April 3, 2015-April 4, 2015

Parsons New School of Design

Attending last month’s conference at Parsons School of Constructed Environments on the subject of “Feminism and Architecture” was an interesting interlude from a busy practice and teaching schedule that rarely permits this “female architect” to think about the status and progress women have made (or not) in the field. For this alone, I am grateful to the organizers for reaching out to so many women and bringing together an impressive series of panels and presentations to compare notes and share strategies for advancement. The presentation format was quick and interesting, consisting of short, pecha kucha–style slide shows to maximize participation, followed by real discussion and workshops, not merely the standard Q&A that often follows.

As the day unfolded with presentation after presentation considering the metrics of gender and how to increase the representation of women in academia, one image kept returning: an inversion of the title of Duchamp’s intricate and fractured construction, the isolated figure above and the gyrating herd below, spectating, longing, and competing to cross from the bottom glass pane to the top. Instead of a female figure floating above, however, the image that sprang to mind was that of the male architect, that Mad Man in silly glasses and tasteful suits, cowering in his corner office, clinging to what’s left of the creative endeavor that we call “architecture” like a polar bear clinging to the last piece of ice in the Arctic Ocean. Beneath him, his bachelorettes sallied round and round, one a sustainability consultant, another an installation artist, a third interior architect, another public relations and business development professional, pushing forth and peeling off one skill at a time, leaving precious little to the figure above. In the end, I felt only pity for the groom.

As a conference on women in architectural education, the image felt even more poignant. Gertrude Stein once wrote, “It takes a lot of time to be a genius, you have to sit around so much doing nothing, really doing nothing,” (Gertrude Stein, Everybody’s Autobiography (1937), chap. 2.) and this, sadly, is where the core of architectural practice is headed. To be as blunt as possible, women have been barred from the privilege of “doing nothing” in this field and been forced to march off with all the hard parts in a bloodletting exodus that has brain-drained the profession of most of its profitable services and left only inconsequential creativities in its place (fancy teapot anyone?). Corporate architectural practice is filled with women, as are faculties in architectural education: they are project managers, LEED-certified lighting designers, history teachers, proposal and firm bio writers, interior designers, parking specialists, commercial kitchen consultants, environmental systems teachers, design communication teachers, installation artists, photographers. So who is designing the buildings? Well, guess what, folks: men still design buildings. Who is teaching in the design studio? Men.

It is for sure an extremely sticky wicket. The future of the profession depends on whether it can call its prodigal daughters home, because if they are left out in the cold, stuck in the bottom pane of glass, these bachelorettes will take the field with them. In fact, they already have. Come to think of it, the women are doing fine. It’s the men I worry about.

The brightest ray of hope at this conference came, completely not surprisingly, from the youngest women presenters, students in architecture actively shaping a new feminist discourse, citing the #LikeAGirl ad that premiered during Super Bowl XLIX (and if you know what that number is, you are a man) this year. As a jarring reminder of how backward our field remains, our feminist discourse seems to be lagging just behind this new campaign for maxi pads by Procter & Gamble’s Always brand. By now, with effusive praise for the campaign subsiding, we are reminded (by Amanda Hess at Slate) that “it’s a little sad that all of this enthusiasm for women’s stories are leading us directly to a box of maximum protection with wings, while female filmmakers and characters are still so underrepresented at the box office.” And female architects are still so underrepresented in the corner office.

