REVIEW

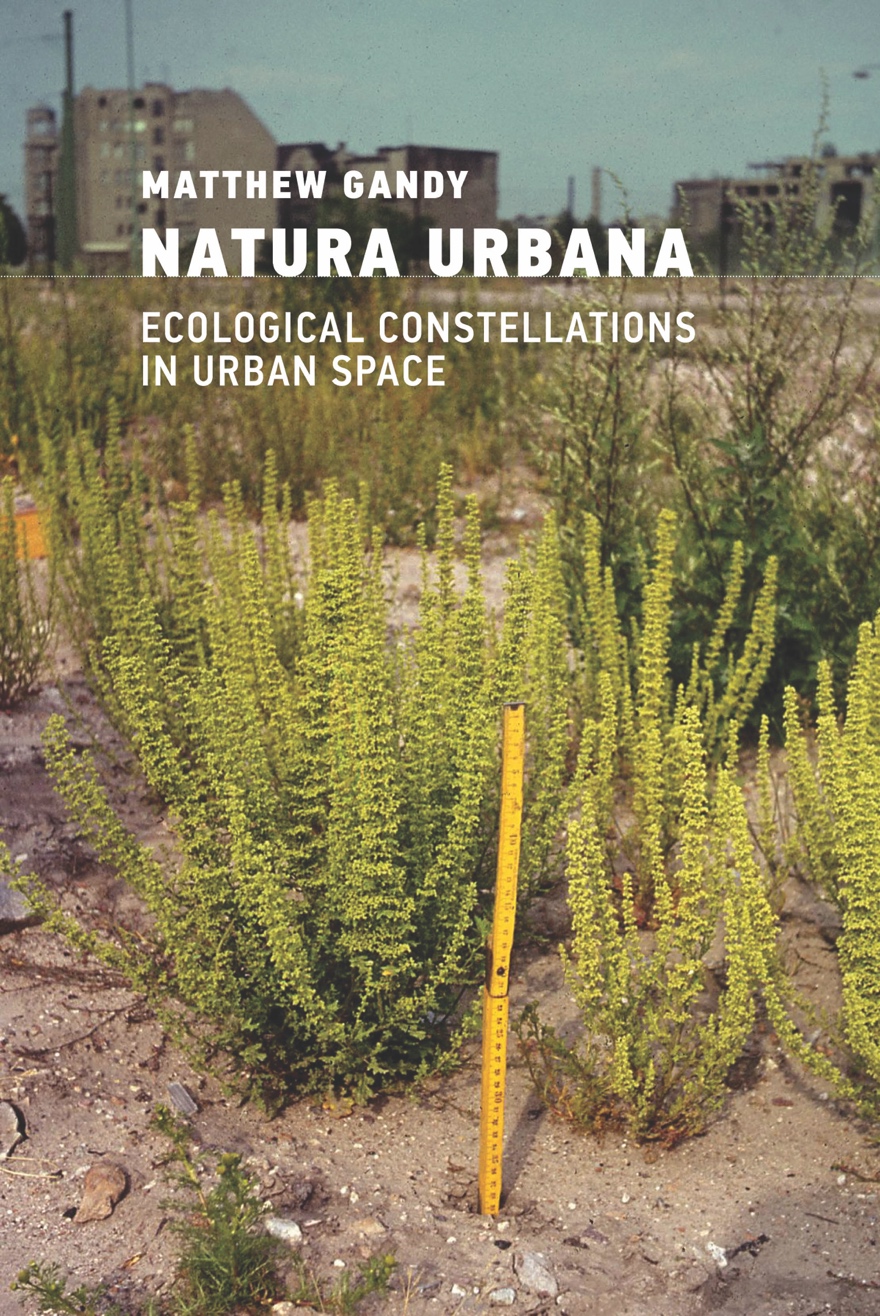

MATTHEW GANDY

MIT PRESS, 2022

May 24, 2024

Geographer and urbanist Matthew Gandy’s most recent book, Natura Urbana, masterfully explores questions that consider whether urban nature is “nature.” He leads readers through the complex interactions between life forms on this planet, centering humans as he uncovers socio-political, cultural, and ethical entanglements. Gandy’s work on urbanism has focused on the connection between sociopolitical systems and the earthen-systems they rely on (see The Fabric of Space: Water, Modernity, and the Urban Imagination, MIT Press, 2017, and Concrete and Clay: Reworking Nature in New York City, MIT Press, 2003). This book extends these concepts into a deep exploration of how nature and urban environments interface, highlighting that humans are both reliant on, subjected to, and participants in the independent dynamics of nature’s agency.

