May 26, 2013-April 6, 2014

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

Turrell is often associated with the so-called West Coast Light and Space artists, such as Robert Irwin and Doug Wheeler, who pioneered alternative art practices in the 1960s that were inspired by Los Angeles’s surplus of sunshine and open space. In contrast to East Coast minimalists of the period, such as Robert Morris and Fred Sandback, who were preoccupied with framing space, the Light and Space artists reveled in the dissolution of space. In their works, matter gives way to dematerialization. Holes and cutouts replace chain link and yarn, and low resolution stands in for high definition to reconsider what the definition of “is” is.

Of the forty-nine pieces exhibited in the sixteen rooms of Turrell’s retrospective, four types represent turning points in the artist’s career, and each type can be categorized by humble or highly orchestrated means of working. Turrell’s crude drawings of Mendota Stoppages (1969-74), which describe outdoor light piercing darkened interiors, are first. The similarly homespun Projection Pieces that form illusory figures from artificial light follow. These relatively simple pieces are juxtaposed with a range of elaborately constructed works, such as Shallow Spaces and Space Division Constructions, which are otherworldly, immersive environments derived from the complex engineering of synthetic light. The exhibition culminates in a spectrum of elaborate space-bending works that includes Light Reignfall (2011), part of the Perceptual Cell series, and Ganzfeld (2013), which was specifically designed for the exhibition, as well as an expansive room dedicated to the Roden Crater Project, Turrell’s lifework.

The journey begins with a concise summary of Turrell’s artistic beginnings shortly after graduating from Pomona College in Claremont, California. He worked in the vacant Mendota Hotel in Ocean Park, California, from 1966 until 1974, when the landlord evicted him (Figure 1). Architectural-looking drawings record the Mendota Stoppages works. But rather than depict plans for constructing space, the artist’s charcoal and gouache vignettes demonstrate how tangible materials are subtracted and replaced by light. One set of elevation and plan diagrams indicates small holes scratched through windows painted black to allow tiny beams of external light to penetrate the hotel’s interior. Turrell’s life-size camera obscura illustrates light’s unique material qualities. The Wite-Out in the drawings on display serves as a vestige to the scrappy spirit and low-tech immediacy of these early works.

Of the Projection Pieces that follow, Afrum (White) is perhaps the most symbolic. In this 1966 piece, also produced at the Mendota Hotel and first presented at LACMA’s Art and Technology exhibition in 1971, Turrell’s premise that light makes space rather than simply illuminating it comes to life. Again, using uncomplicated and relatively inexpensive projection methods, a beam of light forms a radiant cube just above the floor in the corner of a darkened room. The walls dissipate and Afrum appears to float in midair. But with one step to the left or the right, or one blink too many, the light retreats and the walls resurface.

