Sun-Young Park

University of Pittsburgh Press

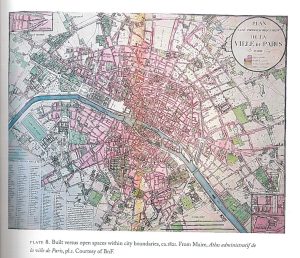

Sun-Young Park’s important new book, Ideals of the Body: Architecture, Urbanism, and Hygiene in Postrevolutionary Paris, reassesses our understanding of Paris—indeed, of modern urban reform itself—as pre- and post- Haussmann, the old city and the new, by excavating a complex history of military, civic, educational, medical, and commercial approaches to reshaping Paris. Park accomplishes this by tethering the built environment to evolving concepts of health and the body between 1800 and 1850 (Figure 3). She argues, fundamentally, that many of the anxieties involving class, gender, sex, and social status that have driven (and continue to drive) modern obsessions with the body, particularly its health, aesthetics, and fitness, were already ubiquitous in early nineteenth-century Paris (Figure 4). By bringing to light the architectural plans for hundreds of projects, Park makes a strong case for the idealism of the human body as an undergirding philosophy for the construction of the built environment and implies historical connections to later middle-class urban reform movements (Figure 5). Park consequently pushes back the periodization of urban modernity, and its relationship to modern concepts of health and the body, to an era before fully developed industrial capitalism. She writes that “In the era when the bourgeoisie was first emerging to control the city, and before the networked urbanism associated with their dominance assumed recognizable form, a seemingly disparate range of everyday environments generated experiences perceived, then and now, as modern—in their cultivation of active principles, their democratic agenda of progressive and attainable improvement, and their culture of spectacle” (6–7). The theoretical implications of this argument are significant—prior to the social scientific imperatives of professionalized medicine and the commodification of the body by advanced consumer capitalism, the control, mobility, aesthetics, fitness, and hygiene of the corporeal self were already embedded in the conceptual health of the nation and its foremost structural representation, the capital city (Figure 6).

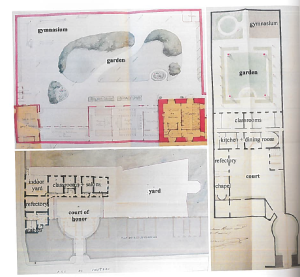

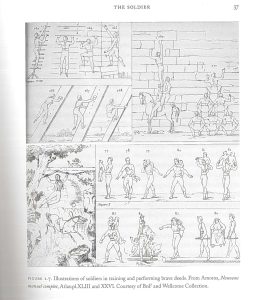

Park embarks on this archivally based narrative by organizing the book around the themes of physiologies and the threshold. First, physiologies refer to literary tropes of bourgeois urban types (e.g., the flaneur) that were popular in early nineteenth-century French writing and “recounted the typical traits, habits, and settings of each social character, demonstrating the belief that environment could shape one’s appearance and disposition” (17). These physiologies include the soldier, schoolboy, schoolgirl (demoiselle), lionne (a variant on the “new woman”), and sportsman (Figure 7). Second, the threshold is a spatial metaphor to suggest impediments to, and the porousness of, social and physical mobility. If nothing else, the marriage of the built environment to the health of the body was about exerting control over masses of people while offering a sense of liberation through artificially created recreational and “natural” spaces. The dialectical relationship between control and liberation produced physical, social, and cultural tensions that placed limits on how much pressure could be placed on the body—either its mobility or its containment. As Park puts it, “the environments studied in this book, though having defined architectural limits, were social thresholds in their totality—‘varied, multiform, and hybrid’ spaces of experimentation, at the juncture of the private and public spheres, where emerging class identities, gendered constructs, and experiences of modernity were forged” (13).

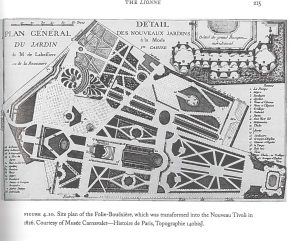

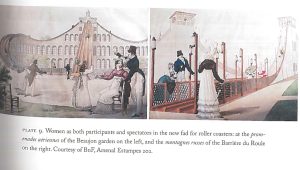

Park is at her best when describing the embodied experiences of philosophies about the relationship between health and the built environment. Chapter 4, “The Lionne: Pursuing Health and Pleasure in Leisure Gardens,” is a marvelous case in point. Here, Park demonstrates how private gardens evolved into places of public leisure that, rather than becoming sites for simple physical play, emerged as complex environments for the display of the constructed female bourgeois self. Bicycle races, walking promenades, balloon rides, and roller coasters (decades before the amusement parks, penny arcades, and cheap amusements of the urban industrial era) created exciting, sexualized spaces for middle-class women while providing carefully prescribed edicts for appropriate behavior (Figures 8–10). Even more compelling than the gendered construction of these spaces for health and fitness is how truly modern they seem, with machines placed in the garden as evidence of the “nature” of things.

The book is beautifully executed, but one oversight is worth mentioning. A few of the architectural plans Park excavates were unrealized; thus, the question arises, Why were they unrealized? The answer(s) may be lost to history, but the public’s response to the monitoring and control of their bodies might not have always been positive, leaving the spaces for physical and healthful experience unused or perhaps even abused. Could a negative public reaction have placed limits on the architecture of health? Archival sources on this point are likely limited, but further investigation into how public subjects for the built environment of health and hygiene received these designs for their wellbeing may have deepened the book’s already extensive historical analysis.

Sarah Schrank is Professor of History at California State University, Long Beach. Her research and teaching specialties include the modern United States city, the politics of the body, and the relationship of the built environment to art and cultural expression. She is the author of many articles and essays as well as the monographs Free and Natural: Nudity and the American Cult of the Body (2019) and Art and the City: Civic Imagination and Cultural Authority in Los Angeles (2009). She is also co-editor of Healing Spaces, Modern Architecture, and the Body (2017).

How to Cite this Article: Schrank, Sarah. Review of Ideals of the Body: Architecture, Urbanism, and Hygiene in Postrevolutionary Paris, by Sun-Young Park. JAE Online. September 27, 2019. http://www.jaeonline.org/articles/review/ideals-body.