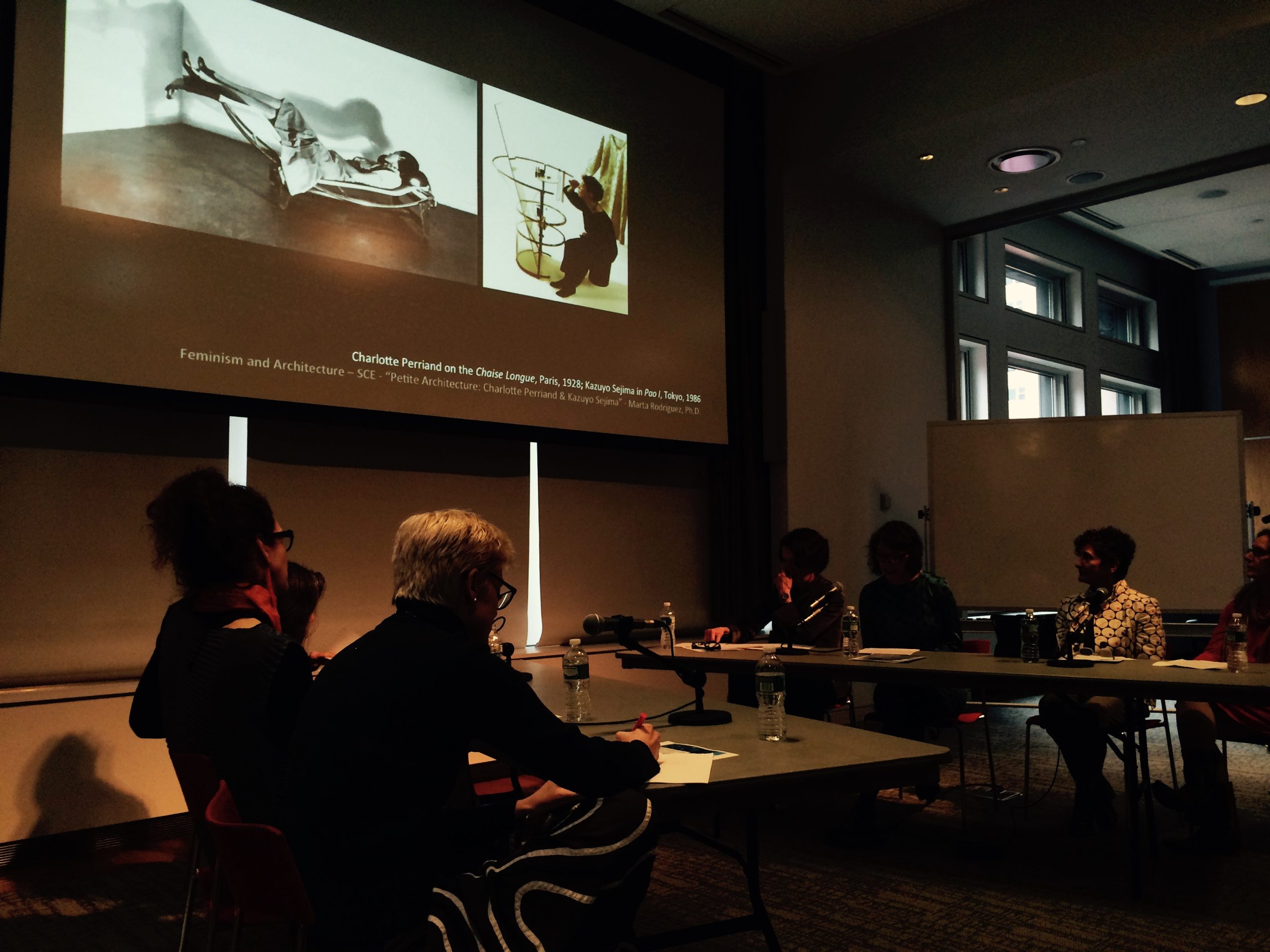

Looking a little more closely at the conference, there was the usual grab bag of feminist tropes, from the pitiable percentage of women guest speakers at schools of architecture last fall (according to a presentation by Lori Brown of Syracuse University), to Carla Corroto, PhD, and Lucinda Kaukas Havenhand, PhD, quoting Audre Lorde’s 1984 essay “The Master’s Tools,” which noted all the white feminists whose homes and children are being tended by women of color so that they might attend this conference, to the importance of Charlotte Perriand’s “petite architecture” as relayed by Marta Rodriguez, PhD. And herein lay the weakness of the conference: a sad old return to appropriating and aggrandizing the smaller bits and edges of architecture, where the battle for creative leadership is more easily won.

Now watch me as I immolate myself before you by stating this: furniture is not architecture. Environmental graphics are not architecture. Skirts, tents, and pottery arrangements are not architecture. I state this not as an attempt to belittle the work of the “petites architectes”; rather, I will simply say this: don’t give up yet. Women must acknowledge their own significant and substantial power in society, if not in the field itself. In cleverly carving out creative practices from the impenetrable edifice that is building design, women have literally carved up architectural practice in its conventional, “heroic endeavor” sense and left it in shreds. And the bottom line—the proof of this particular pudding—is this: buildings have not become better; they have become worse. Architects do not earn more; they earn less. Architects—even the sincere, spend-my-free-time-reading-architecture-books architects—are less valued members of the professional services community—the professional with the lowest hourly rates on the A-E team. Correlation only?

In the last slide of her keynote, Katja Tollmar Grillner of the KTH in Stockholm, posted a list of positive actions that women bring to the field. This is a much more productive approach than attempting to redefine the field such that women can succeed more easily while raising families. Women must come to the field bearing gifts (in a blaze of codependent glory?). The time is right, and the men are ready to receive them: think of corporate America’s now standard “parental leave” policies instead of “maternity leave” policies. If, instead, we take the gifts of holistic thinking, detail-oriented analytics, social intelligence, and yes, multitasking, away with us to new practice formations or to other fields, we will succeed in one thing only: making bad buildings with good furniture.

How to Cite this Article: Richmond, Deborah. Review of Feminism and Architecture: Women, Architecture, and Academia, organized by Peggy Deamer. Parsons New School of Design, New York, NY, April 3-4, 2015. JAE Online. May 23, 2015. https://jaeonline.org/issue-article/feminism-and-architecture/.