REVIEW

BOOK EDITED BY MICHAEL SORKIN AND DEEN SHARP

AUC PRESS, 2021

June 21, 2024

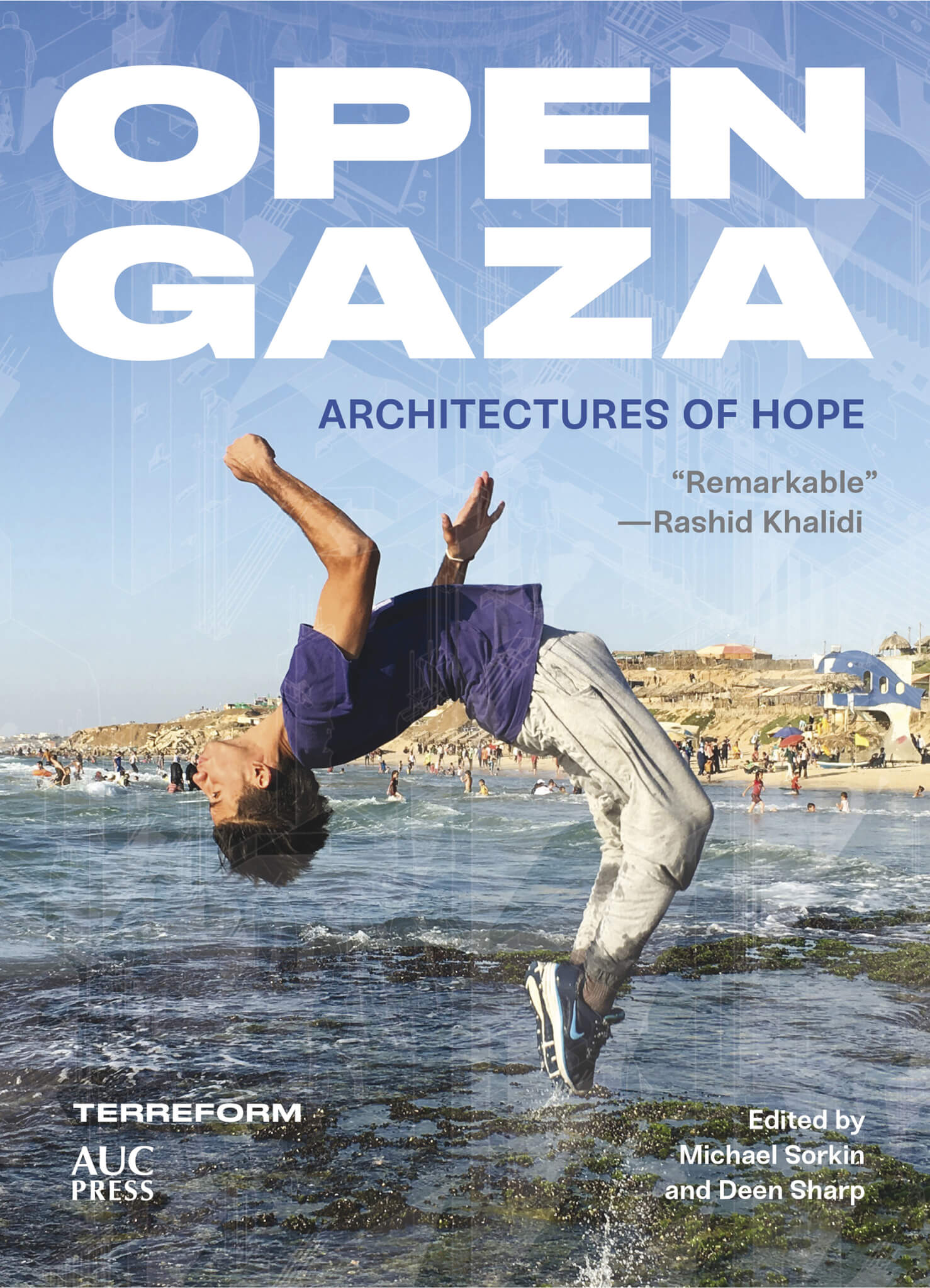

At a time when Gaza is subjected to an unrelenting Israeli military campaign and forced starvation, and when the International Court of Justice has ruled Israel’s war aims violate Palestinian rights under the Genocide Convention, you would be forgiven for not turning to a book on architecture to learn about Gaza. Still, I recommend Open Gaza to JAE readers as a means of considering the role of architecture and design professionals relative to these events and their aftermaths. Borne out of the editors’ anguish during another major assault—the horrific events of Operation Protective Edge in 2014, itself just one of several such assaults in past decades—this volume offers a powerful and engaging, yet approachable, entry point into the subject, especially for students.

