“The future belongs to Africa,” claims the Nigerian-born curator Okwui Enwezor, “because it seems to have happened everywhere else.” This cunning statement combines hope and forbearance, reflecting the challenges postcolonial Africa is facing in the context of post–Cold War geopolitics. These days Africa attracts an increasing number of investors, artists, and scholars. They see it as fertile soil for profit making, creative experimentation, and frugal innovation. However, as Enwezor complains, over the last decades Africa has been described as the place where people survive on less than one dollar per day. This relentless insistence on Africa’s poor performance in statistical accounts of its wealth casts a gloomy shadow over the whole continent. “Do Africans ever get a raise? Can it be please a dollar-fifty? Is there no inflation?” asks Enwezor. And rightly so. There is some sense of urgency in shifting the one-dollar-per-day narrative to something more hopeful.

There are two aspects that deserve further intellectual scrutiny to underpin the possibility of an African Renaissance. First, we need to reconceptualize the creative potential of informality. In a world where cities will play an increasing role as the backdrop for our collective existence, we have to think about informality as a new way of life, as Nezar Al-Sayed put it.1 Second, we need to harness the productive potential embedded in the invisible infrastructures that activate vernacular social and spatial practices. As AbdouMaliq Simone contends, we need to look at people as infrastructure rather than the tangible systems of highways, pipes, wires, or cables.2

These two aspects have achieved a great deal of prominence in the way Africa has been portrayed in recent high-profile conferences, publications, and exhibitions. The famous Design Indaba festival (http://www.designindaba.com/), organized since 1995 in Cape Town (South Africa), is arguably the most notable venue for African artistic creativity, in general, and for designers in particular. Design Indaba bluntly rejects a parochial approach in its program and activities.3 However, while it is focused on global design, Design Indaba is a major showcase for African creativity, featuring the work of leading artists, public intellectuals, opinion makers, and industry experts.

On the opposite coast of Africa, another well-known educational institution, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH-Zürich), started in the mid-2000s an academic collaboration with the so-called Building College at Addis Ababa University.6 This collaboration would accelerate the transfer of knowledge from both parts. The results of the first “urban laboratories” coordinated by Marc Angélil and Dirk Hebel were published in Cities of Change: Addis Ababa and showed the need to explore alternative approaches to the current exploitation of urban territories in developing countries such as Ethiopia.7 Over the last decade these kinds of partnerships between academic institutions from the global North and their counterparts from the global South have been gaining momentum and contributing to the emergence of new pedagogical methods in architectural education.8

Some of these academic partnerships created tangible outcomes. The figure of the “design-build” studio became a popular pedagogical approach to the exchange of knowledge between North and South. Popularized by the famous Rural Studio program of the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture at Auburn University, this pedagogical approach was particularly praised by schools from German-speaking countries. A selection of notable examples was shown in the exhibition Afritecture: Building Social Change, curated by Andres Lepik and Anne Schmidt with Simone Bader. This exhibition, held at the Architekturmuseum der TU München in the autumn of 2013, highlighted the work of twenty-nine teams and offices working in ten different sub-Saharian countries. Most of the buildings shown were small-scale developments, initiated by educational institutions or NGOs.9 While Afritecture revealed interesting contributions to help us rethink the knowledge transfer between vernacular social and spatial practices and contemporary architectural approaches, it fell short in dealing with the “great number.” Indeed, coping with the sheer magnitude of the figures associated with the urbanization process currently unfolding in Africa remains one of the greatest challenges to the design disciplines in general, and architecture in particular.

