Pierluigi Serraino

The Monacelli Press

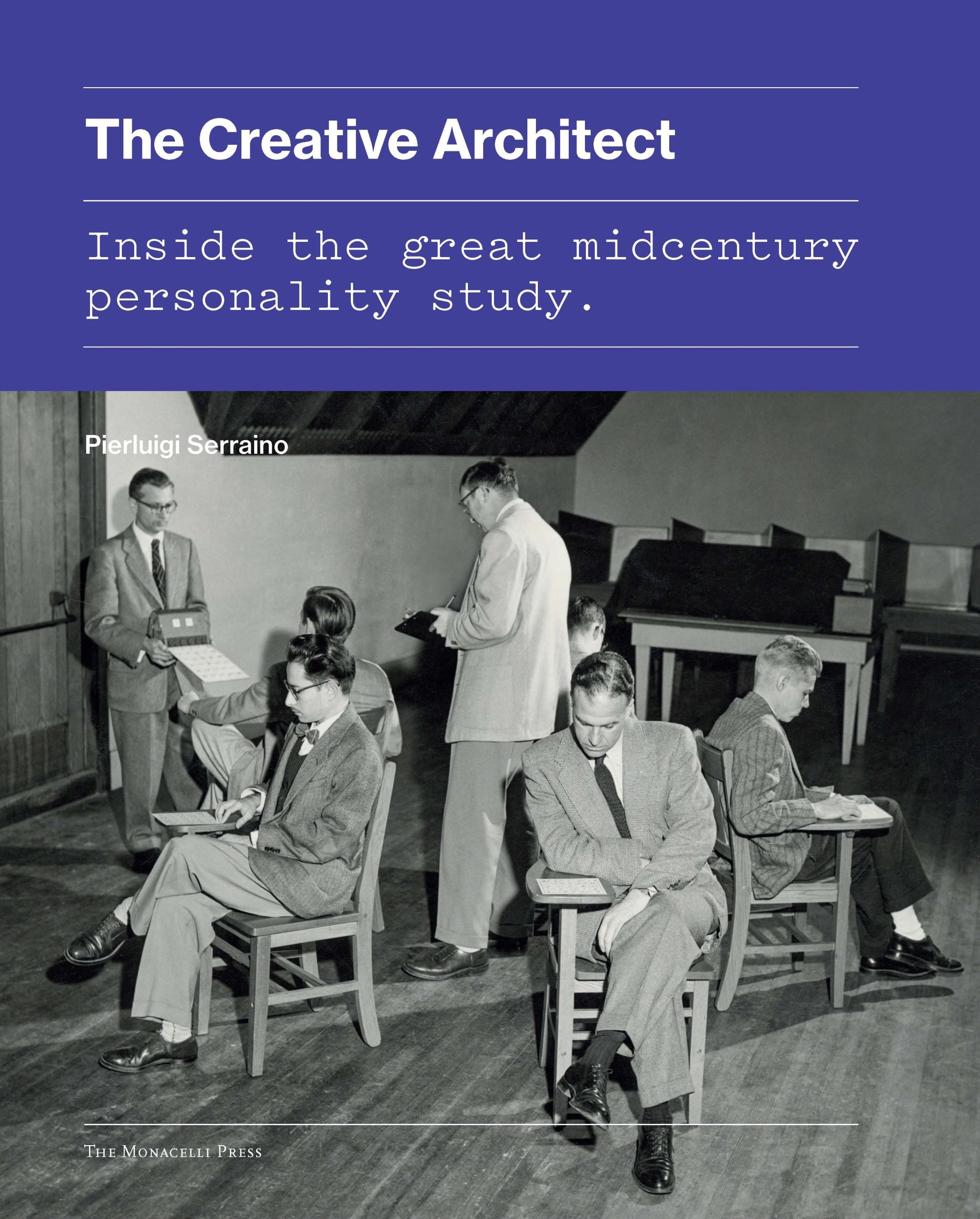

What makes a person creative? In the late 1950s, a group of psychologists at the Institute of Personality Assessment and Research (IPAR) at the University of California, Berkeley set out to answer this question in the most scientific way possible. The subjects of their long and wide-ranging study of creativity ranged from novelists to female mathematicians, but a group of sixty-four architects considered especially creative—Philip Johnson, George Nelson, Richard Neutra, and Eero Saarinen, among others—was its showpiece. The sheer density of design celebrity made the IPAR study the focus of a prolonged media extravaganza, but in subsequent years it quietly slipped into obscurity and was nearly forgotten.

