Review By: ALEXANDRA OETZEL

February 14, 2025

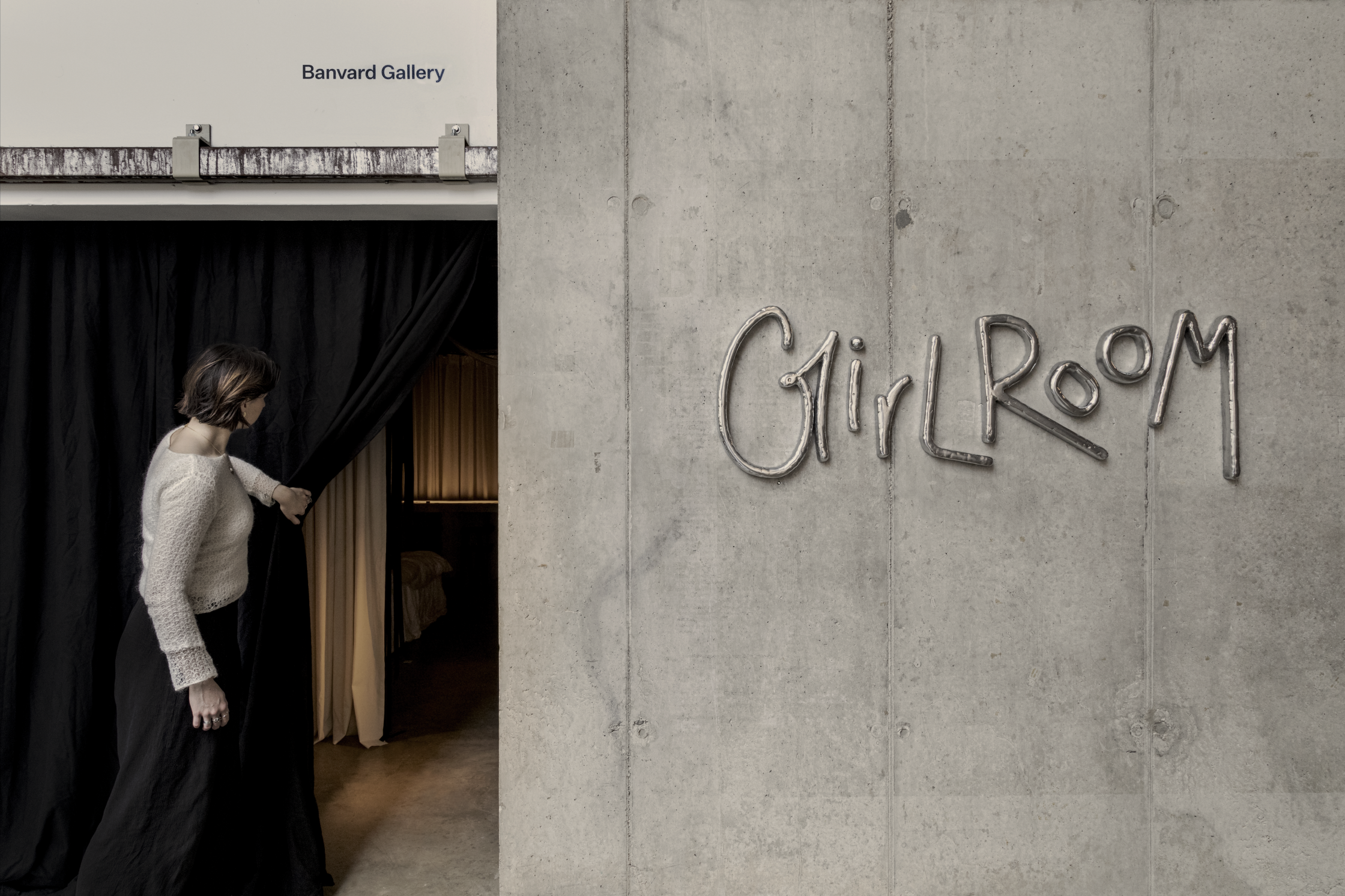

I like to think I’m intimately familiar with the space under the stairs—the strange concrete gallery of Ohio State’s Knowlton Hall, with its sloped ceiling, too-hot spotlighting, and dusty corners. Yet Girlroom, an installation by designer and theorist Samiha Meem, offered a compelling transformation of space, identity, and intimacy in an otherwise austere gallery. Girlroom was an all-encompassing living environment, equally soft and horrible in a way that the gallery architecture itself, conceived by Mack Scogin Merrill Elam Architects, can never be.

