Katie Lloyd Thomas, Tilo Amhoff, Nick Beech

Routledge, 2015

Of the many images that accompany the 32 essays compiled in Industries of Architecture, a blurry and ill-composed photograph, taken on a construction site, best illustrates the field of inquiry that this book unlocks. The photo shows a piece of plywood; in the lower right corner is a hastily drawn sketch in marker by an unnamed worker (Fig. 28.1, 308). Any architect engaged in construction administration has seen such evidence of real-time problem-solving by workers on site—a calculation on a 2-by-4, a detail sketch on raw gypsum board—that becomes embedded within the body of work itself and erased from view. The unprepossessing photograph of one laborer’s contribution to a single building project begs a larger question: could we write a history of architecture that takes these hidden scraps of the construction process as its source material? (Certainly there are now scanning techniques that make this type of inquiry possible.) Might such a project finally lay bare the constant negotiation required by laborers on site to bridge the gaps between design concept and materialization? The fact that I have never given a second thought to these on-site scribbles, and yet now can imagine a new genre of architectural history, is testament to the intellectual potential embedded in Industries of Architecture.

Industries of Architecture is an edited volume that emerges from an Architectural Humanities Research Association (AHRA) conference of the same name, held in Newcastle, United Kingdom, in 2014. The conference gathered an unusually wide-ranging collection of scholars, design practitioners, governmental representatives, filmmakers, and other construction-engaged professionals to foreground the too often sidelined “industrial, technical, and socio-economic contexts in which building is constituted.”1 The conference organizers, also the editors of the book, argue that “industry is never just a matter of technology, but always also a matter of social organization and social relations” (2). Because the editors assume such a capacious definition of industry, they are forced to corral the heterogeneous short essays in the collection into eight very broad categories like “the construction site,” “economy,” “law and regulation,” and “technologies and techniques.” Individual texts within these categories range from essays on architecture’s engagement with standardization in the early and mid-twentieth century, to topics rarely touched in humanities scholarship, like the spatial effects of finance capital, the day-to-day impact of building codes on architectural practice, and most importantly, on- and off-site labor conditions.

The wide scope of practice-based inquiries included in Industries of Architecture marks the ascendance of an orientation toward economy, governance, and labor in architectural scholarship advocated by Italian neo-Marxist architectural historian Manfredo Tafuri some forty years ago. Tafuri urged his scholarly peers to focus on “the dialectic . . . between concrete labor and abstract labor,” by “putting primary emphasis . . . on the function of the work itself within the relations of production.”2 If Tafuri is the invisible guiding hand, the specter haunting this endeavor is Marx himself. Many of the contributing authors to Industries of Architecture demonstrate abiding interest in architecture’s labor, both concrete and abstract, and more than a few call for architects to disrupt the smooth advance of late capitalism. Yale professor Peggy Deamer speaks directly to this imperative in her essay when she writes, “if we architects cannot identify as workers, we fail to politically position ourselves to combat capitalism’s neoliberal turn” (146).3 Sérgio Ferro, a Brazilian émigré architect in political exile in France since 1971—a revelation in these pages—pushes the labor agenda even further to include equal concern for construction workers.

The introduction to his book Dessin/Chantier (Design/Construction Site, originally published in Portuguese in 1979), translated for inclusion in Industries of Architecture, argues that the goal of design must be to reunite labor dispersed by capital, and that the locus of politically agitational collective work, undertaken by laborer-architect and laborer-builder, will be the construction site itself (98).4 One cannot help but recall Zaha Hadid’s response to questions about migrant worker deaths on construction sites in Qatar, where her World Cup stadium project was the prominent focus of a government architectural program, to understand how far we have come, as a profession, from viewing ourselves in a sympathetic, never mind comradely, relationship with the men and women who construct the buildings that we design.5

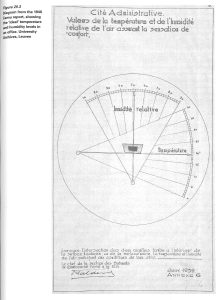

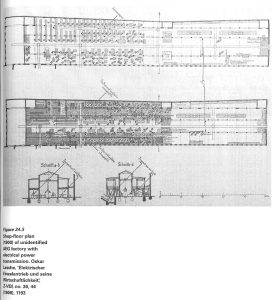

A number of authors in Industries of Architecture speak to this fact by introducing a complex cast of characters (engineers, construction workers, clients, lawyers, planners, financiers, politicians, among others) whose impact on a given building project is elucidated only through the inclusion of technical literature as source material. Texts and diagrams of AEG factories by German electrical engineer Oskar Lasche, for example, demonstrate convincingly that the flexible open floor plan we associate with modern industry was largely a function of the transition from mechanical to electrical power (Fig. 24.3, 263). Or consider the impact on early twentieth-century governmental architecture in Brussels by high-ranking civil servant Louis Camu, whose obsession with scientific management resulted in reports filled with cryptic charts and graphs that architects had to decipher and grapple with in their designs (Fig. 25.3, 275). Make no mistake: scholarship that takes account of the collaborative nature of building is more complex to research and resists neat narratives. But it is faithful to the stubbornly nonlinear, dialogic process of building.

Industries of Architecture is a book that dares to mix genres. Many of the essays written by scholars are heavy on theory and would be relatively opaque to a lay reader, while some of those contributed by practitioners (especially in the final section on contemporary questions) are straightforward, if dry, reports of ongoing programs in practice. In other words, Industries of Architecture is a bit uneven—a quality in keeping, nevertheless, with its aspirations to inclusivity.6 This is an edited volume that has utility for numerous audiences: from practitioners to historians to enlightened clients. The great benefit of the book is that, once they have cracked the binding, Industries of Architecture invites these typically siloed actors to consider the ways in which their work is mutually constituted.

How to Cite this Article: Crawford, Christina E. Review of Industries of Architecture, by Katie Lloyd Thomas, Tilo Amhoff, and Nick Beech. JAE Online. November 16, 2017. http://www.jaeonline.org/articles/reviews-books/industries-architecture#/.