Architect Pierluigi Serraino’s The Creative Architect: Inside the Great Midcentury Personality Study brings renewed interest to the IPAR project, turning the research study into a research subject. This engrossing monograph emphasizes the postwar socio-political matrix that incubated the urgent call to identify, and thence nurture, early signs of creativity. In exhaustive detail, Serraino situates the study within this broader context, including the principal investigators of the study, led by psychologist Donald MacKinnon; the myriad factors underlying the choice to study architects; the long process of nominating luminaries in the field to undergo testing; the painstaking ranking and dogged recruitment of study subjects; the complex logistics and setting of the intensive group testing weekends in Berkeley; and the nature and purpose of the individual tests administered to them.

This minute history is the stage upon which Serraino presents the IPAR creativity study as a flawed, yet still highly important scientific achievement. With its black and white photographs of IPAR staff in 1950s dress simulating various study conditions, this handsomely designed, high production value book effectively conjures the atmosphere of positivism that imbued the ambitious mission to scientifically identify the personality features that signaled special creative power.

The privileged glimpse into the workings of the minds of some of the most important architects of the twentieth century generates intense curiosity, and, in turn, an uneasy sense of voyeurism. We witness how architects rank their fellow colleagues’ talents and struggle with test puzzles—data that Serraino admits was “never intended to be shared with the public” (77). We learn who cheated (Oskar Stonorov); who outsmarted at least one study test (Victor Lundy); who was irreverent (Raphael Soriano’s word association to “religion” was “ignorance” [201], and George Nelson’s more direct response was “bunk” [182]); and who refused to take part (Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Louis Kahn, in particular). Given that IPAR chose not to release data on I. M. Pei or Victor Lundy because they were still alive during Serraino’s research, we are given to understand that the study’s “strict discretion” (143) around confidentiality issues expires along with its study subjects. (Serraino does not engage with this ethical gray area.) Yet, while cringing at the lack of diversity among the subjects—all are white men—we do gather new insights into some of them. For example, two of the stories Philip Johnson wrote for Thematic Apperception Test (TAT)—explanatory narratives elicited by ambiguous visual scenarios—feature automobiles running over a man or a woman (174). These imagined vignettes become more disturbing in view of their real life parallels: in letters written during his European tour in the 1920s, Johnson describes two separate incidents in which he plowed into a female pedestrian and a male cyclist, respectively, furious that they failed to yield to his touring car.1 It is entirely possible that his creativity allowed Johnson to sublimate his near-homicidal aggression into architectural domination, a more agreeable solution than manslaughter—or Fascism.

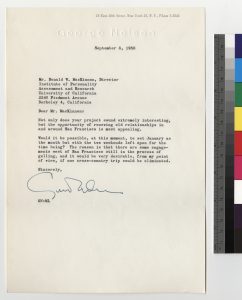

Figure 1. Letter to Donald MacKinnon from George Nelson, agreeing to participate in the study, Creative Architect 4.

In contrast to the many pages of The Creative Architect devoted to reverential, full color reproductions of archaic-looking data—typed lists, rankings, scorecards, and other tests results—relatively scant space is given to the results of their analysis. And, in a curious echo of the long delay between the data collection and the reporting of its analysis (Serraino suggests that it was this that caused interest in the study to wane), this analysis is also withheld from the reader—at first mysteriously, then irritatingly—until the very end of the book, and even then we only see a smattering. For example, we do not learn what, if anything, was gained by the extensively discussed tabulation of how the architects ranked each other in terms of creativity, given so much attention in the text. Although Serraino throughout the book lauds the IPAR study’s robust scientific objectivity, the few “quantitative” graphs and bar diagrams he presents lack error brackets or other markers of statistical significance, rendering them all but meaningless. Tellingly, although its publication was repeatedly announced, the book in which MacKinnon planned to present the outcome of the IPAR study (Creativity: The Psychological Study of Architects) was ultimately shelved, its manuscript relegated to the IPAR archive (104) and its “results” disseminated in various short articles. This is perhaps unsurprising: for all the tremendous buildup in The Creative Architect—starting from its introduction, which promises that “the very nature of creativity” will be “framed by the data that was actually gathered” (14)—this reviewer, a former basic scientist, comes away with the impression that in the end, the analysis of all this data failed to yield any substantive conclusions.