Figure 1: All images courtesy of Knowlton School

As the 2023–23 LeFevre Fellow at the Knowlton School, Meem opened her fellowship lecture by referencing Britney Spears, the era-defining pop princess whose conservatorship has raised concerns and conspiracies in recent years. Spears’ social media appearances and disappearances over the course of her conservatorship were confusing and bizarre, leaving audiences to speculate multiple realities: clues, cues, and hidden meanings could be uncovered in every TikTok. Was she held against her will, bound by the frames of the phone, or finding autonomy and reach in the media? The mediation of this pop icon is a perfect analog for Meem’s growing body of research, which foregrounds an auto-space where personal is obviously political. It is with this attitude that the viewer is meant to enter the Girlroom.

Figure 2

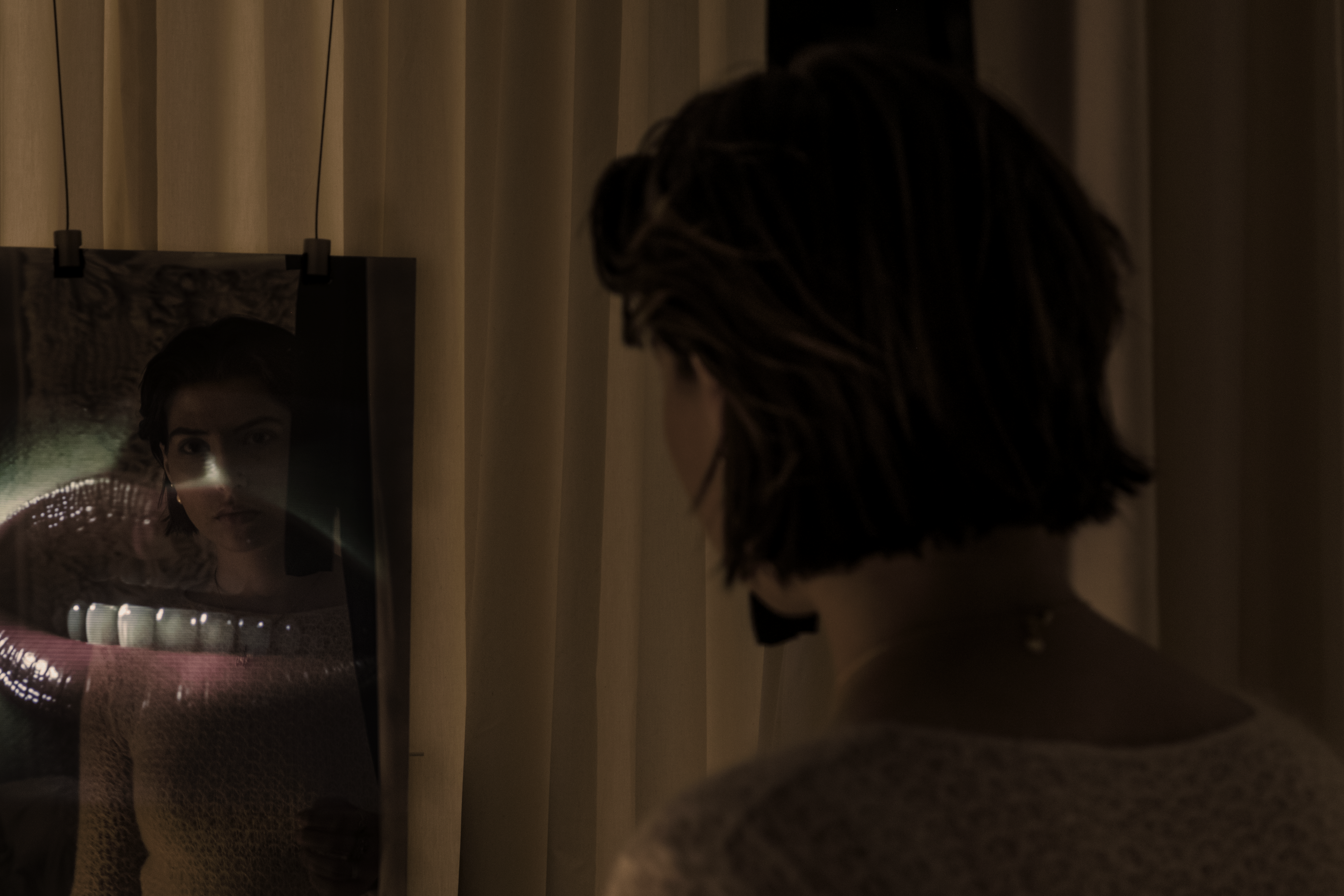

I visited the room several times during the exhibition, seeking both restoration and rot in its beguiling bed. Black and white curtains, hung from exposed steel members above, defined the perimeter of the room and its interior contents. Walking through the space counterclockwise, the viewer encountered a bed first, inviting them into a space of intimacy. Canopied overhead by another curtain and stuffed with pillows, the bed was accompanied by a projector on a side table, which casted distorted stills and sounds from Meem’s collection of archived Tumblr blogs above. The third main exhibition component was a series of large drawings, distended across three mediums: rich textile constructions, transparent printed sheets, and the occupied space between. Smaller clusters of things (photos, bows, mirrors, data) were built up around the corners and piled atop flat surfaces, inspiring theft and tampering from guests. Meem’s triptych of composite surfaces—wall, screen, drawing—tied together the immaterial and material, constructing a narrative about consumption, disfigurement, and occupation across multiple realities.

Figure 3

