NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE PRESS, 2023

Review By: Ying Sze Pek

NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE PRESS, 2023

Review By: Ying Sze Pek

July 19, 2024

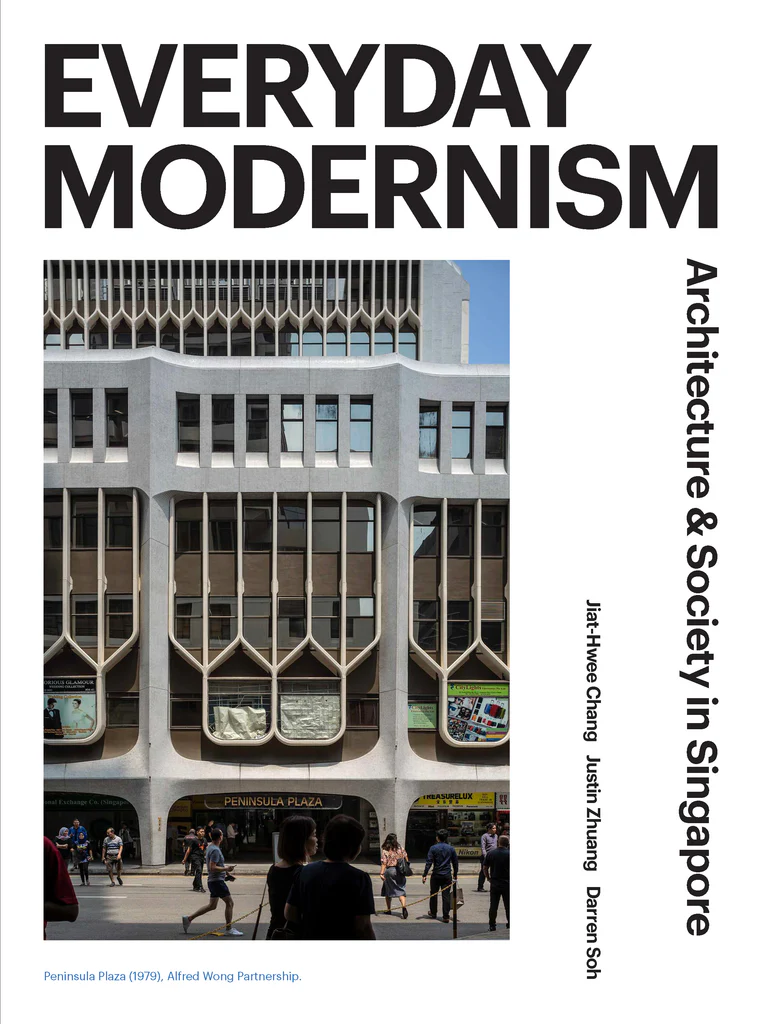

Following Singapore’s transition to self-governance in 1959 and eventual independence from British rule as a republic in 1965, growing housing needs and subsequent waves of industrialization saw the island-nation’s landscapes and coastlines radically transformed, and its population’s ways of living and working fundamentally reorganized. Everyday Modernism: Architecture and Society in Singapore makes a case for what Chang and Zhuang term the “Singapore vernacular” covering this period up to the nation’s economic prosperity in the 1990s. Putting together an insightful volume that catalogues buildings and structures representative of the time that they were constructed, the authors evoke a vernacular that refers not so much to a single style or building typology, but everyday rather than iconic architecture, at all scales, built for civic, industrial, educational, and entertainment purposes. The authors understand the everyday-ness of this architectural modernism as a concept that is “both specific and general,” which describes buildings of unknown authorship, such as those planned by architects working for government agencies, as opposed to the “heroic modernism” of contemporary projects designed by renowned local practitioners. Another facet of the everyday is the expanded sense of architecture that describes not only building projects but utilitarian structures—overhead bridges, multistorey carparks, hawker centers that house affordably priced food stalls—interwoven in the modern city’s infrastructure.

Comprising an introductory chapter and thirty-two short entries organized under the sections “live,” “play,” “work,” “travel,” “connect,” and “pray,” Everyday Modernism explores buildings and built structures that were determined both directly and incidentally by Singapore’s postwar fortunes as an ascendent Asian Tiger market economy, closely directed by a technocratic government. Through these categories or what the authors term “key verbs,” which appear to revise the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM)’s midcentury ideas of the city’s functions that also influenced Singapore’s 1950s urban planning, the reader navigates the country’s architectural modernity: the Jurong Hill Watch Tower marked the transformation of former swampland into a heavy industry manufacturing town from the 1960s; flatted factories of the 1960s and early 1970s gave way to brutalist-inspired buildings along Jurong Town Hall Road in the 1980s IT age; the space-age Futura private apartments (1975) or tropically landscaped luxury Shangri-La Hotel (1971–78) catered to well-heeled locals and foreign executives with the rise of the financial services industry in the same decade.

One of Chang and Zhuang’s objectives across their entries, which proves instructive, is to uncover loose genealogies of types: for instance, the tower podiums that integrate commercial and residential spaces, first developed by the Housing and Development Board (HDB)—successor to the colonial government’s housing agency Singapore Improvement Trust—in the 1970s, have found a footing in building projects up to the present. The integration of lush greenery in the earlier mentioned Shangri-La Hotel, a translation of Hawaiian resort architecture to Singapore’s equatorial tropics, can be regarded as a precedent for many post-2000s high-rise projects that incorporate vertical gardens. Chang and Zhuang also survey the extensively planned towns and private housing projects beyond the city center, proposing that the architecture of everyday modernism is such a functional part of the urban fabric that its users often take for granted its merit or innovation. The HDB built upon the typology of the low-cost rectilinear slab block from 1952, experimenting with layout combinations and façade designs to efficiently house a population that would grow accustomed to high-rise living. (Eighty per cent of the country now lives in government-built housing.)

Figure 1. Tan Cheng Siong of Archurban Architects Planners, Pearl Bank Apartments (1976–2019). Photograph by Darren Soh, courtesy NUS Press.

Yet the modernist architecture that Chang and Zhuang feature would in fact appear outdated to current Singapore residents. Although a number of these projects were spectacular additions when they were built, many are in a state of disrepair today, if not already demolished, and they are dwarfed by the constantly renewed, land-scarce city-state’s more recent starchitect projects. It comes as little surprise, as referenced in a footnote in the introduction, that Chang and Zhuang, as well as photographer Darren Soh, are founding members of the Singapore chapter of DOCOMOMO (Documentation and Conservation of the Modern Movement), established in 2021, and on whose executive committee Chang serves. DOCOMOMO Singapore’s website lists numerous buildings that are also featured in Everyday Modernism, with the indication that many of them are unlikely to be conserved.

Perhaps above all, then, the volume seeks to record these sites and structures as a part of Singapore’s architectural history, and the forms of documentation that the book undertakes can be seen as twofold: first, the essays constitute a conscientious compilation of the histories of buildings and urban spaces little-known beyond specialist circles. Accessibly written and brimming with historical detail informed by local scholarship and archives, especially newspaper sources, the short entries also reproduce rare photographic or documentary material: the entry on swimming pools features images of colonial-era facilities with extravagantly shaped diving platforms (150–51); advertising posters depicting expressways, condominiums, revolving restaurants, and hotels evoke the exultation in new construction (195; 106–07; 138–39; 133). Second, the publication collects documentary photographs by Soh, a noted Singaporean practitioner who works in photojournalistic and art contexts. Bookending the volume’s essays is a striking 100-something page spread of Soh’s images, printed in full color, in which apartment blocks, former school buildings, cinema complexes, and children’s play areas alike are portrayed with an aestheticized monumentality—starkly lit and frequently framed from a wide angle and an elevated perspective. His photograph of the sun-dappled, crumbling façade of the blue-bricked Queenstown Cinema and Bowling Center, to take an example, grants a certain grandeur to a forlorn structure that lay unused between 1999 and its demolition about a decade later.

Figure 2. Chee Soon Wah of Chee Soon Wah Chartered Architects, Queenstown Cinema and Bowling Centre (1977–2013). Photograph by Darren Soh, courtesy NUS Press.

An outcome of such striking strategies of depiction, where spaces and structures are often devoid of human figures, would in fact seem contradictory to what Chang and Zhuang evoke: through Soh’s lens, this modernist architecture is rarely shown in a state of inhabitation or use. Yet the photographic elevation of the quotidian and the obsolete seems calculated to the cause of cultural memory, rather than simply nostalgic. More than Chang and Zhuang’s texts, Soh’s images directly appeal to readers’ lived experiences of the city, giving shape to a collective memory opposed to developmentalist free-market logics. Everyday Modernism serves as a repository of information and documentation that will raise awareness about Singapore’s architectural modernism, supporting the government’s belated conservation measures and potentially reversing the trend of leveling even beloved national symbols.

As a kind of exploratory atlas of Singapore’s post-1959 built environment, Everyday Modernism’s patchworked format articulates a function- and user-centered approach to a postwar architecture that integrated modernism, modernization, and nationalism, as favored in some non-European countries. Chang and Zhuang’s focus on the category of experience proves unique among recent publications on architectural modernisms beyond the West, such as Urban Modernity in the Contemporary Gulf: Obsolescence and Opportunities (Roberto Fabbri and Sultan Sooud Al-Qassemi, eds., 2022) and The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947–1985 (Martino Stierli, Anoma Pieris, and Sean Anderson, eds., 2022). Beyond scholars of modern architecture and urbanism, the volume’s rich collation of historical material will appeal to researchers or general readers interested in the social history of Singapore. The latter group would nonetheless be inclined to bear down on Everyday Modernism’s subtitle, Architecture and Society in Singapore, and probe the scope of the “social”: which decision-makers and stakeholders are included or overlooked in this examination of the architecture’s features and functions? Chang and Zhuang’s broad characterization of Singaporeans’ affinity for the country’s “utterly modern” built environment by the 1980s can be challenged. Such totalizing modernity was double-edged. Although the authors acknowledge that the urban transformations were enacted “top-down” and reflected the “high modernist” ideology of the state, referencing political scientist James Scott with the latter term, their account leaves little room for the histories of resistance by individuals and communities toward such development. Absent in their volume are also an assessment of this architecture’s environmental implications and mention of the labor behind its construction, pressing questions that might be furthered by future research.

Ying Sze Pek is a scholar of global modern and contemporary art and a postdoctoral researcher at the German Research Foundation (DFG) research training group Documentary Practices: Excess and Privation at the Ruhr University Bochum, where she is developing a book project on the media histories of film pedagogy and moving image exhibition in postwar West Germany. She completed her PhD dissertation “Reality Expanded: The Work of Hito Steyerl, 1998–2015” at the Department of Art and Archaeology at Princeton University in 2022.