August 24, 2013-November 17, 2013

Michael C. Carlos Museum

Antichità, Teatro, Magnificenza: Renaissance and Baroque Images of Rome and Conserving the Memory: The Fratelli Alinari Photographs of Rome

As legend has it, Romulus and Remus, twin sons of Mars, the god of war, founded Rome. Left to drown in a basket on the Tiber by a king of nearby Alba Longa and rescued by a she-wolf, the twins lived to defeat that king and found their own city on the river’s banks in 753 BC. After killing his brother, Romulus became the first king of Rome, which is named for him. Whether mythological or factual, fascination with Rome is as eternal as the city itself.

Antichità, Teatro, Magnificenza: Renaissance and Baroque Images of Rome, composed of maps and prints selected by curators Sarah McPhee, the Winship Distinguished Research Professor of Art and Architectural History at Emory University, and Margaret Shufeldt, former Carlos Museum curator of works on paper, clearly covers both the eras and the medium of printmaking. Over 130 works of art representing ancient Rome, many from the Carlos Museum’s permanent collection, were showcased in three major sections—Antichita, Teatro, and Magnificenza (Figure 1).

Antichita includes the Antiquae urbis imago, Pirro Ligorio’s 1561 reconstruction of the ancient city as the focal point of the antiquarian interests during the Italian Renaissance of the sixteenth century (Figure 1). Ligorio’s reconstruction is surrounded by works by Hieronymous Cock, several others from the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae (Mirror of the Magnificence of Rome), a Renaissance “coffee-table book” of prints of the sights of Rome produced by the French print seller and publisher Antonio Lafreri (1512–77), and images of the obelisks moved by Sixtus V.

The hand-engraved and etched coffee-table books made up about a third of the show and were to me an incredibly eye-opening look at seeing a book as a work of art in and of itself. The historic volumes were from rare and oftentimes oversized book collections, includingDe ludis circensibus by Onophrio Panvinio. Rather than the fast-paced information age we are accustomed to today, these images painstakingly show the importance that classical antiquity and the ancient world had during the Renaissance by poetically documenting history and recording culture.

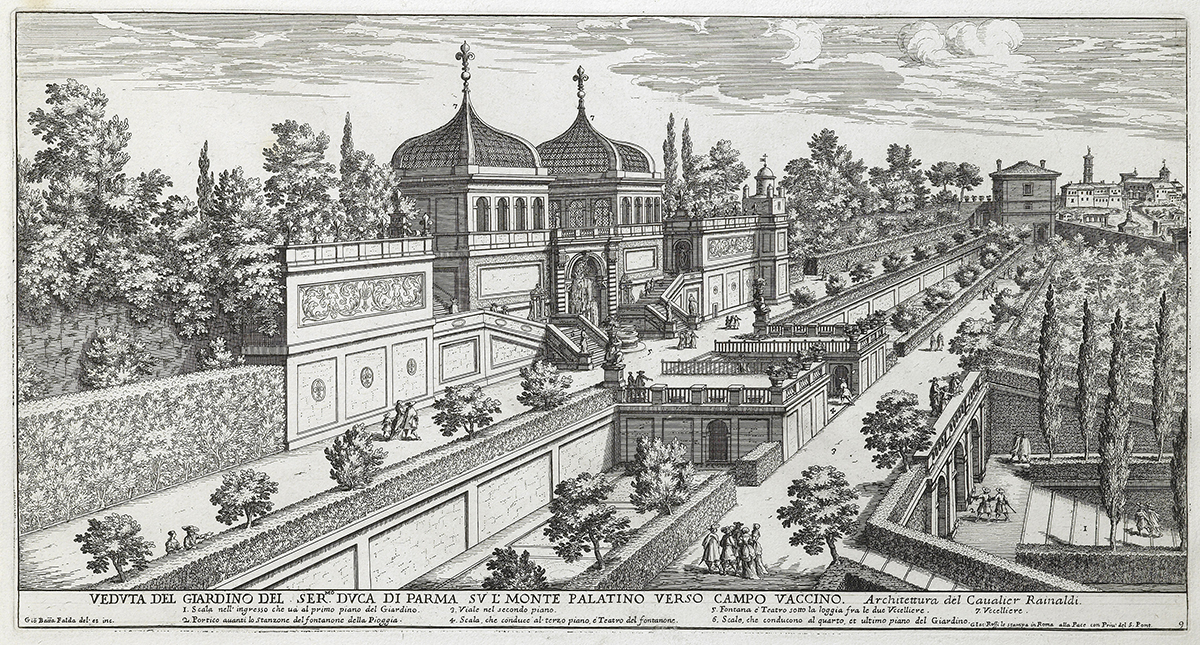

The Magnificenza, or magnificence of the new Rome, as pictured in Giovanni Batista Falda’s monumental and elaborate 1676 bird’s-eye-view map, became an attraction on the Grand Tour taken by young European gentlemen wishing to receive an education in tasteful aesthetics before taking up the tasks befitting their elevated social station. Thus the eighteenth century finds Rome’s printmakers, such as Giuseppe Vasi, producing elegant souvenir images of the city’s most memorable buildings, in etchings that are well represented in this exhibition.

From an imaginary designer’s point-of-view, the impact of Rome in the mid-1700s would seem both exhilarating and frustrating. On the one hand there was the unlimited visual drama of a city, whereas, in contrast, there was a clear medieval orthogonal grid structure with its network of narrow streets traversed by a baroque system of grand processional routes punctuated by fountains, obelisks, and large churches. Depicted are apparent contrasts in scale that were also exploited by large monuments of antiquity like the ceremonial spaces of the Piazza Navona (Figure 3). The exhibit successfully shows works that clearly target not just pilgrims working through the obligatory sites of Rome but aristocrats and intellectuals on the Grand Tour for purposes of cultural rather than religious enlightenment (Figure 3).

The most widely viewed work in the exhibition is Piranesi’s 1762 map of the Campo Marzio. Though based on the newest archaeological evidence of his day, it conflates successive eras of construction into an intoxicating overlay of impossible architectural splendors. In this section there are three different types of representations of the magnificence of the Eternal City by three different designers. Nolli’s map is an example of the rational, scientific thinking of the Enlightenment. Vasi follows in Falda’s footsteps making an encyclopedic collection of views of contemporary Rome. Piranesi takes an archaeological interest in the city and creates strikingly dramatic, imaginative views of the ancient monuments (Figure 4). Visitors to Rome on the Grand Tour purchased these prints as mementos of their sojourn and as evidence of their own learned interests (Figure 4).

The Alinari photographs were distinctly marked by their descriptive clarity, which allowed for the historical preservation of the works that they photographed. Well-known art critic Ernest Lacan remarked of his friends the Alinari brothers, “the Alinari are not content to present the monuments of their country; they have devoted themselves to ‘conserving’ the memory for the future of the masterpieces … that time gradually destroys.” While pictorial preservation was key to their approach, the Alinaris sought to provide distant viewers “truth without interpretation,” and many of their photographs are, like the objects they captured, impressive works of art (Figure 7).

The Alinari photographs were distinctly marked by their descriptive clarity, which allowed for the historical preservation of the works that they photographed. Well-known art critic Ernest Lacan remarked of his friends the Alinari brothers, “the Alinari are not content to present the monuments of their country; they have devoted themselves to ‘conserving’ the memory for the future of the masterpieces … that time gradually destroys.” While pictorial preservation was key to their approach, the Alinaris sought to provide distant viewers “truth without interpretation,” and many of their photographs are, like the objects they captured, impressive works of art (Figure 7).