September 28, 2019-January 5, 2020

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, St. Louis

Sabine Eckmann, curator

The thoughtful and provocative exhibition Ai Weiwei: Bare Life foregrounded the controversies and contradictions that animate the work of Ai Weiwei, a protean artist twice named the most influential artist in the world.1 In collaboration with curator Sabine Eckmann, Ai chose to display a modest number of things, yet still managed to include a diverse range of sculptural objects, photographs, and videos, dating from the mid-1990s through 2019.

Dividing this body of work into two separate galleries, the curators identified themes that have preoccupied Ai Weiwei. Dubbed a “Twitter bodhisattva” by one of his followers, Ai Weiwei has since 2008 devoted himself to resisting China’s Party-state authorities and drawing attention to humanitarian crises around the world, while endeavoring, he has claimed, to awaken people to the absurdity of life.2 The gallery titled “Bare Life,” a term derived from the writings of Giorgio Agamben, exhibited work that represented the plight of the disempowered, in particular the thousands of schoolchildren killed in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake—Forge Bed Rebar and Rebar (2008–12); Rebar and Case (2014)—and the countless refugees who have fled wars in the Middle East: Odyssey and Tyre (2016).

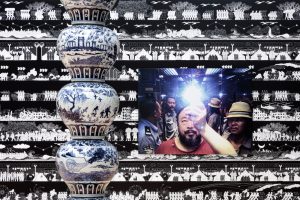

By contrast, the gallery titled “Rupture” displayed work that represented the consequences of the social and economic changes that have altered contemporary Chinese life and displaced its historical past: the stone feet chipped away from Buddhist figural sculptures, Feet (2010), and wallpaper composed of 128 photographs of demolished urban neighborhoods all over China: Provisional Landscapes (2002–8). Recognized for the wit of his conceptual artwork, Ai Weiwei has since the mid-1990s reconfigured artifacts from China’s historical past to disturb the complacency or indifference with which they have been viewed.

Each gallery was dominated by a structure that embodied the two curatorial themes. “Bare Life” was dominated by an arch constructed of 720 stainless steel bicycle frames aligned in a complex arrangement of units of six repeated 120 times (figure 2). Titled Forever Bicycles (2012), the mesmerizing arch cut across the gallery and extended toward the ceiling, creating a moiré effect in three dimensions. The arch was also a gateway, which echoed the conditions of movement, displacement, and death that Ai represented on the black-and-white wallpaper, the porcelain vessel-sculptures, and the marble replicas that surrounded the arch. The Forever bicycle frame itself called to mind an earlier work titled Very Yao (2009), which memorialized the execution of a drifter named Yang Jia, who, after being arrested in Shanghai for riding an unregistered bicycle, attacked and killed several police officers in retaliation.3

“Rupture” was dominated by Through (2007–8), an enormous structure built with heavy wooden beams, salvaged from an old temple (figure 3). The beams haphazardly crisscrossed as they extended toward the ceiling. With mathematical precision, their weight was supported by ends that touched the ground. Ten old decorated tables, scattered around the periphery of the structure and roughly hewn to fit the beams that seemed to pierce their surfaces, demarcated the boundaries of the open structure. Standing under its broken beams, I was uneasy, for this primordial canopy was also a ruin. In its precarious yet upright state, Through complemented the act of rejuvenation through destruction that was repeated throughout “Rupture,” notably in the old wooden bed, a site of procreation carved with auspicious signs yet entombed in the rubble salvaged from Ai’s destroyed Shanghai studio: Souvenir from Shanghai (2012).

A contrast between the materials featured in the two galleries further distinguished them and reinforced their respective evocations of death and rejuvenation. On the one hand, “Rupture” presented a culture of wood, a culture of hand-made objects, exemplified by the capacious Through (figure 4). On the other hand, “Bare Life” presented a culture of metal, a culture of the machine that reproduces things on an industrial scale, exemplified by Forever Bicycles. This was a compelling juxtaposition, for in the ancient Chinese system of the Five Processes (wuxing), metal and wood were considered a pair: metal was associated with the West and the season of autumn, a time of drawing in, whereas wood was associated with the East and the season of spring, a time of coming to life.4 Accordingly, the western gallery, “Bare Life,” was haunted by death. The bicycle frames recalled the execution of a drifter; the refugees figured on the black-and-white wallpaper were surrounded by soldiers and armored vehicles. The bombs meticulously delineated on the wallpaper that covered the outside of this gallery were designed to kill (figure 5). Conversely, the eastern gallery, “Rupture,” demonstrated regeneration. Lifeless wooden stools formed a cluster of imagined fruit in Grapes (2015), and an earthenware pot from the second century CE gained another life outside the tomb once the words “Coca-Cola” were inscribed on its surface: Coca-Cola Vase (2015–18).5

