Terreform, ed.

Urban Research, 2018

Reducing the smog-choked dome hovering over China or altering the course of rampant urbanization are daunting problems. The opacity of Chinese politics makes solving either one of them out of reach for most. We are left with the hope that one day soon the leaders of China will understand the science behind creating a sustainable future and act to make that future a reality. After all, the presumptive answer to how ideological transformations transpire in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is from the top down, but a close reading of Letters to the Leaders of China enables us to see something incomprehensible. The introduction, “Can China’s Cities Survive?”, written by the erudite and late Michael Sorkin, eloquently describes the fantastically rapid urbanization underway in China for the last two decades. The compendium, edited by Sorkin’s studio Terreform, goes beyond a celebration or critique of the projects of Kongjian Yu’s prolific multidisciplinary design practice Turenscape. It provides insight into the shrewdness of a passionate and ethically driven human being who understands that efforts to bring about a much-needed ideological shift in Chinese society today must be rooted in politics and persuasion. The dearth of literature on transformational leadership in the design fields serves to highlight that Yu has operated in this territory—to astounding effect—for the past quarter century. Lest we ascribe magical powers to him, the question of how on earth Yu has been able to make a dent in the Chinese government’s shield of opacity begs to be answered.

The book is organized as a tetralogy. The reader needs to work diligently to mine each part for the source of Yu’s determination. A young boy of four at the commencement of the Cultural Revolution in 1967, he gained intimate knowledge of sustainable agricultural practices firsthand. What Yu later recalled as a simple and humbling life was shattered when China opened relations with the West. The widespread application of DDT destroyed the very habitat of his boyhood. In a 2019 interview he shared with me a vivid memory of the bloated white bellies of floating fish turned to the sky—a moment when, I believe, he linked the actions of big government with life on the ground. The end of the Cultural Revolution meant that Yu was able to receive an education, a path that ultimately led to Harvard where he earned his Doctor of Design in 1995. These nuggets of information help us understand how this remarkable man established his passion for the environment and human rights and how he earned his academic credibility. Both led to the development of an authentic voice and to his ascension to a platform from which to speak and be heard by those who can effect deep systemic change in Communist China.

Kongjian Yu is a model of ethically motivated transformational leadership in the 21st century. Sorkin, too, identifies Yu as a leader, but falls into the irresistible trap of many male commentators on leadership: he uses military terms such as “generalship,” “army,” and “battlefield” to describe Yu’s modus operandi. A more refined vocabulary and understanding of leadership is urgently needed today. Part I, “The Writings of Kongjian Yu,” demonstrates that Yu has a full grasp of this new leadership and, therefore, has much to teach us all. He has humility, heart, a message of urgency, a compelling narrative, a clear understanding of the institutions that control the systems, credibility, and, above all, enduring patience.

The “Writings,” composed between 2003 and 2015, comprise letters addressed to mayors, ministers, party secretaries, and even one to Xi Jinping, president of the PRC, interspersed with lectures from that same period. In this collection, it is possible to extract patterns of Yu’s effectiveness. As Sorkin notes, Yu wants to tap China’s capacity to think and act at scale. Yu understands that mayors responsible for city-building, and experts serving mayors, are motivated by the idea that success involves the embodied emulation of Western cities. Mayors are his audience, and he appeals to shared language and experience, making a plea for the reverence of nature and of people. He names the movements he is seeking to begin “Negative Planning” and “The Big Foot Revolution.” He rejects the old thinking of the West’s City Beautiful Movement, which he regards as pretentious and emotionally vacuous. Yu’s counterproposition is a rallying cry; a century earlier, the May Fourth Movement, a symbol of the New Cultural Movement, had brought about a renaissance establishing a vernacular language. He laments that the designed landscape of China is untouched by the new Cultural Movement; only then does he list the practices that must be stopped. Yu’s visions of the future embody the humane and pragmatic; appreciate ordinary people and ordinary things, and respect and adapt to natural processes.

More heavily weighted toward establishing context than criticism, Part II, “Criticism and Context,” is biased toward the architectural facade of urbanism. Discourse about landscape in China is strikingly absent. The context provides a history of China’s urban patterns, and an explanation for the failure of the Eco-City Movement. One essay celebrates Yu’s accomplishments, comparing his work in scale and scope to that of John Lossing’s 1937 three-volume work, Land Utilization in China. The collection of essays in Part II, which were not published in China, could have been augmented by contextual essays describing China’s environmental degradation along with a critique and interpretation of the big systems thinking and Yu’s appeal for a National Ecologic Security Strategy. It is highly likely that Yu was one of the major players in influencing this national narrative. It has now been explored in Beautiful China (2020), edited by Richard J. Weller and Tatum L. Hands, an examination of Xi Jinping’s recently launched national policy for a “Beautiful China,” which is predicated on building an ecological civilization.

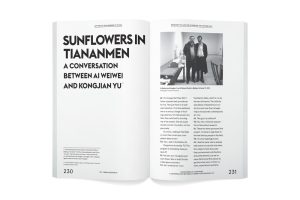

Part III, “Interview,” is a transcription of an important, raw conversation between Yu and Ai Weiwei, a globally acclaimed artist with a deep social conscience. The conversation, titled “Sunflowers in Tiananmen,” has a jocular tone. Yu and Ai imagine fantastical transformations of China’s most acclaimed structures: changing the CCTV Headquarters in Beijing into a vertical pig farm or the Bird’s Nest (Beijing National Stadium) into a farmer’s market. Yet we glean that Yu and Ai share a precarious place, wrestling with how to bring about change in a communist regime. Yu, a member of the Communist Party, clearly has opted to work from within the system, taking few risks, although his criticism of Chinese gardens was enough to temporarily excise him from the Chinese Society of Landscape Architects. But his visions also are ambitious. Yu works to mobilize the party machine. His quiet approach to effecting change requires extraordinary restraint and patience, a wisely chosen path in a culture prone to censorship.

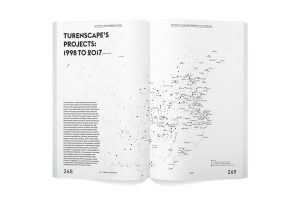

It is unfortunate that the book ends with Part IV, “Maps.” The maps locate nearly 2000 projects in 200 cities where Yu’s huge studio Turenscape has imprinted its philosophy in the minds of mayors and in the earth of the cities. They cover a quarter century of important and breathtaking transformations. Yet this ending leaves us wondering if Yu’s empire has created room for the next cohort of landscape architecture movers and shakers. Yu might consider writing letters to them.

Lucinda Sanders is a design partner and the president and CEO of OLIN. She has a core belief that transforming thinking transforms place, and she is eager to bring this idea to the design table wherever she works. Sanders is responsible for continually shaping OLIN as a leader in design excellence. She has led the design of many of OLIN’s signature projects and is the co-founder of OLIN LABS, the studio’s in-house research practice. Outside of OLIN, she is involved on boards and with academia dedicated to the advancement of the fields of landscape architecture, urban design, and planning. She co-created and co-facilitates the Landscape Architecture Foundation’s Fellowship for Innovation and Leadership.

How to Cite This: Sanders, Lucinda Reed. Review of Letters to the Leaders of China: Kongjian Yu and the Future of the Chinese City, by Terreform, ed., JAE Online, June 4, 2021.

All images in this review courtesy of Urban Research.