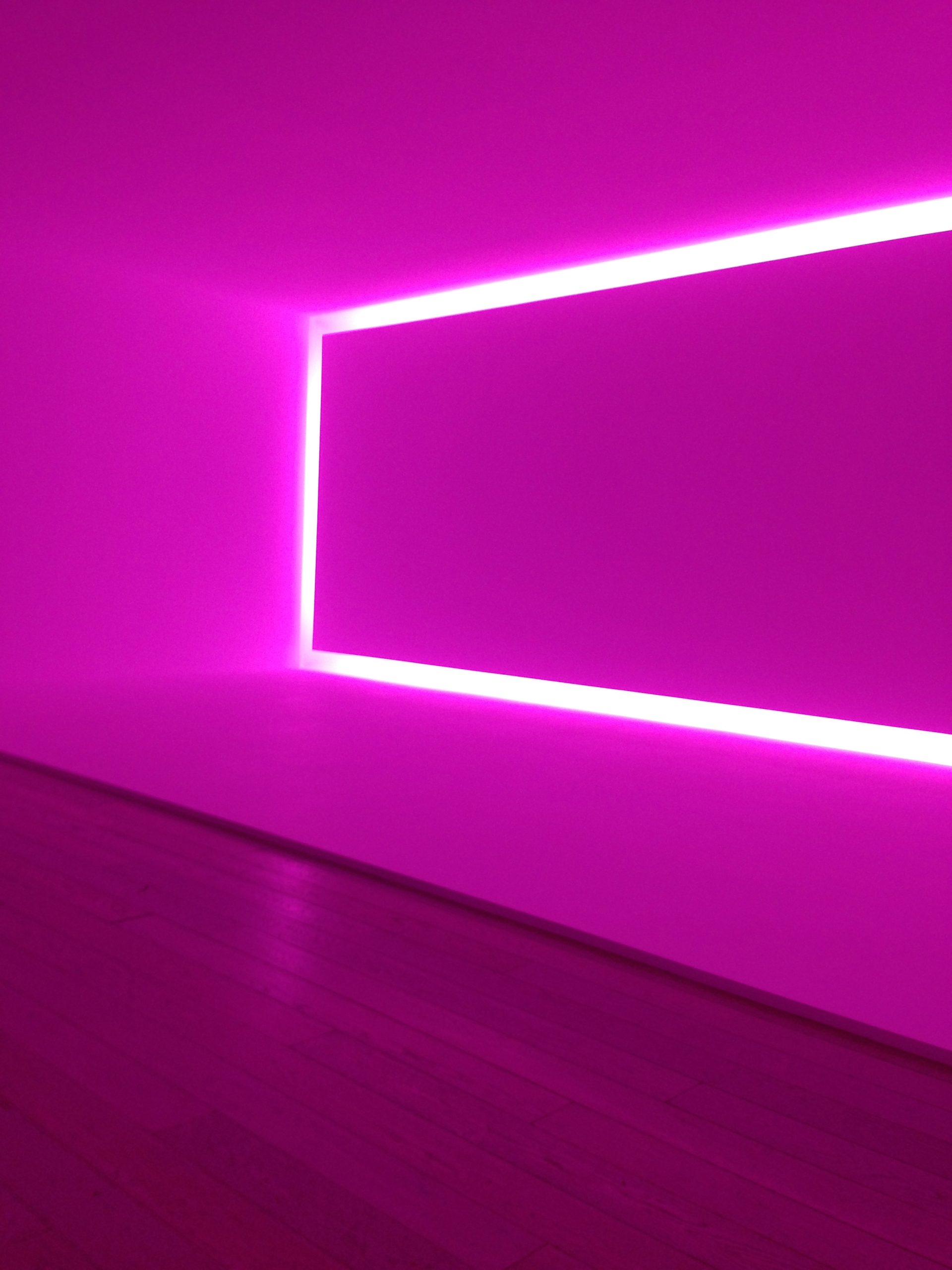

Raemar Pink White (1969) is part of the immersive Shallow Spaces series. An immense 50-by-10-foot LED screen lodged in a narrow cavity in the room’s far wall illuminates the space (Figure 2). A rectangle carved from the wall produces a flat and two-dimensional light source. From the rear of the space, radiant particles emit a soft atmospheric cloud, washing away all recognizable boundaries and rendering an unfamiliar and strangely ethereal pool of pink. Nearby is the tripartite St. Elmo’s Breath (1992), which is part of Turrell’s later iterative series Space Division Constructions. At first, the blackened floor looks as though the next step is into the abyss. Once the eyes adjust to the room’s dimness, three quivering figures come into view. A rectangle flanked by two squares of identical proportion and colors are made from incandescent and fluorescent light of varying intensities. Although impossible to touch, they beckon us to try. Soon one discovers that the shapes are not projected onto the walls but are lit portals from spaces beyond. Like Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus, whose body traverses a mirror, if viewers were allowed to plunge their arms through the portals of St. Elmo’s Breath, it might provoke an overwhelming desire to say farewell to the corporal world.

Curiously, the exhibition occupies the entire second floor of Italian architect Renzo Piano’s Broad Contemporary Art Museum (BCAM) and a portion of his Lynda and Stewart Resnick Exhibition Pavilion, in galleries usually illuminated naturally by saw-toothed roofs. This reenactment of Turrell’s process of blocking out natural light by covering every aperture encourages exhibition-goers to contemplate the tenuous veil separating the outside world from the interiorized context of the museum.

Three-quarters of the way through the exhibition, one returns to the day-lit room in the BCAM where the exhibition began. Suddenly the view and light, which went virtually unnoticed before, are omnipresent. A mélange of limpid sky, the Resnick Pavilion’s glistening rooftop, and exotic flora foreground the impromptu urbanism mangled with power poles and palm trees beyond. The panoramic image recalls Mike Davis’s inquiry into Los Angeles as the place between “sunshine and noir” and metaphorically reinforces Turrell’s own poetic outcomes from scrappy origins. Without the view to the outside, it is easy to forget the gritty context from which most of Turrell’s work initially emerged. Neither the wasteland of Ocean Park’s Main Street nor the desolate Arizona desert were popular destination points before Mendota Stoppages and Roden Crater Projectwere conceived. Turrell’s progression corresponds to the practices of many other West Coast artists and architects of his generation. Better known for his titanium-clad Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao and the reportedly $240 million Walt Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles, Frank Gehry’s early work relished in using cheap materials and was often described as “thrown together.” Philip Johnson once dubbed another Los Angeles architect, Eric Moss, “the jeweler of junk.” Twenty-five years later, Moss’s panoply of adaptive reuse projects has spawned gentrification and out-of-control redevelopment in Culver City’s postindustrial district, Hayden Tract.

No other part of Turrell’s retrospective makes the distinction between scrappy origins and posh outcomes clearer than the last few installations in the Resnick Pavilion. There, the collaborative installation with Robert Irwin, Breathing Light (2013), sits alongside the Perceptual Cell, entitled Light Reignfall (2011). An immense model, along with photographs, maps, and drawings dedicated to the Roden Crater Project replicate the multimillion-dollar installation that Turrell is building in an extinct volcano in the Arizona desert (Figure 3).

The spectacularly sanitized conditions in which this and other works are exhibited at LACMA—foot booties, attendants in white lab coats, and constant prodding from museum guards not to touch or wander—make it impossible to appreciate the spirit and place in which most of Turrell’s early work and the ongoing Roden Crater Project are born (Figure 4). No longer of the street and great outdoors, most of Turrell’s works now reside on the rambling estates of private collectors or under the grasp of institutions. Even the Roden Crater Project, in the remote high desert, is virtually impossible to access without the “right” credentials. While the LACMA retrospective reconnects many of Turrell’s works to a broader audience, it nonetheless left this viewer lamenting what has been lost along the way.