The totalizing environmental transformation achieved by Meem’s wrapping of visitors in muslin curtains is particularly meaningful in the context of Knowlton’s otherwise cold concrete structure. Pulled off the existing concrete walls by four feet or more, the curtains created a newly compressed, dense room in the range of 400 square feet—a womb, of sorts. Known for its ability to appear both sheer and coarse, gauzy and smooth, the fabric added a tactile dimension to the space but also introduced a history of gendered boundaries. The simultaneity of muslin textile—which summons tradition, craft, and even nature—and contemporary digital culture does not set up a familiar dichotomy between the genders. Rather, Meem’s enchantment with the girl and computer subverts gender constructs and labor expectations by collapsing the closed dichotomy between man and woman, suggesting a broader, stranger vision of material, identity, and space.

Figure 4

Simone de Beauvoir describes this familiar dichotomy between man and woman in The Second Sex (1949). The woman is an “other,” capable of less than her counterpart and, in general, quite horrifying to behold. Her body mutates, bleeds, and decays. Her beauty is fleeting, but boy oh boy, is she useful! Diana Agrest reframed this dynamic relative to architectural design, where an architect (i.e., a man) desires to fulfill the procreative act and raise good, beautiful buildings. The whole of women is suppressed so that men can realize these fantastical reproductive acts. However, without the physical disfigurement of their bodies, men can never fully embody the feminine. If Girlroom is intended as an addendum to the postmodern lineage of feminism, we might also consider the work of Mirele Laderman Ukeles, who understood that under the male gaze she could not be both serious artist and useful mother. Feeling frustrated and constricted by housework, she defined a manifesto that outlined these interdependent systems of labor: development (creation) and maintenance (care). The girl’s room then becomes a curious site of architectural study, as it substitutes the normative gendering of reproduction and care with a different kind of relationship, between a girl and her computer. This relationship is rooted in shared, collective experiences, in the mutating and aggregating of feminine bodies. As a result, the girl and computer are fundamentally ambiguous, comprised as they are of various simultaneous and contradictory fictions (recall here our pop idol, Britney Spears). So then, too, must the Girlroom exhibition capture an atmosphere of loose, overlapping identities with collective authorship, constructed in unfamiliar and immaterial ways.

