The Playground Project (Figure 1), now part of the

2013 Carnegie International, has a potent message for architects and landscape architects. Curator Gabriela Burkhalter exhibits playgrounds from the 1940s to 1970s in order to highlight the dearth of engaging play spaces today, especially in America. Burkhalter is very firm in urging designers to look to past successes in order to be inspired and to consider how today’s playground—which she rightly deems “standardized” and “sanitized”—could become again a significant addition to public space. Her forceful message is conveyed with historic images, supplemented by outstanding slides and short movies. This exceptional exhibition should appeal to a general audience and should also offer insights for anyone commissioning or designing a playground.

American playgrounds had a “golden moment” in the postwar period through the early 1970s. The “boomers,” who became school age and older during that time, were ready to be independent and active in public parks. In addition, people had more leisure time, and municipalities and foundations were willing to invest in public space in order to stem population shifts to suburbs and to lessen juvenile delinquency. At the same time, American artists led the worldwide art scene, and parks departments often welcomed their participation in projects. Architect Richard Dattner and landscape architect M. Paul Friedberg responded to these disparate strands by producing innovative playgrounds, largely in New York City.

Burkhalter has wisely highlighted Dattner (Figure 2) and Friedberg’s work in her narrative while also situating their designs within the context of the adventure playground movement. The postwar “adventure” or “junk” playgrounds of Scandinavia and Great Britain were sites where children could arrange and rearrange leftover scraps of building materials. The waste, which replaced traditional swings or seesaws, became known as “loose parts.” Burkhalter has appropriately re-created architect Dattner’s “loose parts”—colorful notched panels—from one of his 1960s playgrounds in Central Park. Her choice not only pays homage to the European postwar legacy and how it moved to the United States but also honors leaders of the movement. She provides extensive visual and textual information about them, including Danish landscape architect Carl Theodor Sørensen and British play advocate Lady Allen of Hurtwood. She supplements loose parts, which might still be able to transform playscapes today, by including a 1966 movie of an adventure playground in Denmark. It is a revelation to see its expansive space and multiage participants.

The enthusiasm for postwar playgrounds vaporized in America during the past four decades. There is no single reason for the decline. Federal guidelines, frivolous litigation, and general parental angst have all contributed to dull and expensive arrangements. Instead of loose parts and many opportunities for inventive play, we now typically have a hulking piece of mass-produced equipment. It directs how kids use it; it sits on a flat, inanimate safety surface; and it rests in a caged “island” that is meant to keep out adults without children more than to shelter little folks from traffic. Children quickly age out of these spaces, and the sites no longer have an ability to be a neighborhood retreat.

The contrast with historic projects in The Playground Project is immediately telling. Burkhalter cleverly paired her references to Aldo van Eyck and the small playgrounds he inserted seamlessly into Amsterdam with a movie from the Amsterdam City Archives that indicates how important these spaces were to the maturation of children in the 1950s. An urban planner (she also writes the intelligent blog Architektur für Kinder, Burkhalter researched and assembled the exhibition while she lived in Pittsburgh for eighteen months. During those months she uncovered forgotten European pieces that can now speak to our need to improve opportunities for children. Michael Grossert’s work is a good example. A movie (Figure 3) of his schoolyard at Reinach, Switzerland (1968), shows how children took advantage of a Brutalist concrete landscape that had endless opportunities for taking small, calculated risks, in addition to chances to play intensely together.

Burkhalter also examines the work of Palle Nielsen and the activities of Group Ludic. The former, a Danish artist, protested the blight of urban renewal of the 1960s by constructing adventure playgrounds that he called “guerilla playgrounds.” In 1968, the Stockholm Modern Museum invited him to take over a portion of the museum interior. The result was a well-known work (still being reproduced),

Modellen—A Model for a Qualitative Society. Burkhalter provides an excellent slide show that indicates how children at this site created fantastical spaces that beckoned all ages.

Group Ludic (architect Simon Koszel; fashion designer David Roditi; social scientist Xavier de la Salle) was another influential group, unknown in America. Formed in 1968 in Paris and disbanded by the 1990s, Group Ludic brought together random arrangements of abstract shapes. There were space-age spherical “eyeball” sculptures, too. All of these invited kids to act spontaneously; many of the pieces sat on the beach at holiday resorts and became social hubs.