Despite the binary oppositions that distinguished the exhibition’s two galleries, it was also clear that they have much in common. I found striking the unsentimental and disinterested gaze that Ai Weiwei cast on destruction and human misery. Consider the black-and-white wallpaper titled Odyssey (2016), which covered two sides of the gallery “Bare Life.” Video projectors affixed to the walls distracted from the pictures of war presented on their surfaces. Some of the figural groups depicted in the frieze-like wallpaper were overlapped and shown in arrested motion, thus made to resemble figures that appear on Assyrian stone palace reliefs. These refugees evidenced no emotion and elicited no emotion. The violence characteristic of many Assyrian stone reliefs was dissipated. Similarly, the burdened figures pictured in blue pigment on a porcelain plate called The Journey (2017) were inevitably entangled with the ghostly images of stylized flowers and scenes from operatic plays that ordinarily decorated the surfaces of ancient blue-and-white porcelains. The strands of barbed wire depicted on the plate’s underside lost their point. A similar distance was cultivated in images of destruction shown in “Rupture.” Theatricality and resignation characterized The Crab House (2015), which starred Ai Weiwei’s assistants in conversation with local government officials. After having condemned Ai’s newly built studio in Shanghai, the officials were handed papers to sign, while cigarettes dangled from their mouths. The documented routine allowed little room for affective response.

Figure 4. Detail of Through, 2007-8.

Figure 5. Foreground: Bombs, 2019.

Yet, within each gallery, the juxtaposition of objects and videos generated new and unexpected understandings of Ai Weiwei’s work and, in particular, his reiterations of earlier projects. Replication became something other than a playful variation; the process became a means by which the artist has made and remade images of himself. Perhaps most intriguing in this regard was the re-presentation of one of Ai Weiwei’s most famous images, appropriately displayed in “Rupture”: Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (2015) (figure 6). In 1995, Ai was photographed three times: holding an old earthenware vessel in his hands, letting it then drop out of his hands, and finally showing it shatter on the ground at his feet.6 These very same photographs were reproduced twenty years later with hundreds of Lego bricks, colored in white and various shades of gray.7 The resulting image was out of focus, verging on invisibility. Twenty years ago, Ai Weiwei may have broken the earthenware vessel to demonstrate that it possessed greater value shattered at his feet than it had when left intact as an excavated grave good lost among hundreds of others in an antiquities market in Beijing. In the context of the acts of destruction featured in “Rupture,” breaking the Han Dynasty urn was analogous to the demolition of urban neighborhoods. But can it be that Ai Weiwei began to erase his portrait as he remade himself in a self-imposed exile, which began with his departure from China for Berlin in 2015? Last year, he announced that he would be moving to England. Adrift, he has identified himself as a refugee.

Figure 6. Foreground: Feet, 2010. Background: Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 2015.

Endnotes:

- See Art Review (2011–12), cited in Giorgio Strafella and Daria Berg, “‘Twitter Bodhisattva’: Ai Weiwei’s Media Politics,” Asian Studies Review 39, no. 1 (2015): 138, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2014.990357.

- Strafella and Berg, “‘Twitter Bodhisattva.’”

- Since 2003, Ai has worked with bicycle frames with and without wheels and seats, inscribed with and without their manufacturer’s name “Forever” (Yongjiu). See Sabine Eckmann, “On Becoming Visible,” in Ai Weiwei: Bare Life, ed. Sabine Eckmann (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 48–50.

- A. C. Graham, Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China (Lasalle, IL: Open Court, 1989), 340–56.

- Kristina Kleutghen made a similar point in “Rejointing Past and Present: Classical Chinese Woodworking and Ai Weiwei’s Furniture-Sculpture,” in Eckmann, Ai Weiwei, 111. I push this insight in a different direction.

- For Ai Weiwei’s engagement with potteries of various kinds, see Ai Weiwei: Dropping the Urn (Ceramic Works, 5000 BCE–2010 CE) (Glenside, PA: Arcadia University Art Gallery, 2010).

- In 2016, Ai Weiwei’s use of Lego bricks was denounced by the Danish company that manufactures the children’s building blocks, but public outcry forced the company to reverse itself. See https://www.bbc.com/news/world-35299069. Ai continues to use Lego bricks. For instance, in April 2019, he supervised the production of Lego-portraits of Mexican students who were reportedly massacred in 2014. See https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-47907840.

Credit for all images: Ai Weiwei: Bare Life, installation view, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, 2019. All photos by Joshua White / JWPictures.com.

Anne Burkus-Chasson (PhD, University of California, Berkeley, 1987) writes about seventeenth-century Chinese paintings and woodblock-printed books. Her articles, several of which have been translated into Chinese, have appeared in the Art Bulletin, Art History, and the Journal of Chinese Literature and Culture. Her book, Through a Forest of Chancellors: Fugitive Histories in Liu Yuan’s Lingyan ge, an Illustrated Book from Seventeenth-Century Suzhou, was published by the Harvard University Asia Center, Harvard University Press, in 2010. She was a Senior Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, in 2017–18. She is currently writing a book tentatively titled “Chen Hongshou (1598–1652) and the Illustrated Book.”

How to Cite This: Burkus-Chasson, Anne. Review of Ai Weiwei: Bare Life, curated by Sabine Eckmann, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, St. Louis, September 28, 2019 – January 5, 2020, JAE Online, February 7, 2020, http://www.jaeonline.org/articles/review/ai-weiwei-bare-life#/.