher, who must read, evaluate, and piece together different types of evidence captured at varying levels of resolution. Assisted only by short introductory texts printed on each panel and brief captions, this is not an easy task, in part because of the amount of information, and in part because most documents, at first glance, look the same. Close reading, however, reveals intriguing yet grim stories. Particularly haunting are the testimonies, such as by Amoud ag Boudjamaaa, born not far from In Ekker, who was eleven when one of the nuclear bombs exploded. He recounts: “When the earth shook, all these mountains and everything else crumbled, we didn’t know that it was dangerous for people… People fell ill, some died, seventeen died. They came down with this illness and they remained ill for a long time until their death, right?” The juxtaposition of the document’s plain typescript and the gravity of its content is jarring. Such descriptions underline the long-lasting impact of radioactive waste but also exemplify Rob Nixon’s claim that environmental harm is a form of “slow violence” most acutely felt among the poor and disempowered.

Figure 5. Installation photo of the exhibition Performing Colonial Toxicity (2023) by Samia Henni at Framer Framed in collaboration with If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution, Amsterdam. All photos © Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed.

Figure 6. Installation photo of the exhibition Performing Colonial Toxicity (2023) by Samia Henni at Framer Framed in collaboration with If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution, Amsterdam. All photos © Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed.

For viewers with some knowledge of France’s colonial occupation of Algeria, or the history of testing nuclear weapons in the Global South, Performing Colonial Toxicity offers a gripping experience. Yet as a freely accessible art space located outside of Amsterdam’s center, Framer Framed attracts a broad audience. Interesting but also helpful supplements to the archival materials are interviews conducted by Henni with several scholars and scientists. Shown on small screens mounted in front of the panels—underlining their separate status as secondary source materials—the videos include Gabrielle Hecht, author of Being Nuclear: Africans and the Global Uranium Trade (2012), who recounts the complexities of doing research on the history of nuclear energy, but also the French physicist Roland Desbordes, director of an independent research organization on radioactivity, who discusses the impact of nuclear materials on the environment. What emerges is a shocking account of colonial violence that continues to this day; heightened radioactivity is still measured in the region, with important environmental, social, and geopolitical consequences. More ancillary materials, for example a timeline of the nuclear experiments in relation to France’s occupation of Algeria, or maps locating the nuclear testing centers within the Algerian Sahara, would have been useful to make this history more easily comprehensible.

Performing Colonial Toxicity puts into focus a trend of the past decade that intersects architecture with related fields of expertise, especially environmental disciplines. More specifically, it underlines the complexity of studying toxicity in the built environment, as discussed in Aggregate’s Toxics project, organized by Meredith TenHoor and Jessica Varner. Through this heap of fragments and snippets, Henni makes something that is intangible and invisible—radioactivity and radioactive fallout—tangible and visible through conscientious research that does not close the case on France’s nuclear experiments but opens it up to further action. As an alternative archival repository, Performing Colonial Toxicity, together with the book and website, will inspire the writing or creation of new work about the violent history of nuclear testing in the Algerian Sahara and beyond. More importantly still, it offers a model for transforming decolonial archival practice into public forms of resistance.

Figure 8. Installation photo of the exhibition Performing Colonial Toxicity (2023) by Samia Henni at Framer Framed in collaboration with If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution, Amsterdam. All photos © Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed.

Rixt Woudstra is an assistant professor of architectural history at the University of Amsterdam and codirector of the Amsterdam Centre for Urban History. Her research focuses on modern architecture, material culture, and colonialism, specifically in West Africa. Her first book, Architecture, Empire, and Trade: The United Africa Company, cowritten with Iain Jackson, Ewan Harrison, Michele Tenzon, and Claire Tunstall, will be published by Bloomsbury this year. She completed her PhD at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.