Why, then, did this historic study fail? There are two main reasons, neither of which The Creative Architect addresses. The first is the implicit presupposition that creativity is a discrete, homogenous quality that can be dissected and characterized; within this conjecture, what makes one person creative is the same thing that makes another creative. Especially given that a baseline degree of creativity is the rule, not the exception, what enhances it is complexly variable; the IPAR study is a test case for the failure of studies of aggregate samples to explain phenomena as polymorphous and complexly manifest as creativity. And while it may not be impossible to better discern what factors in different individuals may contribute to their own particular abilities—a sensitivity to form and pattern, a predilection for constructing novel solutions to problems, a pleasure in seeing ideas materialized—the study as designed was not powerful enough, and its tests likely not specific enough, to detect such nuances.

The second flaw in the study design is that its research sample was grossly pre-selected, reflecting the misguided assumption that greater success necessarily reflects greater creativity: the study compared “Group I” subjects, composed of sixty-four well-known, well-respected, and, most importantly, highly successful architects, to Control Group II, forty-three architects who had spent at least two years working with architects in Group I.

Figure 2. Ranking of participating architects by Architectural Forum editor in chief Peter Blake (left); 59b: Blake’s note on the verso of his ranking sheet (right); Creative Architect 59 and 59b.

For example, Group II included Landis Gore, who worked with Johnson, and who Serraino admits was “in a league arguably closer to Group I” (86). (The less problematic Control Group III was made up of architects chosen at random from the 1955 National Directory of Architects.) Serraino understands that the study’s choice to group for comparison the best known architects was a problem, conceding, “to a large extent,” this “list of sixty-four figures was a direct reflection of what was being published in books and magazines” as opposed to “the creativity of the architects themselves” (79). As a consequence, he notes, certain architects of “serious historical consequence” (55) that lacked corresponding media attention were excluded from Group I. Serraino does not appreciate the overriding and most serious implication, however, namely, that even if creativity were a homogenous, discrete entity, sampling bias in the composition of Group I and II—the more, and the less commercially successful architects—would make it impossible to parse those attributes that comprise or facilitate creativity from those prerequisite for commercial success. (A related but distinct difficulty with the research design is that it couldn’t discriminate between measurable character attributes that are secondary to success, rather than contributing to it).

None of this deters The Creative Architect from dramatically reifying the conclusions that MacKinnon extracted from the IPAR study: heading the final chapter (“Creativity Unveiled”), Serraino writes in bold type, “What propels creativity is the unfettered expression of the self. Donald MacKinnon realized this incrementally as he parsed through the voluminous data gathered under his leadership” (213); moreover, this data yields the “crystal-clear insight” that the creative person is one who will “consistently safeguard their self-determination… in a fierce escape from conformism of thought and behavior” (212). One would have expected more to follow from such an auspicious unveiling: albeit a refreshing correction to trends that downplay or dismiss the psychological underpinnings of architectural design, the notion that creativity is a means of nonconformist self-expression is hardly a new insight (nor, I might add, does the IPAR study prove the idea that self-expression is the engine that drives creativity). Indeed, this notion had already been forwarded by the very psychoanalytic studies that quantitative psychology aimed to supplant: Serraino himself credits the IPAR study for confirming previous work by Abraham Maslow, Ernest Jones, and others, who argued that creativity is actually quite common, even ubiquitous, but requires both a relative lack of inhibitory forces and a strong drive for self-expression in order to be realized. But the IPAR study didn’t separate these factors from others that facilitated the commercial and popular success of Group I subjects—be they an abundance of drive, ambition, initiative, confidence, interpersonal skills, financial resources, business acumen, managerial abilities, charisma, salesmanship, political talent, and sheer competitiveness, among other things. It is not clear whether Philip Johnson would have attained the same measure of success had he not been able to independently underwrite the expensive construction of the Glass House, the first structure to bring him to national attention. Nor could IPAR separate factors supposedly associated with decreased creativity from an excess of inhibitory factors such as fear (of failure, rejection, humiliation, envy, etc.), distractibility, pessimism, and tendency to self-sabotage—all of which could otherwise prevent a highly creative person from productively setting up their own shop.

