Review By: Victoria Bugge Øye

November 1, 2024

For many, a visit to the hospital will be the most traumatic experience of their life. When cancer patients recall entering bewildering hospital complexes, they talk about a feeling of degradation and loss of control. They describe an unbearable sense of narrowness, darkness, and crowding. They experience anxiety and breathing difficulties while waiting in windowless rooms. Basement therapy areas stir up “traumatic funeral nightmares.” These technologically sophisticated buildings, products of two centuries of Western medicine, are set up as a swift and sanitized system for moving as many sick bodies as possible. Illness and the possibility of death make us vulnerable; they can cause us to lose our sense of grounding in the world, self-determination and even sense of self. What if the spaces that are designed to treat and heal actually make us sicker?

Tanja C. Vollmer, an architectural psychologist whose research informs the exhibition Building to Heal: New Architecture for Hospitals, discovered precisely that: most of the patients she interviewed believed that the hospital made them feel sicker than they would have at home. Many respondents had such poor experiences in hospitals that they feared hospitalization more than the actual disease. Starting with these and similar observations made by other researchers, Building to Heal is an exhibition with a clear agenda: to reform health-care architecture. The exhibition curators position this as a new approach to hospital reform because its main focus is the experience and perception of these spaces by patients and next of kin rather than their technical and spatial performance.

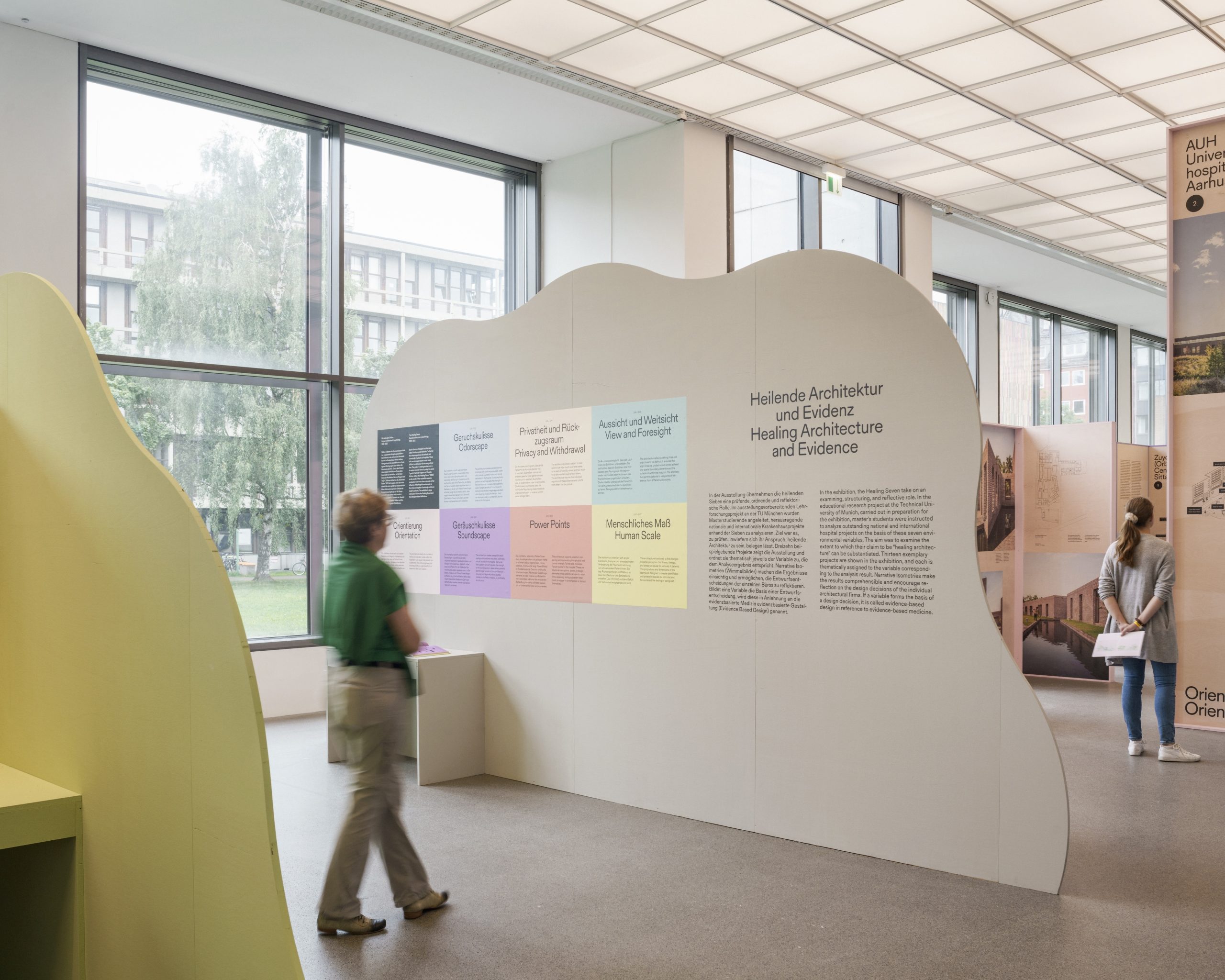

The exhibition’s narrative, which looks at hospital architecture in general and the German hospital system in particular, is anchored by something referred to as the “Healing Seven.” This is a set of seven variables, or architectural qualities, composed by Vollmer and architect Gemma Koppen, which they claim can help reduce patients’ stress response. When working in concord, these variables are supposed to result in what the exhibition refers to as “Healing Architecture.” They include orientation (architecture that allows the patient or visitor to intuitively understand routes and determine their own location), odorscape, soundscape, withdrawal and privacy (architecture that allows the patient to control their degree of exposure to others), power points (nonmedical spaces where patients can recharge and break up time), view and foresight (architecture that favors diverse sightlines), and human scale (architecture that accommodates the specific needs of seriously ill patients).

