February 20, 2020-February 15, 2021

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Rem Koolhaas and Samir Bantal, directors; Troy Conrad Therrien, curator

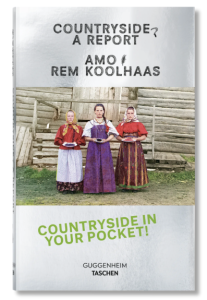

Although there are many critiques of Samir Bantal and Rem Koolhaas’s exhibition Countryside, The Future, perhaps there is only one critique of Koolhaas’s concept of the countryside: that there is no countryside at all. What and where is the “countryside” of the exhibition? Koolhaas and Bantal’s countryside includes a history of leisure, the dominance of the Cartesian grid, a thawing permafrost in Yakutsk, a dairy farm in the desert, modernist megaprojects in Eastern Europe, and even a gorilla preserve in Uganda. Their countryside seems only available through a negative definition: that which is not the city. The closest that Koolhaas comes to acknowledging this absence at the center of this exhibition is in the joke printed on the cover of the exhibition catalogue: “Countryside in your pocket!” How, after all, could you ever fit the countryside into your pocket when you can’t even fit it into a word?

I visited Countryside, The Future on February 29, 2020, on a crowded Saturday, before most people had a sense of how the coming months would unfold. The exhibition in the Solomon R. Guggenheim in New York ran from February 20, 2020 until February 15, 2021, and closed in between when the city shut down. Even though the show has now concluded, adjacent materials abound on the Guggenheim website in the form of images and podcasts, talks that Rem Koolhaas has given at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (archived on YouTube), and, of course, the exhibition catalogue. Countryside, The Future is bursting at its seams with information for anyone interested, though nothing I experienced at the Guggenheim, that last time I ventured into a crowded space, offered more than the catalogue and essays.

The exhibition is arranged from bottom to top in the Guggenheim’s spiral in distinct themes, each occupying one level. The “semiotics column,” a display of images from magazines collaged on the outer surface of the service-core of Wright’s building, argues that the countryside is an advertising fiction created by glamor shots and ideals of nature as a nostalgic refuge from the overstimulation of the city. This wall of images, argue the curators, prevents us from seeing the reality of the countryside, which is in fact a massive post-Enlightenment design project that includes river management in India, river reversal in Eastern Europe, Stalin’s countryside, and post-human industrial centers in Reno, Nevada. Where architects in the 20th century might have argued that the car on the highway was the emergent spatial experience of the future, Koolhaas seems to find the car and highway a barrier—a wall, like the semiotics wall, that prevented one from seeing the true infrastructure of modernity. Shuttling in the gray space between Rotterdam and Amsterdam, Koolhaas one day stops and steps out of his car to investigate what is behind this wall of a highway.1 What he discovers amazes him. Koolhaas discovers an uncontainable “real real” that can only be referred to by the empty, negative signifier of the countryside.2

The Guggenheim’s architecture curator, Troy Conrad Therrien, writes, “Countryside, The Future is not an art show but it’s also not a science exhibit. Nor an architecture exhibition. It’s a collection of stories told through case studies, global zooms, into an assortment of episodes, scientific, cultural, historical, futuristic.”3 This is the strength of the exhibit: it proposes an alternate form for the architecture-exhibition, one that doesn’t treat architecture as an artifact-producing practice but an information- and theory-producing one. It does this by placing a tractor and the replica of a mammoth alongside scanned and downloaded images, which, collaged together, propose alternate artifacts within the space of the museum.

Unfortunately, the quality of the copies and the carelessness of their display negate any real engagement with the form of a data-driven and conceptual architectural exhibit. One of the few photos I took at the show was of my 11-month-old attempting to scale a display with an image of Jawaharlal Nehru. The image bore Nehru’s name, signaling him as part of the exhibit, but his face was cropped out. Although this may seem like careless graphic design, this instance points to a larger absence where bothersome details—mainly the numerous people who perform manual labor on farms picking cotton and berries among other commodities—are excised, literally cropped out, in the interest of an aesthetic completion.