Open Gaza is a large-format, 340-page volume, edited by architect and critic Michael Sorkin (who passed away in 2020) and geographer Deen Sharp, both of the nonprofit urban research studio and advocacy group Terreform. It includes twenty-one contributions spanning theoretical essays, descriptions of built work and site analysis, speculative design explorations, and graphic narratives/infographics. While the information will be familiar to those invested in scholarship on the region, the book has an incredible thematic range, moving from political histories to planning and legislative analyses, personal narratives, and design proposals. According to the editors, contributing authors “engage Gaza beyond the malign logic of bombing and blockade. They consider how life could be improved in Gaza within the limitations imposed by Israeli malevolence but also reach beyond this framework of endless war to imagine Gaza in a future without conflict” (11–12). At present, this ambition seems removed from the most pressing on-the-ground realities. Yet there is value in widening our gaze—historically, politically, and geographically—beyond the current violence and humanitarian crisis to more expansive views, and there is much to be gleaned from the volume in this regard. Authors cover both the close-up material scale and the zoomed-out geopolitical context.

Open Gaza sits easily within the past two decades’ trend of mapping and countermapping as a means of spatial agency. It includes chapters by Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman, Malkit Shoshan, and Rafi Segal, scholars well known for such work. Several authors cover the fraught role of our profession in local planning and development. They probe the power of cartography and visual communication to define and delimit Gaza, arguing that we need to better historicize contemporary events and challenge a denial of Palestinian territorial contiguity—or inversely, the framing of the Gaza Strip as a remote, bounded entity. Mahdi Sabbagh and Meghan McAllister’s chapter “Timeless Gaza” is especially good on this front, demonstrating how “the map can be used as both a weapon of colonization and an object capable of influencing a more equitable future” (91). Likewise, Yara Sharif and Nasser Golzari’s “Absurd-city, Subver-city” delivers compelling engagement with the politics of mapping and representation. They bring together critical theory and design to argue for our discipline’s power to speculate, propose, and elucidate—captured in what they term “Moments of Possibilities” (97). Themes here follow Sharif’s earlier book Architecture of Resistance: Searching for Spaces of Possibilities under the Palestinian/Israeli Conflict (2017). M. Christine Boyer’s chapter “Planning Ruination” in turn gives a pointed historical synopsis communicating complexity and nuance to a nonexpert audience.

Helga Tawil-Souri’s brilliant chapter “The Internet Pigeon Network” (158) is another thoughtful contribution bridging theory and speculation. She proposes using homing pigeons to provide Gaza with a self-reliant, Israel-free means of plugging into the global information network. The ingenuity of the proposition and its rootedness in Gaza’s history restored my faith that there can be local design agency, particularly through interdisciplinary approaches where sociopolitical justice is integrally linked to environmental and technological justice. The essay nicely complements Tawil-Souri’s broader scholarship on the politics of technology, media, and culture in Israel-Palestine, including her coedited book Gaza as Metaphor (2016).

Still, some chapters which include speculative design could be better developed and theorized to unpack their vague, abstract, and lofty imaginaries. For example, Craig Konyk’s “City of Crystal” proposes damaged city districts be rebuilt entirely out of glass and covered by enormous glass domes until all of Gaza is “transformed into a massive crystalline urban structure” (229), putting destruction and fragility on display, and “symbolizing a more open and progressive future” (231), yet saying little about daily life or inhabitability. In “Solar Dome” Chris Mackey and Rafi Segal propose an extensive solar panel network on underutilized rooftops and within the existing tightly controlled buffer zone between Gaza and Israel. In both chapters, the speculations leave many complex questions unexamined. As a pragmatic gripe, I also found the book’s sequencing not fully intuitive, and I could easily imagine a structure in which contributions better build off one another. For example, anthropologist Hadeel Assali’s thought-provoking theoretical contribution “Hyper–Present Absence: Suggested Methods,” arguing for scholarship on Gaza to break from the dominance of a conflict and humanitarian focus, comes last, when for me at least it establishes a framework for other essays.

Overall, the work left me asking: what are the roles of the design fields in Palestine and in the push for justice for Palestinians? Architects, urbanists, and scholars have long engaged critically with the spatial politics of settler-colonialism, military occupation, and humanitarian intervention, particularly in this region. Open Gaza, too, builds off earlier work, reassembling select scholars from Sorkin’s edited volumes The Next Jerusalem: Sharing the Divided City (2002) and Against the Wall: Israeli’s Barrier to Peace (2005). The editors of Open Gaza concede that the arguments made in these previous volumes have gone unheeded and that the oppression they described has intensified (13). Yet architectures of hope are important, so how can the design professions affect change? As with many design-research publications attempting to engage with the world’s most pressing problems, Open Gaza suggests multiple openings then left for others to further unpack and elucidate beyond this volume. In this sense, the book serves as a promising catalyst for new work, optimism, and discussion: an opportunity to push the design disciplines toward greater knowledge, accountability, and action.

Suzanne Harris-Brandts, PhD, OAA, is an assistant professor of architecture and urbanism at Carleton University. She is cofounder of Collective Domain, a practice for spatial analysis, urban activism, architecture, and media in the public interest, and a former architect in residence at DAAR—Decolonizing Architecture Art Research—in Battir and Beit Sahour, Palestine. Her research brings together design and the social sciences to explore issues of power, equity, and collective identity in the built environment. Harris-Brandts holds a PhD in Urban and Regional Planning from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and is licensed with the Ontario Association of Architects (OAA).