Serraino sees it differently, however, breathlessly stating that IPAR “discovered that creativity is at its core an existential and unstoppable drive in those individuals who, free from repression, can act on their intuition” (213). To say that IPAR “discovered” anything about creativity is not only an overreach: it neglects centuries of philosophical, psychological, and psychoanalytic interrogation of just these ideas. Moreover, the conjecture that anyone could become “free from repression” is facile; inhibition is the correct term here, and no sane person is (or should) be completely free of it. But more to the point, Serraino’s pronouncement just pushes the problem of creativity a step back—into the no less murky, no better understood realm of talent, imagination, or “intuition.”

Figure 3. Evaluation of Philip Johnson by William Wilson Wurster, Creative Architect 48.

To his credit, the author makes earnest attempts to present an objective view of the study’s flaws, yet he routinely fails to grasp the extent of their ramifications for the project’s validity. While one wouldn’t expect an architect or architectural historian to have the level of scientific or psychological sophistication of an experienced researcher, it wouldn’t have been difficult to enlist one to help critique the study design. Lacking a sufficiently rigorous assessment, the text reads (to a scientist, at least) as a hagiography, its author as seduced by the study’s quantitative aspects as the IPAR researchers were by the fame of their study subjects. As a result, The Creative Architect accepts, unquestioningly, all sorts of antiquated and otherwise problematic methodologies and the data obtained therefrom. For example, the IPAR study utilized the Meyers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), a tenaciously popular assessment tool based on a reductive and outmoded model of personality. Widely criticized by the scientific community, the MBTI relies on false dichotomies expressed as a series of binary choices; for example, an individual has to be categorized as either “intuitive” or “perceptive,” but not both—even if they are both. (They also can’t be labeled as neither!) Thus, if the MBTI labels hypothetical study subject A as “perceptive” rather than “intuitive” because A is felt to be more perceptive than intuitive, while for similar reasons subject B is labeled “intuitive,” this does not guarantee that “intuitive” B is in fact more “intuitive” than “perceptive” A, or that “perceptive” A is more perceptive than “intuitive” B. The MBTI cannot compare individual categories between individuals, making aggregate conclusions meaningless

The Creative Architect does have its value. Much as the histories of individuals shed unique light on the more general aspects of times past, the astonishing breadth and diversity of man’s creativity is better appreciated by comparing multiple individual case studies. Accordingly, some of the book’s most successful pages are those that open windows onto the life stories of the representative architects; to this reader, what stands out is not how similar they are, but how different.

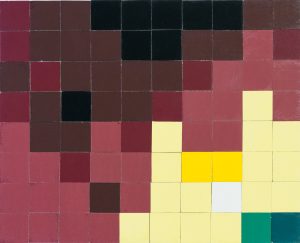

Accordingly, readers will also find some of the raw testing data of great interest. Take, for example, the architects’ responses to the Mosaic Construction Test—strikingly, one of the very few assessments of the creativity study that involves design or any visual aspect at all—in which study subjects are asked to make a design from colored tiles; all of Group I’s designs are beautifully reproduced in the book.

Figure 4. Philip Johnson’s mosaics test, Creative Architect 119.

When pressed, MacKinnon privately admitted to study subject Raphael Soriano that “to make any generalizations” from the mosaic exercise “would be hazardous indeed”; thus, he did not “place too much confidence in the results, since judgments of these sorts are highly fallible” (121).

This is not to say that the mosaic designs, some of which now part to the “mythology of post-war architecture” (120), offer no insights into individual subjects. Illustrating his vacillation between emulating and defying his masters’ idioms, Johnson, in response to the question “Were you attempting to construct something particular which you had in mind, some pattern or design, or did you improvise as you went along?” replied simply, “A Mondrian.” Johnson’s mosaic includes white, black, and red tiles—in his own words, a “primary Mondrian palette” (118; the author erroneously states that “Johnson only used black and white,” 120). I would have liked Serraino to discuss Johnson’s patently derivative design, a most provocative maneuver for someone so insecure about his own level of innovative creativity—the very thing under evaluation.

Figure 5. Richard Neutra’s mosaics test, Creative Architect 125.