Figure 1: © Architekturmuseum der TUM, photo Sebastian Schels

Contrasting with the overtly technical and economic focus of contemporary hospital architecture, the exhibition proposes to introduce evidence-based design as an additional parameter for hospital design. The field of evidence-based design, which considers the psychological and physiological effects of architecture, is often traced back to Roger S. Ulrich’s 1984 article “View Through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery,” which found that patients recovered better and faster when they had access to a view of natural surroundings. That environmental factors can promote healing is one of the main assertions made in the show. But as we learn from Vollmer’s fascinating research, this becomes especially pertinent for health-care buildings, as severe and long-term illness can also cause spatial distortion and disorientation. Disease and psychological stress can induce measurable changes in a person’s ability to orient themselves in space and time. They can become more sensitive to sound and smells, and experience spaces as longer, narrower and darker. These are subjective experiences that, she argues, should have ramifications for design.

Figure 2: © Architekturmuseum der TUM, photo Sebastian Schels

The exhibition design is inviting, quirky, and fresh. Cloud-shaped half-walls in chalky pastels and raw plywood partition the airy and light gallery space. Each of the “Healing Seven” is organized in a cluster of a unique color. At times the design of the walls parrots the theme; for “Privacy,” a wall bends inward to form a niched seating area, cupping the visitor. Graphics depicting contextual, geographical, and demographic information on German health care (including its multipayer insurance system) appear throughout the installation. One wall graphic illustrates a historical trajectory that includes the midcentury therapeutic revolution, the increasingly large, complex, and centralized “medical centers” of the 1980s, the turn to “patient-centered” approaches from the 1970s and onward, and today’s trend toward hospital consolidation and outpatient care. In Germany as elsewhere, there is an urgency to this trajectory; with aging infrastructure, financially insolvent institutions, labor shortages, and a lack of pediatric care facilities, what do Germans want the hospital of the future to look like?

Figure 3: © Architekturmuseum der TUM, photo Sebastian Schels

The idea of the “Healing Seven” is also illustrated by thirteen built hospital projects that have been analyzed by students from the Technical University of Munich (TUM), the museum’s affiliate institution where Vollmer has taught a class on health-care architecture. The projects, most of which are located in Germany and Denmark and have been completed in the past two decades, are depicted in models, photographs, plans and “narrative isometries”: drawings that include representations of patients, next of kin and health-care workers, whose imagined experience of the spaces are given voice through narrative and speech boxes. One of the boxes blurts out “only Tina, Tom, Teddy and me!” to illustrate withdrawal and privacy in the Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology in Utrecht. According to the catalog, the projects are selected because they are “outstanding” examples of healing architecture, which the analyses, conducted by TUM students, set out to substantiate. None are, to my knowledge, based on evidence-based design. It remains unclear why exactly these hospital buildings were chosen and what their relationship is to the “Healing Seven.” Can a building be outstanding without evidence-based design? In addition, Vollmer’s strong emphasis on subjective sensory experience is not done justice with the fairly traditional architectural analysis and case study presentations, which are uniformly applied regardless of the qualities they are called in to represent. Two installations by smell-artist Sissel Tolaas (a rub and sniff wall and a set of curtains, both imbued with “healing” smells) bookend the show and provide an intriguing gesture toward the potential of Vollmer’s research. Regardless, the exhibition impresses in its ability to condense and present vital research to a general and nonspecialist audience with a clear ambition and call for change.

Figure 4: © Architekturmuseum der TUM, photo Sebastian Schels

Figure 5: © Architekturmuseum der TUM, photo Sebastian Schels

In the exhibition this call for change is strategic and directed towards a single goal: hospitals. This well-defined scope makes for a tightly curated show with a clear message. But with increased emphasis on outpatient care, aging populations, lifestyle diseases, and stress- and anxiety disorders, the hospital is only one of many spaces where “healing” takes place. Unfortunately, in the seemingly clear-cut objectivity of evidence- and neuroscience-based design, issues of spatial and environmental justice are often left out. To be a patient, as Michel Foucault and others have argued, is to experience the separation of one’s body from one’s person; it is a form of alienation. But to be cared for is also a position of privilege that is not accessible to all. One enemy of healing might be the technical regime of the German hospital machine, with its antiseptic surfaces and windowless corridors, but this is simply one piece of a much larger beast. For researchers such as Vollmer who work on “spatial diseases,” a more pronounced alliance with spatial and medical justice might be the way forward, with an understanding of how medical care is distributed across lines of geography, class, race and so on. Recent critical disability scholarship by Jos Boys, David Gissen and Aimie Hamraie—briefly referenced in the rich catalog—can lead to a broader shift in the way that bodies and architecture are negotiated. The hospital, after all, is only one—albeit central—node in a larger network of spaces, infrastructures and communities in the lives of people with chronic and severe illness. In this sense, reforming the hospital is only the beginning.

Victoria Bugge Øye is senior curator of modern architecture at the National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design in Oslo. Her research focuses on the intersections of post-1945 American and European architecture with the discourses of science, medicine and psychology. She holds a PhD in the History and Theory of Architecture from Princeton University.