Museum of Arts and Design (MAD)

New York City.

Labaco has assembled a large exhibit in the small MAD footprint that features more than 100 works by eighty-five artists, architects, and designers from twenty countries, with bias toward New York and London residency. Marquee stars like Zaha Hadid, Ron Arad, Anish Kapoor, and Maya Lin are represented alongside emerging luminaries such as Markus Kayser, Softkill Design, Nervous System, Unfold, and Front Design. The brilliance in the show is generated by this fresh talent. The cross-disciplinary roster displays a robust and critical range of art and design work that is inspiring and challenging. The interactive format of several exhibits and visitor participation in coordinated workshops, educational programs, and a digital design lab offer enticing engagement for a broad audience. On a recent weekend, the majority of visitors appeared to be a cross section of the general public curious about the subject matter and thrilled with the interaction opportunities. Children were the most zealous—the soon-to-be artists and designers who see no barriers between the digits of their hands and the digital tools they play with. As designer-in-residence Lauren Slowik noted, “kids get it.” The show is successful in its attempt to elevate the democratization of art and design and strives to demystify the process of making. Though framed for a layperson, there is ample substance to engage students, academics, and practitioners in art and design disciplines. A stated goal of the exhibit is to “demonstrate the reciprocal relationship between art and technological innovation as well as materials and new techniques,” and a walk through the Out of Hand galleries reveals several projects that demonstrate this with aplomb.

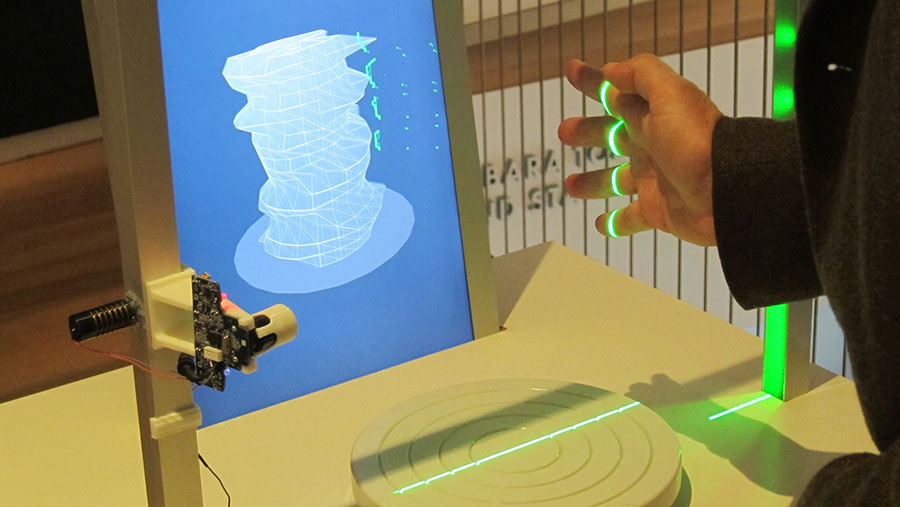

Ascending MAD’s grand staircase to the first exhibit, visitors are greeted by l’Artisan Electronique by Unfold and Tim Knapen, an innovative riff on an age-old process for configuring clay-coil pottery. Sitting down at a digital “potter’s wheel” (comprised of an aluminum-framed laser field hovering over a disk with a viewing monitor displaying a rotating virtual clay cylinder) participants immerse their hands in the field and begin to sculpt a virtual vessel in real time. An array of fifteen digital monitors on the wall load each completed iteration in sequence, recording time and day of creation. A digital 3-D printer dispersing coils of clay is poised nearby for immediate transformation of the virtual to corporeal. A clear vitrine on a black background suspends bespoke vases of white porcelain as proof of concept and turnkey production. The project expands creative potential by setting productive limits on the tools of production and streamlining material flow. Curiously, the hardware and software transform the fine precision of the hand into a blunt instrument and the diminished sensation of touch reduces the prime feedback sensation for potters. The sanitized process takes the fun out of making a mess, though further development could lead to new form-finding and resource optimization. Strategically sited as the gateway to the show, l’Artisan Electronique delivers on Labaco’s promise that “changes in practice, products, and purpose provoked by digital technologies are inevitable, evolving, and exciting.”