I read Natura Urbana in July 2023, the hottest month ever recorded on planet Earth. The oceans are warmer than ever, and the planetary changes that have been anticipated for decades are happening faster than predicted. Secondary and tertiary unpredictable disasters are becoming the norm. The book has caused me to pause and hold two potentially opposing thoughts together. On the one hand, the novelty of ecosystems within urban environments is critical and fascinating. Urban environments have led to new mixes of species that have never before shared the same spaces. On the other hand, I am also cautious about romanticizing the great ecological experiments of urban built environments. I am concerned about the impacts of overextraction and reliance on peripheral landscapes that feed the continuous construction and deconstruction of cities. The disregard for life beyond the city is an ethical crisis.

Gandy explores his questions through the skillful synthesis of philosophical and conceptual ideas from dozens of authors, modes of thought, and disciplines across time that are rooted in, adjacent to, or influence the field of urban ecology and human understandings of nature. He extends the work of authors such as environmental historian William Cronon and anthropologist Anna Tsing in demonstrating that culturally conditioned perceptions of nature and the environment influence how human individuals and communities interact with it. While at times Gandy writes for highly experienced readers, his use of examples and story-telling remedies abstractions. He provides grounded, tangible occurrences of theoretical ideas from both real-world precedents and imaginaries explored in science fiction, art, and film to describe a variety of ecologies that emerge in a range of urban environments. The complexity and richness of Gandy’s writing combined with the context and mindset with which a reader might encounter this text is important; it will influence the trailing thoughts that emerge, and the synthetic connections a reader will make between Gandy’s descriptions and their own lived experiences.

Chapter 1, “Zoöpolis Redux,” explores the relationship between humans, animals, and other more-than-human beings. Gandy describes how urban environments, influenced by a variety of factors including conservation efforts, animal and insect adaptations, and the emergence of spontaneous vegetation in disturbed and/or abandoned landscapes, are contributing to a rewilding of urban areas, a process coupled with a reenchantment of the experience of nature within the city. He describes how coyotes are becoming a symbol for cosmopolitan ecological imaginaries as well as an indicator for the untamed more-than-human landscape within controlled elements of the metropolis. Coincidentally, the same day I read this chapter I encountered two coyotes in the morning calmly navigating the quiet, winding streets of southwest Portland, Oregon, as dogs barked at them, and watched four fledging Cooper’s hawks in the afternoon taking a dust bath 10–15 feet away. In both instances the animals were unbothered by human presence, and I experienced first-hand how animals have behaviorally evolved to inhabit and rely on human-dominated landscapes—a phenomenon Gandy uncovers throughout the book. Are such ecological adaptations to urban environments another form of domestication, or a rewilding of human-dominated environments?

By centering the discussion on urban wildlands as sites that contain novel ecosystems, the book questions, critiques, and expands notions of “nature” and “wildness” that are often seen as existing on urban peripheries and external, and at times antithetical, to urbanization. Understanding urban wildlands as a hybrid condition presents opportunities to create alternatives to conventional and hegemonic scientific practices and framings of ecologies. As Gandy demonstrates, concepts, perceptions, and sociopolitical constructs of urban nature are complex and nuanced. He reminds us that landscapes, including parks, are sociopolitical reflections of evolving cultural attitudes toward nature, wilderness, and ecologies, including debates between native versus nonnative inhabitants. Through this discussion, he consistently questions what the benchmark is for nativist arguments and how such arguments correlate with nationalism and racism toward immigrant (or “nonnative”) populations. Similar attitudes are often applied to wastelands, as they demonstrate a confluence of the unintentional; it is where the consequences of human activities interface with the unpredictability of nature. Wastelands are registrations of human-nature dynamics.

As Gandy concludes, he describes how the COVID-19 pandemic afforded opportunities for urban dwellers to reconnect with their natural environments. He emphasizes the importance of sensory contact with nature as critical to maintain connection to place and, I would argue, place attachment, which can drive empathetic relations with the more-than-human world. In order to shift away from generic, universalist assumptions of singular ecologies, he describes a pluralism of sociopolitical and cultural constructions of urban ecologies. He advocates for the use of specificities provided by multiple descriptions of urban ecosystems that embrace their differences and complexities. The stories that Gandy shares demonstrate exchanges in adaptation, from more-than-humans adapting to human influences, to the need for humans and urban environments to adapt to the changes they themselves have initiated. A “new ethics of interdependence” (204) is one that acknowledges an exchange of coexistences that influence and impact one another, shifting from totalizing systems-thinking to relationally nuanced exchanges, embracing the certainty of coadaptations and coevolutions in this expansive experiment.

Catherine De Almeida is an associate professor of landscape architecture at the University of Washington. Her design research, landscape lifecycles, applies material, social, ecological, and economic life-cycle lenses to the understanding and design of waste landscapes. Her work emphasizes waste relations to illuminate the performance, visibility, citizenships, emotions, perceptions, attitudes, and injustices of waste materials and landscapes.