The growing interest of cultural institutions from the global North in African design was once again visible in the exhibition Africa: Architecture, Culture and Identity. The Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, one of the most prestigious Danish cultural venues, organized this exhibition, which was held in the summer of 2015. In the exhibition’s opening speech, the Ghanaian architect and president of ArchiAfrica, Joe Osae-Addo, highlighted an important paradigm shift happening today. “For the first time in my living memory,” Osae-Addo asserted, “there are African artists, architects, musicians and other creatives, who can engage at the higher level and have the work to back it up.” In the exhibition’s catalog, the Cameroonian historian and philosopher Achille Mbembe stresses the importance of this paradigm shift. “Like it or not,” Mbembe argues, “there no longer exists a center to which we can oppose a periphery.” And he goes further asserting that “to become a protagonist in the birth of this new world history, planetary but decentred, Africa needs to rewrite itself.”10

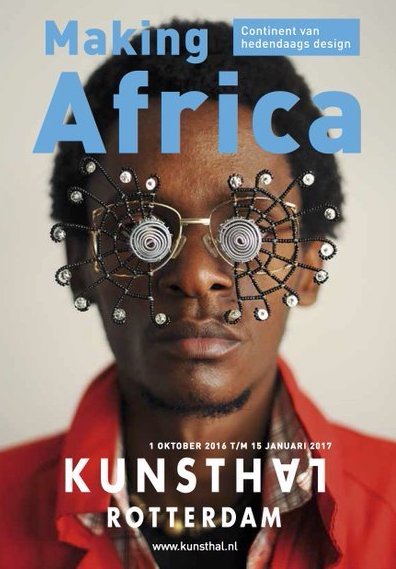

These events, pedagogical initiatives, books, and exhibitions have highlighted Africa’s multiplicity. They have contributed many illustrations to Africa’s signature feature: its social and cultural polytheism, as Mbembe put it. It is against this intellectual background that African design is presented and discussed in Making Africa—A Continent of Contemporary Design, an exhibition produced by the Vitra Design Museum and the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, and curated by Amelie Klein under the direction of Mateo Kries and Marc Zehntner. The curators have outlined an ambitious goal for the exhibition. They aim at encouraging contemporary artistic production that goes beyond the clichés associated with African design, usually based on a spectrum of concerns around recycling, traditional craft, or humanitarian design. To accomplish this aim, the 134 artworks and interviews displayed in Making Africa emphasize the importance of two key conceptual approaches in African design: accommodating the informal and making the invisible visible.

The exhibition has been on the road for some time now. It first appeared at the Vitra Design Museum, in Weil am Rhein, Germany (March 14–September 13, 2015). Then it moved farther south to Spain, appearing at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao (October 30, 2015–February 21, 2016) and then at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (March 22–July 31, 2016). The most recent venue for the exhibition was the Kunsthal in Rotterdam (October 1, 2016–January 15, 2017). The exhibition’s website (http://makingafrica.net/) lists future venues.

The second section of the exhibition, “I and We,” focuses on depicting instances of African lifestyle. Not ordinary impressions of urban or rural everyday practices, though. Instead, powerful images associated with a certain aesthetic bravura. The curatorial approach to this section shows a striking similarity to Bernard Rudofski’s 1944 exhibition, Are Clothes Modern? held at the Museum of Modern Art. As in Rudofski’s show, in this section, the curators of Making Africa seem to be interested in displaying the remarkable nexus between the vernacular tradition and the avant-garde. In other words, as the clever highlight of a review of Are Clothes Modern? published in Life Magazine in 1946 put it, there is an implicit suggestion in “I and We” that “for every modern style there is a jungle counter part” (Figure 2).11 The project for the Chicoco Radio building designed by Kunlé Adeyemi and his practice NLÉ testifies to the overwhelming tensions between the native social and spatial fabric and the desire for modernity (Figure 3). One feels like asking, Is the Chicoco Radio building modern?