Walk a few steps farther into the gallery and Solar Sinter, a simple and brilliant work by a young graduate of the Royal College of Art named Markus Kayser, appears. This experimental project uses sunlight and sand as raw energy and material to produce glass objects in situ. Presented primarily in a Sundance-worthy video production, the entire process of hauling a portable PV-powered fabrication studio complete with Fresnel lens, CNC laser-sinter, and 3-D printer into the Sahara at dawn, producing objects from the sand below with the concentrated light from the sun above, and breaking camp at dusk is concise, complex, and breathtaking. In the author’s words the project “aims to raise questions about the future of manufacturing and triggers dreams of the full utilization of the production potential of the world’s most efficient energy resource—the sun. The proposition of ‘desert manufacturing,’ of using what is there already in abundance in terms of energy and material, seems like a logical step rather than an eco-friendly version of something else.” His desire to fuse human technology with natural availabilities in an authentic and sustainable union offers a practical, poetic, and ethical model for emulation.

Directly across from Solar Sinter is Protohouse 1.0: Prototype for a 3D Printed House developed by Softkill Design and fabricated in nylon laid down by selective laser sintering and presented as a 1:33 scale model. This protean fabrication appears as the cantilevered skull of a dinosaur with a staircase climbing the jawbone and a male figure in the maw for scale. The house model is comprised of 30 fibrous “micro-organized” bony components that configure structure, enclosure, furniture, and stairs. The techno-romantic work is a prelude to Protohouse 2.0, currently in development by the designers with ambition to be the first house fabricated solely through 3-D printing. Houses of the future will likely be fabricated with tools analogous to 3-D printing. The Softkill experiment blazes a new trail for building morphology, tools of production, and poetic expression. However, architects and prospective homeowners may not be ready to walk down this path today. Visions of future building will not likely appear in the form of extinct animals.

Moving one floor up, work presented by Achim Menges and Jan Knippers appears in video clips documenting two ICD/ITKE Research Pavilions. The first experimental structure was designed and fabricated in 2011 in collaboration with students from the University of Stuttgart. The architecture is based on morphological principles of the sand dollar (subspecies ofEchinoidea), which exhibits a modular system of polygonal plates joined by finger-like protrusions. The pavilion translates these principles into a series of prefabricated plywood panels finger-joined at the nexus of three panel edges to define articulate space and form. This morphological innovation extends the field of geometric expression beyond load-optimized geometries typically required for lightweight construction, specifically when utilizing stressed-skin sheet material. The second structure was developed in 2012 in collaboration with students and biologists to extend the morphological principles of arthropodan exoskeletons like that of a lobster. Employing carbon and glass fiber with a digital weaving robot, the team developed an isotropic fiber structure that strategically distributes forces through material differentiation and orientation. Digital design tools made the material and structural analysis possible, and the multiaxis knitting machine made fabrication possible. For both pavilions the digital process of design, fabrication, erection, and occupation is eloquently captured in the project video. The work demonstrates great integrity through contextual reference and clearly revealed process. As an exhibit, however, the presentation format is underwhelming. A small monitor projects videos that have been available online since the pavilions were constructed. A large and immersive display animated with the sounds of production would bring the projects to life in a richer way.

Nearby, two works that also explore force and resultant are Vase #44 and KiLight by young Parisian designer Francois Brument with engineer Sonia Laugier. They each transform air, movement, and voice into form and space through a sound-to-volume algorithm and Microsoft Kinect device. An infinite range of vessel designs and light fixtures are displayed, and the generative process is demonstrated through digital sensors and tools in the exhibit. In the ultimate “hands-free” work of design, the ability to use one’s voice or hand gestures to create new 3-D objects through modulation alone is remarkable. It is as if the senses of sound and touch merge synthetically as a meta-sense in the service of new process, discovery, and expression. The potential for acoustics to profoundly influence spatial configurations and become a prime driver for design is anticipated by this work.

Also on this floor is an intelligent and humorous work entitled Chairgenetics by Jan Habraken from the Netherlands, now working in New York City. As an experiment, the author asks, “What if we can apply the science of genetic engineering to an inanimate object?” His project explores the “cross-breeding” of individual chairs, both vernacular and historical, in the search to find the ultimate chair. Data on preferential chair traits and characteristics were compiled through Google and Yahoo rankings. New 3-D software called Symvol was utilized to morph the chair lineage, which is presented as a 3-D family tree of scale models developed through digital modeling, 3D printing, selective laser sintering, and stereolithography. The project demonstrates the kind of “family” relationships all designers contemplate when developing a work of design. At the end of the line is a full-size Frankenstein offspring only a mother could love, but the process of transformation is outlined clearly, the pedigree is transparent, and the potential for future application in art, design, and architecture is promising.

