Joy Knoblauch

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020

From a profusion of earnestly tooth-clenched pipes waggling over hundreds of government-funded design revisions to an exchange of frustrated expletives and cool concern in what one can only imagine is an Ivy-league lecture hall, Joy Knoblauch’s new book, The Architecture of Good Behavior: Psychology & Modern Institutional Design in Postwar America traces a history of the relationships between scientific credibility, government funding, good intentions, and architecture’s societal relevance. All of this orbits an evolutionary inquiry into the built environment’s capacity to influence people’s mental health through institutional and urban design, for better or worse. Knoblauch calls this tendency “psychological functionalism.”

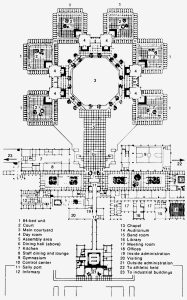

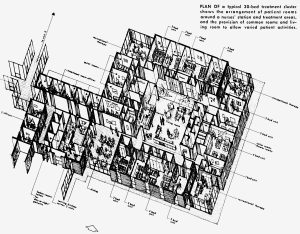

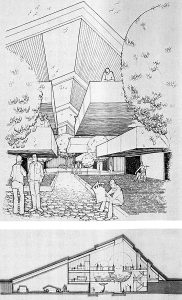

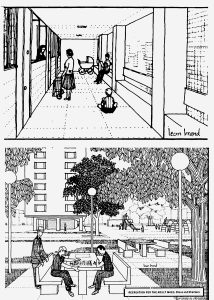

A series of case studies in institutional design, urban design, and research entity development describe the way that psychological functionalists in the postwar period followed their scientific collaborators into a loose understanding of—but firm belief in—the ways that the built environment can impact human well-being, especially mental health. The first two case studies describe architects as businesslike partners of community and the “franchise state.” Partially funded under government legislation such as the Hill-Burton Act, these case studies examine the development of two networks of small-scale institutions: the construction of approachable and overtly budget-aware community hospitals and then a network of community mental health centers (CMHCs), which were realized to a lesser extent than their earlier cousins. The following chapter on open prison design sees architects aspiring to reform the prison experience through psychology and spatial design, eventually splitting into those who continued to design prisons, albeit with fewer “overt discussions of power and manipulation” (129), prison abolitionists, and many in between. As open examination of behaviorally meaningful architecture—in instances of hierarchical power such as prisons—waned, the next case study shows the way that Oscar Newman’s ideas about defensible space developed amidst rising fears of violent crime rooted in racist nostalgia for the segregated past. As if a context of fear were not enough, Knoblauch also outlines the way that Newman used other powerful tactics and tools to spread his ideas. Quasi-scientific data, gestural diagramming, architectural visualization, and an entrepreneurial approach (including the development of a board game) served as effective conduits for the proliferation of defensible space ideas into the canon of environmental design. In a state of existential crisis, the funded investigation of “psychological functionalism” finally diffuses into an array of architecture schools in the form of novel research entities such as the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS) and the Environmental Design Research Association (EDRA).

Through these case studies, Knoblauch tracks the courtship between design and psychiatric well-being that arose from architects’ attraction to the promise of quasi-scientific credibility that might be obtained through partnership with the social sciences, especially psychology. This discipline was rapidly becoming installed as an essential component of mass democratic control through the establishment of entities like the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Knoblauch consistently triangulates government funding, architects’ struggle for continued relevance amidst the rise of modern medical science, and the apparent “innocence” of architecture. The haunting capacity of this set of relationships to cloak mechanisms of biopolitical power helps the reader maintain an appropriate skepticism toward an underexplored history that may have been protected from interest in the past by its altruistic appearance.

To this point, The Architecture of Good Behavior dovetails neatly with Jeanne Kisacky’s 2017 book Rise of the Modern Hospital: An Architectural History of Health and Healing (also published by the University of Pittsburgh Press). Together, the two books flesh out 100 years of health institutional design, the governmental, professional, and economic partnerships that structure that history, and the curious call-and-response between design development and medical/pharmacological procedure. This is all in relation to an evolving view of patient identity—what we might call proto-inclusion. There is a tension here between the good intentions of the institutions and designers and the need for architectural environments to reiterate the calm and control that allow health “misfits” (people with mental illnesses especially) to be governable—if not productive—members of society by the measures of their day. Good Behavior meets Rise of the Modern Hospital almost seamlessly, picking up on the story of the hospital design and construction projects funded under the Hill-Burton Act, as Knoblauch herself acknowledges early in the book.

In the end, Knoblauch notes that even as architects’ interest in psychological functionalism seemed to plateau and curl inward we still see persistent influences of this movement in the form of evidence-based design practice. Information about how the physical environment impacts the psyche has rooted itself in common knowledge. One need look no further than science journalist Emily Anthes’ 2020 book The Great Indoors: The Surprising Science of How Buildings Shape Our Behavior, Health and Happiness for a contemporary view of the ways that psychological functionalism thrives in the attention of a more general audience, especially among design-conscious health and clinical professionals who acquire more design credibility by the day. For more on this growing legitimacy, see Bon Ku and Ellen Lupton’s 2020 book Health Design Thinking: Creating Products and Services for Better Health.

The Architecture of Good Behavior is important for those whose work focuses on trajectories of care and the interaction of the built environment and human well-being, as well as for scholars of environmental behaviorism and evidence-based designers and researchers from all disciplines who operate at the boundaries between human health and design. The chapters that explore prison design research in the 1960s and 70s (chapter 3) and the development and adoption of defensible space ideas (chapter 4) will be especially useful for architects, activists, and educators who examine and advocate for social justice transformation including calls for the expunging of defensible space principles from the Architect Registration Examination (ARE). All readers will benefit from the way this history illuminates ingrained racism and assumptions about governability that persist within architecture today.

Trudy Watt is an architect and educator working on matters of architectural process, social inclusion, health equity, and compassionate interdisciplinary pedagogy in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In addition to teaching design fundamentals, she researches creative ways to build care theory into design and equity into the built environment. Her current work connects architecture to the fields of gerontology, healthcare, entrepreneurship, storytelling, activism, organizational dynamics, and applied compassion. She is an assistant professor at the School of Architecture and Urban Planning and a teaching fellow at the Lubar Entrepreneurship Center at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

How to Cite This: Watt, Trudy. Review of The Architecture of Good Behavior: Psychology & Modern Institutional Design in Postwar America, by Joy Knoblauch, JAE Online, May 7, 2021.

All images furnished by the University of Pittsburgh Press.