The three artifacts—the industrial sized bale of hay, the massive tractor out front, and the mammoth that emerged out of the permafrost in Yakutsk—make the case for what Koolhaas and Bantal seem most affected by: the staggering scale of the countryside. It is massive and overwhelming. Can that scale be replicated and experienced in the gallery? Can the industrial-agricultural be a kind of sublime? For the curators, this sublime authority was best demonstrated by “master-countrysiders” Hitler, Stalin, and Mao. Thus, life-sized cutouts of these men were placed on Roombas so they could roam the galleries. The contraptions featured a large red stop button for safety, which proved an attraction for children who made it their mission to hit. The robots thus ended up in awkward positions on the ramps and floor attendants found themselves dedicated to monitoring and restarting these gizmos. Thus, on the question of aesthetic judgment, this exhibit seemed to conform less to the Kantian category of the sublime and more to Sianne Ngai’s aesthetic theory of the gimmick, a commodity judged as having a mismatch between labor and effect—an overrated device that strikes us as working both too little and too hard.4 In fact, the entire exhibition felt like a gimmick.

At one moment in the large body of supporting material for the exhibition Koolhaas is quoted as saying “At this point, I barely feel like an architect, [more like] a journalist or an anthropologist.”5 This gets us to the core of the issue. The countryside has been transforming and so has the profession of architecture. The research interests of its practitioners are changing. Its aesthetic language has altered. Koolhaas is not on the cutting edge of that change, but is rather its last practitioner. This has been a change driven by architectural historians, who have thought long and deep about studying the kinds of archives that challenge the content of architecture. It has been driven by scholars who have shown concern for infrastructure, its politics, and its people. This change has been led by architects studying in anthropology and cultural geography departments who have devoted their scholarship to understanding the spatial lives of workers who migrate between village and workplace, and between countries, to labor on stadiums and skyscrapers, and in the countryside. By departments of people working in agrarian studies who explore the complicated politics that animate power across regions.

And this change has been led by studio cultures that show care towards climate change and the transforming earth. Every year, more students and faculty in architecture, landscape, and planning departments investigate infrastructural and regional spatial formations in their studios; architects have studied migrant labor and rural-urban conurbations, all of which push back against the city-country binary that Koolhaas and Bantal reinforce and reify. Koolhaas and Bantal speak loudly through their Guggenheim-shaped megaphone, amplifying a conversation that is ongoing in the extended architectural community.

Even then, they have missed the trend, which is the persevering scholarly dismantling of the city-country binary. Despite the formal and jurisdictional distinctions of the subject at hand, their countryside is a vacuous concept because city and country are fundamentally intertwined and can only be studied as such.

Notes

- Troy Conrad Therrien, “Along for the Ride,” in Countryside, A Report, ed. Rem Koolhaas and AMO (Cologne: Taschen, 2020): 12

- Slavoj Žižek, Looking Awry: An Introduction to Jacques Lacan Through Popular Culture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992): 14–15.

- Therrien, “Along for the Ride”: 13.

- Sianne Ngai, Theory of the Gimmick: Aesthetic Judgment and Capitalist Form (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2020): 1.

- Edwin Heathcote, “Rem Koolhaas: ‘The Word Starchitect Makes You Sound Like an A**hole,’” Financial Times, March 9 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/7180ef52-2198-11e8-a895-1ba1f72c2c11.

Ateya Khorakiwala is an architectural historian at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, researching infrastructure and aesthetics in India’s countryside during the developmental decades.

How to Cite This: Khorakiwala, Ateya. Review of Countryside, The Future, curated by Troy Conrad Therrien, directed by Rem Koolhaas and Samir Bantal, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 20, 2020 – February 15, 2021, JAE Online, May 21, 2021.