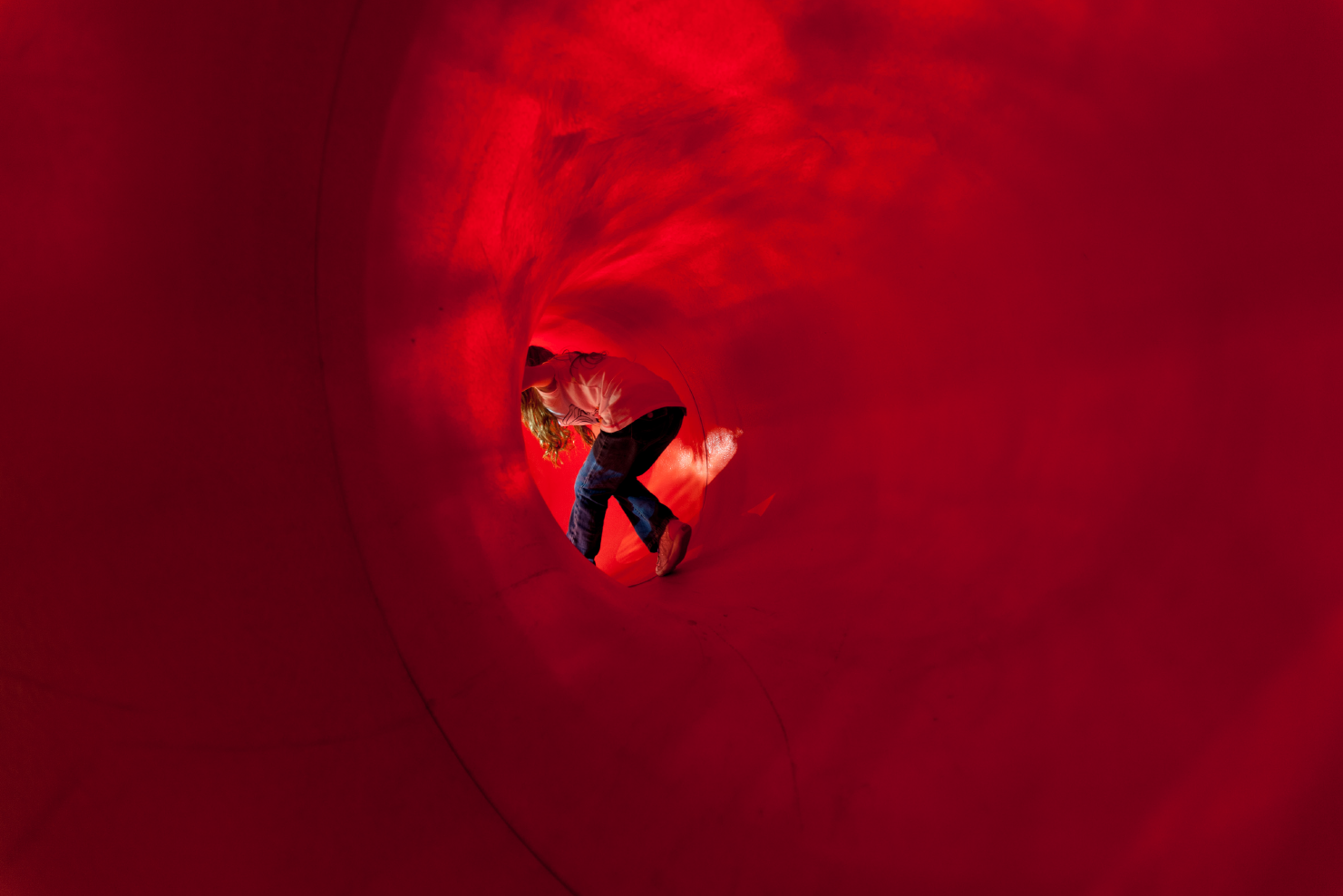

Even Burkhalter’s use of

Yvan Pestalozzi’s Lozziwurm (1972) is a critique of current playground practice (Figure 4). The piece, which sits at the entrance to the museum and is unfenced and readily accessible to a variety of age groups, invites children to crawl, hide, jump, and slither in impulsive ways (Figure 5). This temporary installation has a long history in her native Switzerland where it first appeared at Art Basel in the 1970s and later became a recreation staple of many shopping centers. Its very presence at the museum entrance tells us that public play spaces can be engaging, exciting, and a ready appendage to our normal streetscape.

Through terrific examples and supplemental movies, The Playground Project shows that artists of all stripes—architects, landscape architects, sculptors—helped invigorate playgrounds after World War II. The implication is that today’s practitioners could provide similar direction in early twenty-first century America. Let’s hope that this wonderful exhibition will travel to other venues and spread its powerful message.