The second section of the exhibition, “I and We,” focuses on depicting instances of African lifestyle. Not ordinary impressions of urban or rural everyday practices, though. Instead, powerful images associated with a certain aesthetic bravura. The curatorial approach to this section shows a striking similarity to Bernard Rudofski’s 1944 exhibition, Are Clothes Modern? held at the Museum of Modern Art. As in Rudofski’s show, in this section, the curators of Making Africa seem to be interested in displaying the remarkable nexus between the vernacular tradition and the avant-garde. In other words, as the clever highlight of a review of Are Clothes Modern? published in Life Magazine in 1946 put it, there is an implicit suggestion in “I and We” that “for every modern style there is a jungle counter part” (Figure 2).11 The project for the Chicoco Radio building designed by Kunlé Adeyemi and his practice NLÉ testifies to the overwhelming tensions between the native social and spatial fabric and the desire for modernity (Figure 3). One feels like asking, Is the Chicoco Radio building modern? “Space and Object,” the third section of the exhibition, presents the city as the locus where the challenges to the construction of a new African identity are more clearly perceived. Buildings and cityscapes are placed next to technological innovations such as the mobile money transfer system M-Pesa. This scenographical strategy illustrates how constraints can be instrumental in activating creative solutions. Indeed leapfrogging—for better or worse—the technological advancement in the global North. The surreal landscapes created by Justin Plunkett’s Con/Struct series stress the tensions between informality and technological advancement. In Plunkett’s digital photomontage Skhayascraper, shacks built with corrugated metal sheets—arguably the most notorious material associated with urbanization in Africa—are piled up to create a sophisticated high-rise building (Figure 4). The result is a fictional figure that could easily have been designed by the likes of Morphosis or Coop Himmelblau.

“Space and Object,” the third section of the exhibition, presents the city as the locus where the challenges to the construction of a new African identity are more clearly perceived. Buildings and cityscapes are placed next to technological innovations such as the mobile money transfer system M-Pesa. This scenographical strategy illustrates how constraints can be instrumental in activating creative solutions. Indeed leapfrogging—for better or worse—the technological advancement in the global North. The surreal landscapes created by Justin Plunkett’s Con/Struct series stress the tensions between informality and technological advancement. In Plunkett’s digital photomontage Skhayascraper, shacks built with corrugated metal sheets—arguably the most notorious material associated with urbanization in Africa—are piled up to create a sophisticated high-rise building (Figure 4). The result is a fictional figure that could easily have been designed by the likes of Morphosis or Coop Himmelblau. The resonances of Africa’s urban challenges with those in other parts of the global urban South are distinctly expressed in Mikhael Subotzky’s and Patrik Waterhouse’s monumental mosaic of pictures taken inside and outside the highest residential building in Africa, Ponte City, located in Johannesburg. The trajectory of Ponte City from a fashionable address in the Apartheid era to a derelict structure today bears noticeable similarities with the infamous Torre David built in the early 1990s in Caracas, Venezuela. Like Ponte City, Torre David started as a celebration of the power of the few and ended up as an “informal vertical community,” as Urban Think Tank euphemistically called it.12 Subotzky’s and Waterhouse’s patient photomontage of domestic landscapes (both virtual and real) in the fifty-four stories of Ponte City is a poetic translation of the boundaries that separate and define the identities of the fifty-four nation-states on the African continent (Figures 5–7).

The resonances of Africa’s urban challenges with those in other parts of the global urban South are distinctly expressed in Mikhael Subotzky’s and Patrik Waterhouse’s monumental mosaic of pictures taken inside and outside the highest residential building in Africa, Ponte City, located in Johannesburg. The trajectory of Ponte City from a fashionable address in the Apartheid era to a derelict structure today bears noticeable similarities with the infamous Torre David built in the early 1990s in Caracas, Venezuela. Like Ponte City, Torre David started as a celebration of the power of the few and ended up as an “informal vertical community,” as Urban Think Tank euphemistically called it.12 Subotzky’s and Waterhouse’s patient photomontage of domestic landscapes (both virtual and real) in the fifty-four stories of Ponte City is a poetic translation of the boundaries that separate and define the identities of the fifty-four nation-states on the African continent (Figures 5–7). The final section of the exhibition, “Origin and Future,” denotes a curatorial approach suggesting interdependences between Africa and the world system in many different realms. There is room for the anecdotal history of the ubiquitous fabric known as Dutch Wax. There is also space dedicated to fashion designers and artists who explore the creative potential of using poor and feeble materials to produce rich and powerful results. This is illustrated masterfully by a dress designed by Oumou Sy, Senegal’s “Queen of Couture.” The dress from Oumou Sy’s Bour Sine—Hommage à Senghor collection featured in the exhibition explores Léopold Sédar Senghor’s concept of métissage as inspiration for the striking combination of different materials and production techniques used to create the dress (Figure 8).

The final section of the exhibition, “Origin and Future,” denotes a curatorial approach suggesting interdependences between Africa and the world system in many different realms. There is room for the anecdotal history of the ubiquitous fabric known as Dutch Wax. There is also space dedicated to fashion designers and artists who explore the creative potential of using poor and feeble materials to produce rich and powerful results. This is illustrated masterfully by a dress designed by Oumou Sy, Senegal’s “Queen of Couture.” The dress from Oumou Sy’s Bour Sine—Hommage à Senghor collection featured in the exhibition explores Léopold Sédar Senghor’s concept of métissage as inspiration for the striking combination of different materials and production techniques used to create the dress (Figure 8). Senghor, a poet and philosopher who became the first president of Senegal in 1960, believed in cultural hybridization as a condition to achieve a great world civilization, tolerant and inclusive. There is a clear parallel in Senghor’s métissage with the concept of cultural cannibalism brought about in 1928 by the Brazilian modernist poet Oswald de Andrade in his Manifesto Antropófago (Anthropophagic Manifesto, also known in the translation to English as Cannibalist Manifesto).13 Both Andrade and Senghor denounce the binary polarities civilization/barbarism, modern/primitive, and original/derivative, which pervaded the construction of the cultural identity in their countries since the colonial days. As Leslie Bary, the translator of Oswald de Andrade’s manifesto into English puts it, “Oswald’s anthropophagist … neither apes nor rejects European culture, but ‘devours’ it, adapting its strengths and incorporating them into the native self.”

Senghor, a poet and philosopher who became the first president of Senegal in 1960, believed in cultural hybridization as a condition to achieve a great world civilization, tolerant and inclusive. There is a clear parallel in Senghor’s métissage with the concept of cultural cannibalism brought about in 1928 by the Brazilian modernist poet Oswald de Andrade in his Manifesto Antropófago (Anthropophagic Manifesto, also known in the translation to English as Cannibalist Manifesto).13 Both Andrade and Senghor denounce the binary polarities civilization/barbarism, modern/primitive, and original/derivative, which pervaded the construction of the cultural identity in their countries since the colonial days. As Leslie Bary, the translator of Oswald de Andrade’s manifesto into English puts it, “Oswald’s anthropophagist … neither apes nor rejects European culture, but ‘devours’ it, adapting its strengths and incorporating them into the native self.”Oswald Castro’s Anthropophagic Manifesto seems to be hovering over in Making Africa. In one of the interviews featured in “Prologue,” the exhibition’s advising curator, Okwini Enwezor, claims that we need to find new terminologies and new strategies to communicate the qualities of African design.

On the one hand, Enwezor believes that accommodating aspirations and fostering collaborations should be used to help designers create a new toolbox for everyday users. On the other hand, he argues that the search for authenticity should be challenged. Instead, he suggests cultural consumption as an anthropophagist act, an active way of “ingesting something that may be seen at first as incompatible with one’s cultural milieu. … An active way of breaking down and reinvesting the power of the consumer with a new potency.”14 Making Africa—A Continent of Contemporary Design brings together compelling examples of a design ethos that resonates with Enwezor’s position. The narrative created by the assemblage of such diverse forms of cultural production as those featured in the exhibition can be seen as an Anthropophagic Manifesto for Africa. The exhibition also shows that there is no shortage of talent in Africa and in the African diaspora to make this manifesto a trigger to inscribe African contemporary design as part and parcel of a continuous negotiation of local cultures and universal civilization, as Paul Ricoeur would put it.15

How to Cite this Article: Mota, Nelson. “An Anthropophagic Manifesto for Africa,” review of Making Africa – A Continent of Contemporary Design, curated by Amelie Klein under the direction of Mateo Kries and Marc Zehntner. The Kuntsthal, Rotterdam, Netherlands, October 1, 2016 – January 15, 2017. JAE Online. May 6, 2017. http://www.jaeonline.org/articles/reviews-exhibits/anthropophagic-manifesto-africa#/.