Lola Sheppard and Mason White, editors and authors

Actar, 2017

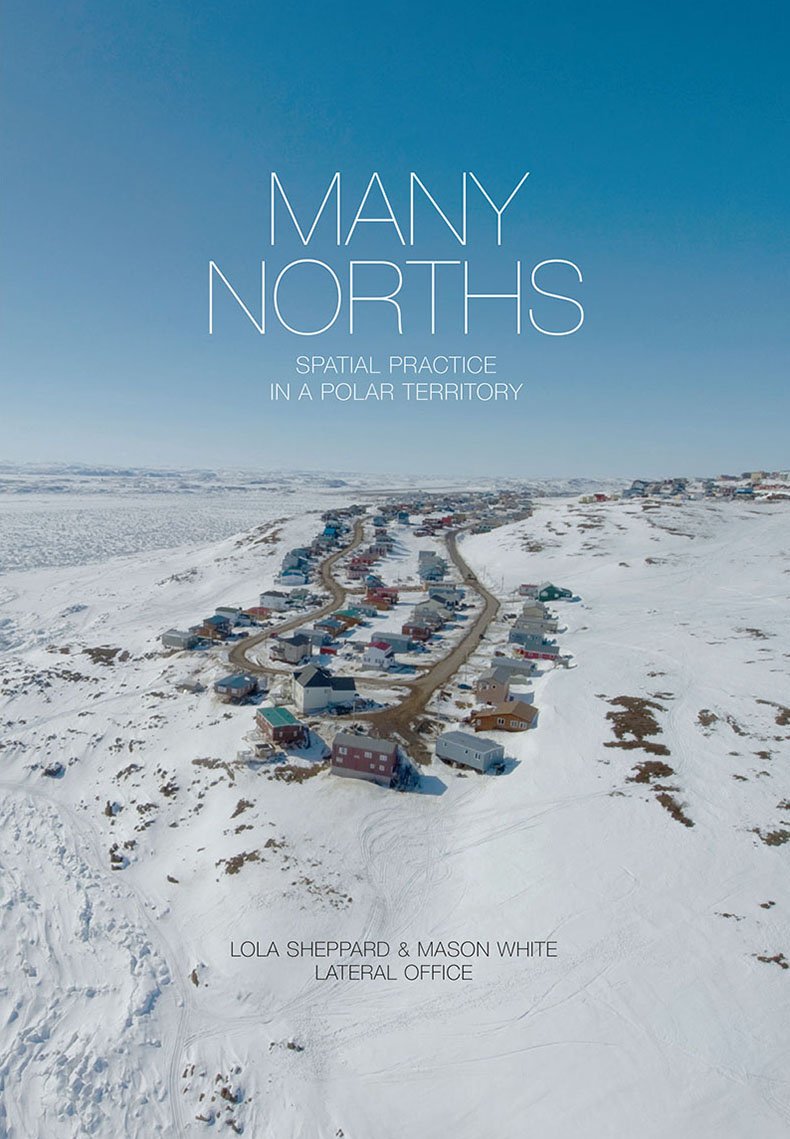

In his 1968 article “Architecture and Town Planning of the North,” architect Ralph Erskine writes “Do the cities and buildings of the North well serve the needs of the inhabitants? My answer: No.”1 It is a remarkable fact that you can count on one hand how many books—scholarly or otherwise—have been written about the design of buildings and cities in the Arctic. This is despite the fact that it is a region that spans eight nations, 5.5 million square miles, with about 4 million people and 40 different ethnic groups living in some of the most extreme cold climates on Earth. With almost daily headlines in the news that describe the impact of climate change and economic development, the design discourse about the region has continued to remain a veritable desert. With their new book Many Norths: Spatial Practice in a Polar Territory, architects Lola Sheppard and Mason White fill that void with 471 pages of dense, comprehensive, and inspired research. Not only does this work serve to recalibrate the ambitions and potentials of architecture and urban design in the Arctic, but Sheppard and White have also singlehandedly written what amounts to a manifesto and reference manual for Canadians and their northern half.