Ironically, the modern myth of the avant-garde that conflates creativity with innovation1, and the architectural zeitgeist of the time that that endorsed this myth, informed the IPAR study’s fatal premise that the most successful architects must be the most creative. The quest to divine the source of innovation capped the end of a singular and heady architectural decade, in which the dominant Miesian idioms and Bauhaus functionality of the International Style give way to a new architectural currency, one fathered by Frank Lloyd Wright, which venerated above else endless variety in design. With the relatively new opportunity for the kind of celebrity long enjoyed by writers and painters, architects jockeyed to inherit Lloyd Wright’s legacy of architectural genius (bolstered by his constant innovation and knack for covering the tracks of his influences), which Ayn Rand mythologized in the unendingly popular 1943 novel The Fountainhead. The Creative Architect appreciates the keen competition between top architects for commissions and other recognition, implicating these strivings in the genesis of creativity, but maybe doesn’t say enough about how, especially when prized, creativity—or the simulation of it—can also be exploited or even deliberately exaggerated as a strategic means to achieving power, influence, and domination. Again, Philip Johnson is a good example. Described by one study examiner as “a disciple of Mies, to the point of bearing the stigmata” (48, see also 78), Johnson exchanged this allegiance for a claim to Lloyd Wright’s legacy by strategically broadening the diversity of his designs.2 It is no wonder that despite harboring vast self-doubt, which both Mies and Lloyd Wright reinforced, Johnson boosted his creativity rating in the IPAR study by ranking himself first—as did Eero Saarinen, who also had a famous architect of a father, Elie Saarinen, with whom to compete.

Aspects of the architects’ personal histories that disturb more simplistic notions of creativity did not go unnoticed by IPAR investigators. Unfortunately, the presence of emotional conflict or turmoil in most study subjects seems to have allowed MacKinnon to embrace a particular cultural mythology that The Creative Architect unwittingly propagates: that “without some kind of psychiatric turbulence… one is not likely to grow creatively. In the creative personality, two usually opposed traits coexist: deep-rooted psychopathology and self-actualization” (219). In recent decades, the presumed yet never substantiated etiological link between psychiatric disturbance and creativity has blossomed into a veritable cottage industry that valorizes mental illness as a wellspring of generativity.3 But trauma and psychopathology are common, and plain old psychic conflict is ubiquitous—in architects, and in all people. Can these be channeled or sublimated in the service of driving creativity? Of course. But what allows one person to make creative use of this fuel, and not another person, is still a mystery. If, as Serraino claims, the IPAR study “lifted the fog surrounding the notion of genius” (214), then his book does little to clear the air.

On a final note, when reading The Creative Architect it is often unclear whether the author is merely repeating MacKinnon’s assertions about creativity, or whether he is drawing his own conclusions from the study data, leading this reader to wonder whether the book has a subconscious subtextual aim—to resurrect IPAR’s forgotten manuscript and reinstitute the study’s scientific panache. If so, it fails, just as the IPAR study failed to clarify creativity through the lens of science, for The Creative Architect’s greatest weakness lies in the romantic idealization of IPAR’s scientific value. The true value of the study—and the book about it—lies elsewhere. Just as the IPAR study’s importance as a cultural artifact eclipses its importance as a scientific contribution, the greatest strength of The Creative Architect is its thorough and often moving documentation of a critical cultural moment and the social and political forces that shaped it.

Figure 6. Eero Saarinen’s mosaics test, Creative Architect 127.

Endnotes:

Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz, Legend, Myth, and Magic in the Image of the Artist: A Historical Experiment, trans. Lottie M. Newman and Alastair Laing (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979 [1934]); also see Rosalind Krauss, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985).

Adele Tutter, Dream House: An Intimate Portrait of the Philip Johnson Glass House (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2016).

Adele Tutter, “Romantic Fantasies of Madness and Objections to Psychotropic Medication,” Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 57 (2009): 631-655.

Adele Tutter, MD, PhD, is Clinical Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Vagelos College of Medicine, and Faculty, Center for Psychoanalytic Training & Research, Columbia University; Faculty, New York Psychoanalytic Institute. Her interdisciplinary essays and books focus on psychoanalysis and culture. She maintains a private practice in psychiatry and psychoanalysis.