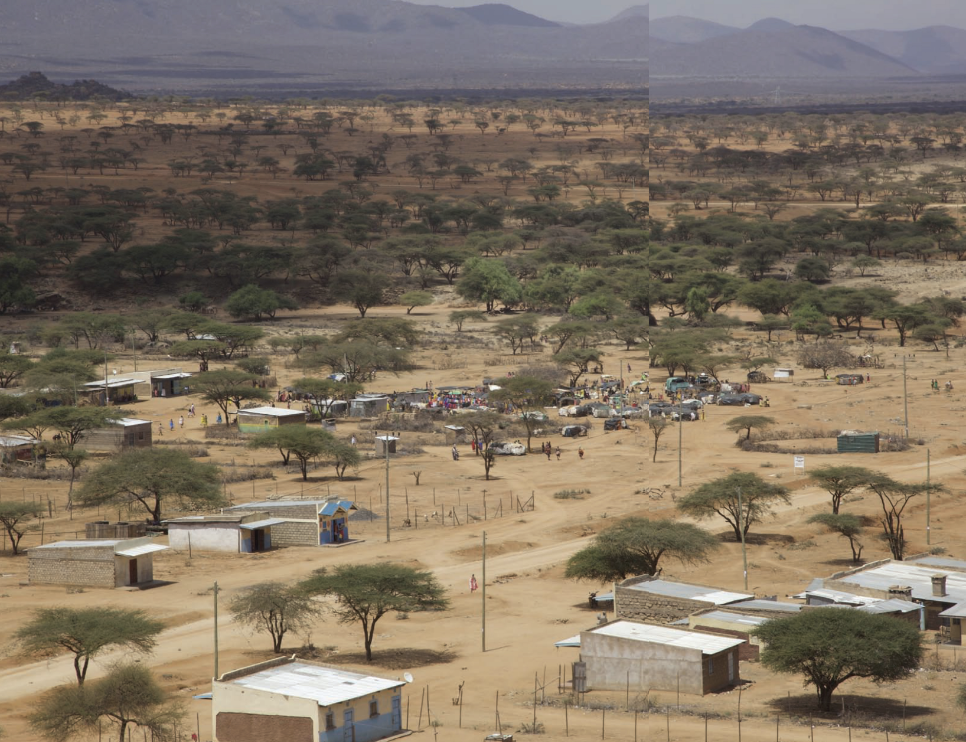

To a newcomer, Samburu, northern Kenya, may first appear as a vast, uninhabited landscape—a reddish, arid flatland punctuated by umbrella acacia trees. The vistas are expansive, occasionally terminating abruptly in a distant peak or serrated range. Assumptions of remoteness are misleading. This terrain, although far from Kenya’s metropolitan centers, is not empty. The Samburu people inhabit this landscape, relying on material and rhythms that blend texturally and tonally into this rich flatland. As external visions recalibrate to this reality, the signs of Samburu settlements—manyatta—and their associated dwellings are seen everywhere. This reorientation to Samburu architecture reveals other relationships and tracings between the unbuilt spaces adjacent to houses, manyattas, routeways and seasonal tracts that lace through the landscape. These all have their own dimensionality and order but are seldom included in conventional plans and cartographic maps. This narrative considers other ways of knowing a landscape through its relationships with people, animals, and the use of built and unbuilt spaces. It presents a case study into a pedagogical project that began as an investigation into teaching climate change but resulted in a reappraisal of how we perceive the invisibilities and contradictions of a desert community.

Continue reading: