Daniel Winterbottom

Routledge, 2020

Design-Build: Integrating Craft, Service, and Research through Applied Academic and Practice Models addresses design-build in landscape architectural education. It is an inspiring and practical start-up book for educators who want to include more aspects of design-build in their classes and provides a scholarly grounding for this practice. Its author Daniel Winterbottom is a licensed landscape architect and professor of landscape architecture at the University of Washington where he founded the design-build program in 1995.

Design-build is an integrated way of designing and building, one that does not separate “design” done by one group from the “build” done by a second group. In landscape architecture and architecture pedagogy, the design-build model offers ways “to be of service to”: ways to work in and with a community, and to collaboratively design and build places or objects that are useful to those who live there. There is a design-build focused book from 2018—The Design-Build Studio: Crafting Meaningful Work in Architectural Education (ed. Tolya Stonorov)—that is a useful resource focusing on the construction of small buildings. There are many other design-build books that address the professional practice of design-build. But to my knowledge, this is the first on education through design-build in landscape architecture.

Figure 1. Construction of a garden for the Japanese Cultural Community Center of Washington, Seattle, Washington. UW Landscape Architecture Design/Build Program May 2014. https://designbuild2014.wordpress.com/2014/05/04/basket-shelter/.

As the book discusses, and as many of us have observed firsthand, attitudes to design-build have really changed. Design-build hasn’t always been seen as way of creating and delivering a rigorous design studio or of being a creative design practice. There has often been a perception that design-build means that building, not designing, is the focus. Design students today are increasingly passionate about alternative and emerging practices, and many of these, if not most, include design-build in their work—although it is often called fabrication, implementation, or prototyping. Empowering students who do not have any previous connection to construction is something that even a more traditional studio can offer. Winterbottom’s book has some useful examples of this, such as developing skills in using tools. I can attest to this in my teaching. Students, overwhelmingly female students so far, have told me about the exhilaration they feel as they learn to operate the table saw, for example, and make their own first cuts.

One of the strengths of Design-Build is that it addresses issues like this head-on. The book is part manifesto, reminding us of the power of the sensory, the physical, and the tactile; part history, recounting a lesson of design-build studio classes emerging as activism in the 1960s; and part theory, discussing methodologies and precedents for teaching and practice. The final chapter focuses on case studies from different design-build landscape architecture studio programs. Full color photographs are effectively used throughout, showing work both under construction and completed.

Figure 2. A sensory garden designed for the Puget Sound VA serves veterans’ family members while their loved one is receiving treatment. The garden functions as a living room where families members can meet others in a similar situation and offer respite and support surrounded by herbs and aromatic plantings. Photo credit: Daniel Winterbottom. Design-Build p. 266.

The book’s final chapter, “Case Studies,” is especially helpful; Winterbottom and five other academic leaders take us “behind the curtain,” showing how they set up and run design-build studio courses. They offer frank discussions of what worked well, what didn’t work as well, and why. Their projects range from healing gardens to community gathering spaces and innovative infrastructure. Some are permanent; others are prototypes or temporary. The educators discuss the challenges to teaching this type of course, including acquiring funding for construction, the organization of students and community members, liability and regulations, the compressed timeline of a quarter or semester to complete a design-build project, and the heavy workload for the instructors as they manage the project while teaching construction skills. Each teacher has a different pedagogical model, and these descriptions are helpful to learn of and compare approaches if you are considering teaching a design-build studio.

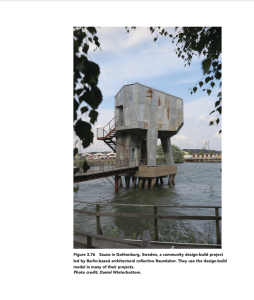

Figure 3. Sauna in Gothenburg, Sweden, a community design-build project led by Berlin-based architectural collective Raumlabor. They use the design-build model in many of their projects. Photo credit: Daniel Winterbottom. Design-Build p. 195.

The instructors also reflect on the joy these studios bring to students, communities, and teachers as they see the development of both hard and soft skills during the semester. The rewards of teaching from a design-build approach are plentiful, since skills and concepts that are usually taught in separate classes—studio, materials, technology, and community engagement—come together in one. Addressing the unexpected is always a component of design-build and students learn to strategize, improvise, and how to meet the delivery deadline. Design-Build reveals that these studios are a labor of love for the faculty members—taking much more time and expertise than a traditional studio.

A very effective part of the case studies chapter is the inclusion of interviews with the six design-build instructors. Yet the book would also have benefitted from more critical commentary on who does not teach design-build, what gets left out, and whose voices are missing. Winterbottom observes that design-build studios are frequently the most highly evaluated by the students for the impact they have, and he does include some student reflections in the book. As reflected by the contributors in this book, most people who teach design-build are men—who have often grown up with construction in their family or helped their fathers build. There is only one woman educator featured in the book—Julie Stevens, associate professor at Iowa State University—a fact that shines a light on gender disparities in design-build education. Her choice of subjects to explore in her studio is also telling. Her students collaborate with incarcerated women and prison staff to design and build garden rooms, including a recent garden for mothers and children. An afterword or summary following the “Case Studies” chapter would have been a useful addition to tie lessons together from the various voices—both present and missing.

Overall, this book is an excellent new resource for landscape architecture studios, materials and making courses, and professional practice courses. Design students want to engage real world issues while in school, and yet there are only a handful of programs in landscape architecture that offer design-build studio courses. There are more in architecture programs due to larger faculties and student bodies, but design-build is still not a common studio offering. Students are looking for meaningful ways of engaging with the world, and with an expanded range of teachings that are more analog, more outdoors, and more in service to community. The design-build model in pedagogy offers an effective approach to making a difference both in the physical world and within the participants themselves. Design-Build is an inspiration and guide to this old-new way of teaching and practice.

Figure 4. A sauna, kitchen and patio created over eight weeks through a design-build collaboration between the University of Washington, HDK-Steneby/Stenebyskolan, Dals Långeds Utvecklingsråd and Bengtsfors kommun in Dals Långed, Sweden. Photo credit: Daniel Winterbottom. Design-Build p. 79.

Rebecca Krinke is professor of landscape architecture at the University of Minnesota. She has designed and built exterior and interior installations with her graduate students as part of her hybrid practice and teaching. Krinke’s current writing project is a coauthored book on the art of Char Davies.

How to Cite This: Krinke, Rebecca. Review of Design-Build: Integrating Craft, Service, and Research through Applied Academic and Practice Models, by Daniel Winterbottom, JAE Online, August 27, 2021.