The exhibition’s most provocative element was the bed, centrally positioned in the installation as a space of performance and dialogue. The use of a bed in an art or architectural performance is not new—consider Beatriz Colomina’s Bed-In installation during the 2018 Venice Biennale, in which she interviews dozens of cultural figures in their pajamas. Yet the bed’s position in an academic institution draws another comparison, more ambiguous than the dichotomy between intimate and private, professional and public—that is, a dialogue between production and consumption. This was the center around which exhibition viewers yapped and desired over the course of the exhibition, simultaneously contributing and observing. The bed also became the stage for two slumber parties, featuring designers (Olivia Rose, Avery Norman, Rayne Fisher-Quann, and Adrienne Economos Miller) in loose conversation with students about gender, production, and image. Blurring the lines between private and public and elevating “meritless” girl talk, these slumber parties can be considered one of the most successful aspects of the exhibition. The place of the gallery was reinscribed for the purposes of collective experience as opposed to display and objectification.

Figure 5

The bed also provided surprising moments of quiet relief. On one occasion I lay in the bed, joined by fellow girl Sandhya Kochar, watching projected film disfigurements cycle above us. The speed of the day halted, and we breathed—for seconds, minutes, hours. The wails of women and creaking floorboards above, distorted and returned via artificial images and audio, centered our bodies in a shared experience of introspection. In this moment, we were reminded that feminine bodies are malformed and grotesque, transforming during puberty, menstruation, and childbirth into strange forms. Our eyes are closed as we extricate ourselves, piece by piece, from the carefully crafted performance of being a girl in public. The space was liberating, as opposed to controlling, as it allowed us to recreate, redefine, and remove our identities, confirming, albeit within the exhibition context, that collective design, between girl and computer, is good and necessary to unwork centuries of masculine focus.

And then, suddenly, students appeared! Pulling aside the curtains to enter, they brought light and chatter with them, and I felt a similar disruption as Otessa Moshfegh once shared; “I was both relieved and irritated when Reva showed up, the way you’d feel if someone interrupted you in the middle of suicide.” I was irritated to join a present that so quickly objectified and managed my body, but relieved, of course, to return from the brink of the unknowable. The manufacturing of this type of experience in Girlroom elevates an architecture of entanglement and empathy, miring us in experiences that are not wholly our own.

Figure 6

Meem’s collapsing of embodied and digital “girl” experiences recalls key works since the 1990s which assess technoculture’s transformation of gender. These include Sadie Plant’s Zeroes and Ones (1997), a text that argues that women’s intersection with information technologies would allow them to be liberated from the institutions and frameworks that control them. A shared transformation into complex, thinking machines would end our objectification, consumption, and exchange. Relatedly, N. K. Jemison’s short story “Too Many Yesterdays, Not Enough Tomorrows” (2004), portrays a postapocalyptic near future where isolated individuals are each day wiped of their intimate histories and identities outside of public blogs. Jemison’s characters must deliberately distance themselves from deep connection to remain alive and present—if they get too close, reconnect with a lover or mother, they vanish. In addition to making possible neologisms such as #freeBrittany, these works, like Meem’s exhibition, ask us to evaluate the computer as a mode of liberation and the computer as end. Can the self—or the girl’s self—exist without a computer? If girl and computer are the same, bound together in a “composition of links,” Girlroom suggests that we may have already been folded into some alternate reality.

Alexandra Oetzel, AIA, is an adjunct faculty member at the Knowlton School, Ohio State University and practicing architect at Moody Nolan. Her design research explores the relationships between form and finance, foregrounding the no-good, underhand, and overlooked. Her professional experience focuses on higher education spaces of learning and recreation.