All of the projects described above reveal perhaps the simplest and most important role for digital tools as productive extension of all the sensory organs of the human body, including the mind, which, as Louis Sullivan once noted, is just “the most exalted of senses.” Other noteworthy projects in the show that reach this level of sensory engagement include Hiroshi Sugimoto’s sublime Mathematical Model 009, Chuck Close’s historical and ethereal Self-Portrait/Five Part digital Jacquard tapestry (a Jacquard loom head being an early precedent to the punch-card computer and CNC tools), Carballo-Farman’s powerful Object Breast Cancer, Scott Summit’s Bespoke Fairings, and Daan Van Den Berg’s hilariously transgressive Merrick Lamp. This lamp is the result of nefariously infecting Ikea CAD files with an “Elephantiasis virus” that only appears as customers print their Ikea product at home on their 3-D printer and find strange deformities on their new luminaire. These works all leverage sensory perception and go beyond the merely decorative as they form fresh and meaningful connections to ecology or commerce, history or health, biology or mathematics. The authors are able to step outside themselves and beyond themselves as they make life more vivid through their work. They employ digital technology in unique ways to produce outcomes that could not be realized in any other way. The best works establish a productive synthesis of technology, process, and expression to pose questions and explore outcomes.

Disappointing is the apparent lack of questioning and exploration in much of the work exhibited by artists and designers with broader name recognition. Though all their work meets a requisite standard of decorative beauty for a museum setting, much of it seems to lack the contextual vibrancy and broader relevancy of the youthful works cited above. Creativity seems mostly gauged by a barometer of difference, myopia, or excess. Often the role of the digital appears as a tack-on to something that could easily have been conceived and executed through nondigital thinking and making. Like decorative masks concealing any countenance of ecology or purpose, the projects employ bio-mockery, or specious chemicals, or precious materials, or expensive processes. In an age of digitally verified provenance, we should be tracking blood diamonds harvested and fossil fuel extracted as we create or enjoy our pleasures. I am sure human desire will always demand $50,000 coffee tables, custom floral silverware, bespoke dressing gowns, jewel-encrusted neckwear, and perhaps concrete houses on the moon (where does the water come from?), but I believe 99% of us won’t want or need these things in our dreams or our futures. We should demand more from gifts of talent or experience and expect museums to broaden their ethical field of view.

Also frustrating is the forced categorization of the exhibition work into a smorgasbord of six themes noted as Modeling Nature, New Geometries, Rebooting Revivals, Remixing the Figure, Pattern as Structure, and Processuality. This seems at odds with the cross-disciplinary intentions of the curation and the observation that most of the works could easily fit into two or more thematic categories. Emerging artists and designers today are defying traditional categories with their hybrid work and process. The accompanying catalog, beautifully designed and produced by Black Dog Publishing, exacerbates the thematic problem by displaying mostly outcomes and not enough process.

Out of Hand claims to be the first “in-depth survey dedicated to exploring the impact of computer-assisted methods of production on contemporary art, architecture and design,” though much of the work in the show has been displayed elsewhere. The Museum of Modern Art’s 2008 Design and the Elastic Mind addressed similar issues with similar outcomes. Most works have been online in a variety of digital venues prior to the show, and numerous print publications have addressed the theme in the last decade. With the dominance of near-instant digital communication around the world, the ability to be first in anything is becoming more difficult and perhaps less relevant. Being able to do something meaningful and remarkable is perhaps becoming more difficult and also more important. It is curious why the secondary title Materializing the Postdigital is proffered when most of the digital tools employed to create works in the show are just beginning to demonstrate some potential and viable application. “Neodigital” might better describe the powerfully emergent and naive tools currently put to work, if they really need to be named at all. One thing seems clear: the Digital Revolution is transforming into the Digital Vernacular.

The exhibition raises many more questions than are answered by the work displayed, and also by the title. What is meant by the expression “out of hand”? Given MAD’s craft and curatorial history, out of hand must refer to the work that emerges from the hand of the artist or designer. Some of the work on display meets this threshold of entry, though most of the work is clearly crafted by other and many hands and is therefore out of hand. Does the title refer to digital media and production transcending or usurping the hand of the maker? Several works demonstrate this occurrence. Does the title refer to things being out of control or produced without taking enough time to think? Some works also reveal this unfortunate condition.

Thomas Princen, writing in The Logic of Sufficiency, states that if humans are to be in equilibrium with the earth and life in all its forms we have to know how much is too much, how much is not enough, and how much is just right. Clearly not a reductionist principle, Princen’s admonition compels us to think holistically about what is fundamentally important to life and our expression of it through works of art and design. In The Nature and Aesthetics of Design the author David Pye notes that “Design, like war, is an uncertain trade, and we have to make the things we have designed before we can find out whether our assumptions are right or wrong. Research is very often a euphemism for trying the wrong ways first, as we all must do.” The exhibition Out of Hand is to be commended for putting up works of the world for all to witness, and the exhibitors appreciated for having the courage to try things out.