Following Lateral Office’s award-winning Canada Pavilion Arctic Adaptations at the 2014 Venice Biennale, Many Norths synthesizes Sheppard and White’s research on the Arctic from the past ten years. Referencing the work of Louis Hamelin’s seminal book Canadian Nordicity, It’s Your North Too (1979), and drawing inspiration from Glenn Gould’s documentary The Idea of North (1967) and the more recent film Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (2001), the authors define a set of criteria from which to establish the terms and operational modes for “spatial practice” within the Canadian North, with a goal to “chart both the essential historical trajectories and the new realities that have yielded a contemporary, urbanizing Arctic” (ix). The result is a sequence of five key chapters: Urbanism, Architecture, Mobility, Monitoring, and Resources. Each chapter has a consistent sequence and format, beginning with a historical timeline, a thematic overview essay (for example, “Urbanism Below Zero, Impermanence: Building at an Edge”), interviews with leading figures related to the chapter topic, and a series of carefully illustrated case studies. The book’s structure makes it easy to navigate and the parts can be read in sequence or independently, providing a multivalent way of engaging with the content. Importantly, Sheppard and White bring to the foreground the perspectives, histories, and traumas faced by the indigenous people of northern Canada, and seek to reframe the future of Canada’s North through the lens of an integrated and post-colonial narrative that identifies historical trajectories and future challenges in the Canadian Arctic.

Although there is an incredible body of knowledge that Sheppard and White have condensed into Many Norths, and a consistency and exquisite detail with their illustrations, I found the interviews—with their carefully formulated questions to experts from a wide range of disciplines and backgrounds in the Arctic—to be remarkable. On their own, these question-and-answer sections, which punctuate the book and complement the essays and case studies, are an invaluable stand-alone resource. Combined with frequent moments of synthesis and commentary such as “. . . architecture became a messy colonial exercise in rationalizing and retrofitting an imported model into a northern type. Among the isolated elements that required considerable modifications over this time may lie an embedded nascent vernacular, or evidence of an architecture that might have been” (130), Many Norths reveals itself to be the work of two authors with a depth of knowledge and experience that only a handful of architects share. I think the book could have benefitted, however, by expanding its scope beyond the singular Canadian Arctic context. The authors briefly acknowledge the differences particularly with Russia and northern Europe. But these regions have vast, technically sophisticated cities built on open tundra (for example, the former Soviet Union) and recent innovations in architecture (such as in Svalbard) that could help to contextualize the role of design in the Arctic region and the uniqueness of the Canadian Arctic context. Altogether, understanding the pan-Arctic successes and failures for the design of buildings and cities will lead to a wider range of ideas for future design strategies.

It is without doubt that Many Norths is a timely and critical contribution to design research on the Arctic and underscores how little currently exists. In total, there about four key books within which to situate Many Norths: Eb Rice’s Building in the North (1975), Boris Culjat’s doctoral thesis Climate and Building in the North (1976), Vladimir Matus’s Design for Northern Climates: Cold-Climate Planning and Environmental Design (1988), and Harold Strub’s Bare Poles: Building Design for High Latitudes (1996). Of these, Many Norths stands alone in its breadth and scope. By foregrounding spatial practice, Sheppard and White include a much broader perspective on design, ranging from building components to continental systems, from cultural identity to economic realities. Its lineage can be traced back to early seminal works whereby observation, data, and the synthesis and spatialization of large amounts of data and information from a wide range of disciplines became part of the means of architectural production. This mode of operating has roots in the work of Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi’s book Learning from Las Vegas (1972), which was essentially a treatise on “learning from everything.”2 Later examples took this idea to a logical conclusion whereby the volume and form of information and data were literally expressed via physical weight and density of information, such as the Harvard Graduate School of Design Project on the City books in collaboration with Rem Koolhaas/OMA (such as The Great Leap Forward [2002]), and Endless City (2008), where data literally spills out on the cover of the book and the emphasis on cultural, social, and political contexts becomes as important as the design of cities and buildings themselves. What Sheppard and White have done is dialed back the excess and condensed their research and synthesis into a well-tuned volume that is accessible outside of the design profession, which has grown accustomed to research books that are gravitationally challenged. For this reason, and the effortless negotiation between rigorous scholarship and practical illustrations and case studies, Many Norths is accessible to a broad audience that includes both specialist and nonspecialists; Sheppard and White have accomplished a daunting task that will no doubt have a long-lasting and far-reaching impact. As we seek to develop new ways of designing and adapting buildings and cities globally as a result of the impacts of climate change, the Arctic—and the research presented in Many Norths—will provide an important framework and reference. Coming from a region where people have lived and thrived for millennia in extreme and dynamic conditions, the lessons that are learned in the Arctic will undoubtedly have implications for designing smarter and more resilient cities globally.

How to Cite this Article: Jull, Matthew. Review of Many Norths: Spatial Practice in a Polar Territory, by Lola Sheppard and Mason White, eds. JAE Online. February 23, 2018. https://jaeonline.org/issue-article/many-norths-spatial-practice-polar-territory/.